X-Men

| X-Men | |

|---|---|

| File:X-Men174.jpg Cover to X-Men #174. Art by Salvador Larroca. | |

| Publication information | |

| Publisher | Marvel Comics |

| First appearance | (Uncanny) X-Men #1 (September 1963) |

| Created by | Stan Lee Jack Kirby |

| In-story information | |

| Base(s) | X-Mansion, or Xavier Institute for Higher Learning (formerly Xavier's School for Gifted Youngsters) |

The X-Men are one of the original group's of comic book superheroes featured in Marvel Comics. Created by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, they first appeared in X-Men #1 in September 1963, the same month as the debut of the Avengers.

X-Men has grown to become one of the most hugely popular franchises in the comic book industry, producing dozens of spin-off series and turning many of the writers and artists involved in the series into industry stars.

Since the early 1990s, the X-Men have been adapted into many other media, most notably two animated television series (X-Men and X-Men: Evolution) and a string of blockbuster Hollywood movies (X-Men, X2: X-Men United and X-Men 3).

The X-Men are mutants, human beings who, due to a quantum leap in evolution, are born with superhuman abilities. Mutants are often hated by regular humans both because of ordinary prejudice and because humans fear that mutants are destined to replace them. This fact is worsened by a number of mutants, most notably the team's arch-nemesis Magneto and Apocalypse, who use their powers to try to disrupt and dominate human society. The X-Men were gathered by the benevolent Professor X to protect a world that hates and fears them from Magneto and other threats.

The X-Men series is known for containing a richly diverse cast of characters and is perhaps the most multicultural book in comics.

The team's name is derived from the fact that mutants are extra-powered due to their similarly nominal x-factor gene, and was coined by Professor X.

History of the comics

The original X-Men

The first X-Men comic was created in September 1963 by writer Stan Lee and artist Jack Kirby.

In the comic book series, the X-Men were founded by the paraplegic telepath Professor Charles Xavier, alias Professor X. Xavier gathered the X-Men under the cover of a "School For Gifted Children" at a large country estate at 1407 Graymalkin Lane in Salem Center, a city in Westchester County, New York.

The original X-Men consisted of five teenagers still learning to control their powers, namely Cyclops (Scott Summers), Marvel Girl (Jean Grey), Angel (Warren Worthington), Beast (Hank McCoy) and Iceman (Bobby Drake). Early X-Men issues also introduced the team's archnemesis, Magneto and his Brotherhood of Evil Mutants.

In 1969, writer Roy Thomas and artist Neal Adams rejuvenated the franchise and introduced two new characters, Havok (Alex Summers) and Polaris (Lorna Dane). However, early X-Men issues failed to attract much critical acclaim and Marvel stopped producing new issues of X-Men in 1969. The series was still continued, reprinting earlier material in issue #67 - #93, and faded to near-obscurity.

The all-new, all-different X-Men

In 1975, writer Len Wein and artist Dave Cockrum introduced a new team of X-Men in Giant-Size X-Men #1 and this new team would appear in new issues of X-Men, beginning with issue #94. Rather than teenagers, this group consisted of adults who hailed from a variety of nations and cultures. The "all-new, all-different X-Men" were led by Cyclops from the original team, and consisted of Sunfire (Shiro Yashida), Thunderbird (John Proudstar), Banshee (Sean Cassidy), Colossus (Piotr Rasputin), Nightcrawler (Kurt Wagner), Storm (Ororo Munroe), and most notably, Wolverine (Logan).

The new issues of the series were illustrated by Dave Cockrum and later John Byrne, and written by Chris Claremont, who would go on to become the longest-standing contributor to the series. The run met great critical acclaim and produced the "Dark Phoenix Saga" and "Days of Future Past", arguably two of the greatest story arcs in Marvel Comics, as well as X-Men: God Loves, Man Kills, the base of the 2003 movie X2: X-Men United. Several new characters and teams were introduced, like Kitty Pryde, the Morlocks, the White Queen of the Hellfire Club, Rogue, Rachel Summers and Dazzler (Alison Blaire).

The series becomes a franchise

In the 1980s, the growing popularity of Uncanny X-Men and the rise of comic book specialty stores lead to the introduction of several spin-off series nicknamed "X-Books", most notably The New Mutants, X-Factor, Excalibur and others. This plethora of X-Men-related titles led to the rise of crossovers (sometimes called "X-Overs"), storylines which would overlap into several X-Books, sometimes for months at a time, such as Mutant Massacre.

Notable additions to the X-Men were Longshot, Jubilee (Jubilation Lee), Gambit (Remy LeBeau) and Psylocke (Betsy Braddock). A controversial move was to have Professor X relocate to space in 1986 and making Magneto the head of the X-Men. This period also included the arrival of the mysterious Madelyne Pryor and the return of Jean Grey.

Sales boom of the 1990s and artist exodus

In 1991, Marvel revised the entire lineup of X-books, creating X-Force, led by the mysterious warhawk Cable, written by Rob Liefeld, and launched a second X-Men series, simply called X-Men (the original series of this title having been already renamed to Uncanny X-Men), written by Claremont and illustrated by Jim Lee.

Internal friction split the X-Men books' creative teams. Claremont left after only three issues of X-Men due to clashes with Marvel editors and with Lee, ending his fifteen-year run as X-Men writer. Months later, Liefeld and Lee left Marvel with several other popular artists (including Marc Silvestri and Whilce Portacio) to form Image Comics.

Notable story arcs of this time are the "The X-Tinction Agenda" (1990), "X-Cutioner's Song" (1992), "Phalanx Covenant" (1994), "Legion Quest"/"Age of Apocalypse" (1995), "Onslaught" (1996) and "Operation: Zero Tolerance" (1997), in which an anti-mutant army is given license to hunt down the X-Teams and other mutants.

The 1990s saw an even greater number of X-books, with numerous ongoing series and miniseries running at any given time. Ongoing series from this time included Generation X, starring another team of teenage mutants and X-Man, starring a powerful young mutant (Nate Grey - an alternate version of Cable) from the "Age of Apocalypse" reality. Marvel launched solo series for several characters including Cable, Gambit, Bishop and Deadpool, a sarcastic mercenary antagonist of X-Force. In 1998 Excalibur and X-Factor ended and the latter was replaced with the parallel world series Mutant X starring Havok.

Changing and modernizing the franchise

Wandering plot lines and forgettable new villains plagued Claremont's return, leading Marvel's new Editor-in-Chief Joe Quesada to remove him from the two flagship titles in early 2001 and move him to a new spinoff series, X-Treme X-Men. At the same time, Marvel cancelled or overhauled many series and added new series like Weapon X, Exiles and the new X-Force (later retitled X-Statix). Many of these new comics were sarcastic, cynical, or deeply responsive to the established look of the superhero comic book, and were a distinct reaction to the increasingly predictable nature of Marvel comics in the 1990s.

The focus of 2001 was the ascent of writer Grant Morrison and artist Frank Quitely to X-Men, retitled New X-Men. Morrison's run was lauded as being both original and rejuvenating. The bright spandex costumes that had become iconic over the previous three decades were gone, replaced by black leather street clothes reminiscent of the dressed-down chic of the film The Matrix and the X-Men movies. In New X-Men, the Xavier Institute grew in size and scope, and introduced several powerful and memorable villains, most notably Cassandra Nova, Xavier's evil twin sister. During the Morrison run, Emma Frost went from vicious Hellfire Club dominatrix to icy member of the mutant squad, Xavier was publicly "outed" as a mutant, and the decades-long relationships of Jean Grey and Scott Summers and Lorna Dane and Alex Summers all disintegrated. In the meantime, Uncanny X-Men was written by Joe Casey, followed by Chuck Austen, only to mediocre acclaim.

Another popular new X-Men series was Ultimate X-Men, writer Mark Millar and artist Adam Kubert's reinvention of the concept featuring teenaged versions of the X-Men and meant to appeal to new readers. Ultimate X-Men was set in the Ultimate Marvel Universe, alongside Ultimate Spider-Man and Ultimates, a dark post-9/11 world that feared mutant terrorism and reflected the heightened militaristic climate of the Bush-era United States. Iconic characters were substantially overhauled and given new backgrounds, while meant to be refreshingly current for a new generation.

Post Morrison X-Men and House of M

In 2004, Morrison left New X-Men and Marvel prepared for what was already being called the "post-Morrison period". Marvel cancelled X-Treme X-Men and placed Claremont back on Uncanny X-Men. The company also launched Astonishing X-Men with writer Joss Whedon (well-known as the creator of the television series Buffy the Vampire Slayer) and artist John Cassaday (Planetary). With the departure of Morrison the X-Men franchise shifted yet again, attempting to incorporate some of the newer energy of the previous run with more traditional elements. Following the destruction of the mutant paradise of Genosha by the deadly sentinels under the influence of Cassandra Nova, Xavier left in order to restore a vague sense of order and stability to the wasted land (recounted in the short second series of Excalibur), leaving Cyclops and Emma Frost as the new leaders of the Institute, which now functions as a large-scale school. Jean Grey was killed off during Morrison's run, allowing the former White Queen and Scott Summers to pursue a relationship, a controversial move that both intrigued and alienated long-term fans.

Several short-lived spin-offs marked the 2004-2005, including books focusing on Gambit, Rogue, Bishop (in the mutant ghetto of District X), and Jubilee. New on-going series included New X-Men: Academy X, a teenaged soap opera comic focusing on the lives of the new young mutants at the Institute, and a relaunch of the Morrison-era New Mutants title.

The current period has been dominated by the reality-warping changes of the summer crossover event House of M, which has temporarily created a mutant paradise with Magneto as the world's dictator. It remains to be seen what will happen in the aftermath of House of M, or how the X-Men will respond.

Real-life comparison

The entire X-Men franchise is built on a sociopolitical undercurrent. Mutants are often seen as a metaphor for racial, religious and other minorities that face oppression - including, specifically, the struggle of African-Americans, discrimination against homosexuals, Anti-semitism, and the case of the Red Scare. Also, on an individual level, a number of X-Men serve a metaphorical function, as their powers illustrate points about the nature of the outsider.

Racism

Professor X has been compared to African American civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. and Magneto to the more militant Malcolm X. The X-Men’s purpose is sometimes referred to achieving "Xavier’s dream," perhaps a reference to King’s historic "I Have a Dream" speech.

Template:QuoteSidebar Also, X-Men comic books have often portrayed mutants as the victim of mob violence, evoking the lynchings of African-Americans in the age before the American civil rights movement.

While this interpretation has become commonplace, it is not without its critics. In 2002, comics critic Julian Darius argued in "X-Men is Not an Allegory of Racial Tolerance" that a close examination of early X-Men comics would make Magneto not Malcolm X but his group the violent Black Panthers. In the earliest comics, Xavier expressed no concern with mutant rights, instead focusing on stopping mutant menaces. He was, wrote Darius, explicitly counter-revolutionary.

Homosexuality

Another civil rights metaphor applied to the X-Men is that of gay rights. Comparisons have been made between the mutants' situation, including the concealment of their powers and the age they realize these powers, and homosexuality. This was illustrated in a scene of the second X-Men film (directed by openly gay director Bryan Singer) in which Bobby Drake "came out" as a mutant to his parents.

The comic books delved into the AIDS epidemic during the early 1990s with a long-running plotline about the Legacy Virus, a seemingly incurable disease, similarly thought at first to only attack mutants.

Anti-semitism

Somewhat more explicitly suggested is the comparison to anti-semitism. Magneto, a Holocaust survivor, sees the situation of mutants as similar to those of Jews in Nazi Germany. At one point he even utters the words "never again" in a 1992 episode of the X-Men animated series. In the comic books, Magneto has routinely sought to establish a "mutant homeland," which may be a parallel to modern day Israel. The mutant slave labor camps on the island of Genosha, in which numbers were burned into mutants’ foreheads, show much in common with Nazi concentration camps as do the internment camps of the classic Days of Future Past storyline.

"Red scare"

Occasionally, undercurrents of the "red scare" are present. Senator Robert Kelly's proposal of a "Mutant Registration Act" is similar to the efforts of Congress to effectively ban communism in the United States. In the 2000 X-Men film Kelly exclaims "we need to find out who these mutants are and what they can do." It should be noted, though, that issues of class stratification have never been part of the X-Men’s creed.

As a subculture

In some cases, particularly in Grant Morrison’s stories of the early 2000s, mutants were portrayed as a distinct subculture with “mutant bands” and a popular mutant fashion designer who created outfits tailored to mutant physiology. Also, the series District X takes place in an area of New York City called "mutant town." These instances can also serve as analogies for any minority within the population that establishes a specific subculture of its own.

Director Bryan Singer has remarked that aside from specific differences of race or sexual orientation, the X-Men has served as a metaphor for acceptance of all people for their special and unique gifts. The mutant "power" that must be hidden from the world is analogous to feelings of difference and fear usually developed in everyone during adolescence. Part of the attraction of the X-Men is that it offers a sanctuary to openly explore and celebrate your differences within a unique subculture.

Characters

This metaphorical content is also present, more personally rather than politically, in some of the characters. For instance, Cyclops must wear a visor or specialized glasses at all times to keep his powers in control and has thus grown-up emotionally restrained; Rogue, whose mutant power prevents her from establishing physical contact with others, feels an enormous sense of personal isolation and the scientifically brilliant Beast must always fight the perception that he is a monstrous brute due to his furry, animalistic appearance. Thus, the effects of alienation on one's well-being and psyche are often explored in the franchise.

Character diversity

Since Giant-Size X-Men #1 (1975), the X-Men have also become famous for their wide cultural and ethnic diversity.

International characters

Long before international characters became popular in the comics world, the X-Men franchise brought in characters from all over the world, such as from:

- Africa: Algeria (M), Egypt (Apocalypse), Kenya (Storm), South Africa (Maggott)

- Americas: Brazil (Sunspot), Cajun American (Gambit), Canada (Alpha Flight plus Wolverine, Sabretooth), Chinese American (Jubilee), First Nations (Shaman), Mexico (Rictor), indigenous America (Forge, Moonstar, Thunderbird I and Warpath), Puerto Rico (Cecilia Reyes), Quebec (Northstar and Aurora)

- Asia: Afghanistan (Dust and Sage), China (Xorn I and II,), India (Thunderbird III), Japan (Sunfire and Sunpyre, Silver Samurai, Shinobi Shaw), Vietnam (Karma)

- Europe: Austria (Mystique), England (Chamber, Psylocke, Captain Britain), France (Fantomex, although by choice), Germany (Nightcrawler and Maverick), Greece (Avalanche), Ireland (Banshee, Siryn, Black Tom Cassidy), Netherlands (Beak), Russia (Colossus, Omega Red, Darkstar, Magik, Soul Reaper), Scotland (Wolfsbane, Moira MacTaggert, Banshee, Siryn), Poland (Magneto)

- Middle East: Israel (Sabra)

- Oceania: Aborigine (Bishop, Shard, Gateway), Australia (Pyro)

Religious, sexual and other minorities

In addition, characters within the X-Men mythos also reflect religious, ethnic or sexual minorities. Examples of Jewish characters include Shadowcat, Magneto, and Sabra, whilst Dust has Muslim beliefs and Thunderbird III and Karima Shapandar are followers of the Hindu faith. In terms of sexuality, homosexual characters include Northstar, Destiny and Karma, with Mystique portrayed as being bisexual. The comics have also featured mutants whose mutation results in physical disfigurement as well as the granting of powers, with the Morlocks, inspired in part by the Morlock characters created by H.G. Wells, having portrayed to some degree the experience of disfigured people in late twentieth century American society.

Fictional places

The X-Men also introduced several fictional locations which are regarded as important within the shared universe in which Marvel Comics characters exist:

- Genosha, an African island near Madagascar and a long-time apartheid regime against mutants.

- Madripoor, an island in Southeast Asia, near Singapore. Associated with Viper.

- Muir Island, a Scottish island, commonly associated with being the place of Moira MacTaggert's laboratory.

- Savage Land, a hidden prehistoric location in Antarctica.

Appearances in other media

Animated television series

- In 1989, Marvel Entertainment produced a pilot for an X-Men series called Pryde of the X-Men, which only aired once, but was later released on video.

- In 1992, the Fox Network launched an unrelated X-Men animated series with the roster of Beast, Cyclops, Gambit, Jean Grey, Jubilee, Professor X, Rogue, Storm, and Wolverine, with Bishop and Cable frequently guesting. The series was an extraordinary success, becoming one of the most watched animated series in television history and helping widen the X-Men's popularity. It continued for five seasons, ending in 1997.

- In 2000, Warner Brothers Network launched X-Men: Evolution, which portrayed the X-Men as teenagers attending regular high school in addition to the Xavier Institute. The series ended in 2003 after its fourth season.

Feature films

The first attempts to make a film version of the X-Men began in the late 1980s along with Spider-Man and Hulk films. James Cameron, director of Aliens and The Terminator, was said to be the most likely director of the films, but it never came to fruition. In 1996, FOX produced a television movie based on the X-Men spinoff Generation X.

X-Men

In 2000, 20th Century Fox released X-Men, a $75 million film adaptation of the comic, directed by Bryan Singer. The film, along with the Blade series and Spider-Man, gathered approval from fans and enough good reviews to begin a revival of superhero-themed movies, such as Daredevil, Elektra, Hulk, and Fantastic Four.

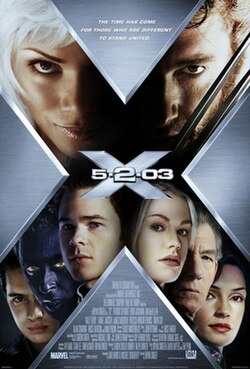

X2

In 2003, the sequel X2: X-Men United, also directed by Singer, was released. This film was loosely based on the 1982 graphic novel God Loves, Man Kills. It was an even greater success than the first movie, and many fans and critics considered it a superior film.

X-Men 3

As of 2005, a third movie, X-Men 3, is scheduled for release in 2006 and filming began in June 2005. Singer did not return for the third movie of the franchise, as he signed on to direct Superman Returns instead. Director Matthew Vaughn was slated to direct, but dropped out in June 2005 due to "personal issues". 20th Century Fox and Marvel Entertainment set Brett Ratner to replace Matthew Vaughn as the director of X-Men 3.

Cast

The line-up of all three X-Men films:

| Character | Actor(s) |

|---|---|

| The X-Men: | |

| Professor X (Charles Xavier) | Patrick Stewart |

| Cyclops (Scott Summers) | James Marsden |

| Storm (Ororo Munroe) | Halle Berry |

| Jean Grey | Famke Janssen |

| Wolverine (Logan) | Hugh Jackman |

| Nightcrawler (Kurt Wagner) | Alan Cumming |

| Beast (Dr. Hank McCoy) | Steve Bacic (in X2) Kelsey Grammer (in X-Men 3) |

| Younger students: | |

| Iceman (Bobby Drake) | Shawn Ashmore |

| Rogue (Marie D'Canto) | Anna Paquin |

| Colossus (Piotr Rasputin) | Daniel Cudmore |

| Shadowcat (Kitty Pride) | Sumela Kay (in X-Men) Katie Stuart (in X2) Ellen Page (in X-Men 3) |

| Jubilee (Jubilation Lee) | Katrina Florece (in X-Men) Kea Wong (in X2 and X-Men 3) |

| Angel (Warren Worthington III) | Ben Foster |

| Brotherhood members: | |

| Magneto (Erik Lensherr) | Ian McKellen |

| Mystique (Raven Darkholme) | Rebecca Romjin |

| Toad (Mortimer Toynbee) | Ray Park |

| Sabretooth (Victor Creed) | Tyler Mane |

| Pyro (John Allerdyce) | Aaron Stanford |

| Juggernaut (Cain Marko) | Vinnie Jones |

| Other villains: | |

| William Stryker | Brian Cox |

| Lady Deathstrike (Yuriko Oyama) | Kelly Hu |

| Other characters: | |

| Senator Kelly | Bruce Davison |

Spin-off movies

Lauren Donner, producer for the first two movies, has said the movie studio is interested in producing two spin-off films.

- One film will star Wolverine, in which Hugh Jackman will reprise his role as the clawed warrior.

- Screenwriter Sheldon Turner is currently working on bringing Magneto to the big screen in his own spin-off film. The plot will deal with the character's friendship turned sour with Charles Xavier. Turner has stated that "It's going to take place from 1939 Auschwitz up to 1955 or so,".

- Rebecca Romijn-Stamos, who plays Mystique in the X-Men franchise, has been approached about a Mystique film.

Reputable movie news site http://www.superherohype.com is now reporting that X-Men 3 screenwriter Zak Penn is now writing a third X-Men spin-off film as well.

Star Trek crossovers

In 1995, Pocket Books published Planet X, a novel that featured the X-Men sharing an adventure with the crew of the U.S.S. Enterprise from Star Trek: The Next Generation. (Ironically, the cover of this novel featured both Charles Xavier and Jean-Luc Picard. Picard was portrayed by Patrick Stewart, who would play the role of Xavier five years later in the feature X-Men film.) Similar crossovers occurred in comic book form, as Marvel had just launched a new series of Star Trek comic books. These crossovers were roundly criticized by fans of both franchises.

Controversy

The neutrality of this article is disputed. |

Some people feel that the premise of the X-Men is ridiculous and inconsistent. They feel that the mutants are just superheroes who are prejudiced with no reason except to try to give a politically correct message, even though they live in a world where many other people with superpowers (the Avengers, the Fantastic Four...) equal to them and yet are not subject to the same treatment. The mutants are, according to those detractors, very unlike minorites in the real-world who do not have superpowers or a normal physique.

See also

References

- Dussere, Erik The queer world of the X-Men Salon.com July 10 2000 Accessed on September 29 2005

- Fecteau, Lydia Mutant and Cyborg Images of the Disabled Body in the Landscape of Science Fiction 12 July 2004 available online as word document Accessed on September 29 2005

- Morrison, Grant The geek shall inherit the earth The Evening Standard August 10 2000 Accessed on September 29 2005

External links

- Official webpage at Marvel.com

- Chronology.Net (X-versum continuity and timelines)

- Children of The Atom (Information on the 1953 SF novel that was a precursor to the X-Men, and author Wilmar Shiras)

- GameFAQ's Comic Book FAQ: X-Men

- UncannyXmen.net

- DRG4's X-Men the Animated Series Page

- mutanthigh.com

- The X-Men Central