Conatus

Conatus, (Latin: an exertion, effort; an impulse, inclination; an undertaking),[1] is a term used in philosophy to refer to a few different theories on psychology and metaphysics.

Over time, the meaning and use of the term conatus has evolved, having been defined by Cicero, René Descartes, Thomas Hobbes and Baruch Spinoza.[2] This concept has been used to describe the tendency of objects to move. This tendency was associated with God by Descartes, then the motion of other bodies by Hobbes. Later, Spinoza took the term to explain the motion of humans and living beings and their will to live.[3] In all of these interpretations, conatus is associated with nature, and a body's inclination to follow what is natural or God's will.[2]

Conatus is also a term in early physics describing the property of inertia which was described in Newton's Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica of 1687. In 1677, with the publication of his Ethics, Spinoza almost predicts this theory: "By striving for motion we do not understand any thought, but only that a part of matter is so placed and stirred to motion, that it really would go somewhere if it were not prevented by any cause."[2]

History

Cicero

Cicero and contemporaries used the term conatus (and synonyms) to describe the forward-striving nature of human psychology. [2]

Descartes

Descartes described the concept of conatus, "to be an active power or tendency of bodies to move, expressing the power of God."[3] He spoke specifically of conatus a centro or conatus recedendi.

Conatus a centro, or "effort towards the center", Descartes used as a theory of gravity. Conatus recendendi, or "effort from the center" represented the centrifugal forces.[4]

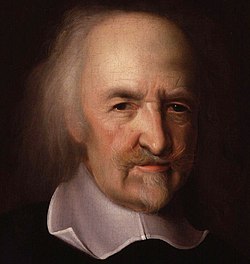

Hobbes

According to Thomas Hobbes, a physical body's conatus, or tendency to motion, "is determined by the motions of other bodies." Hobbe's uses the term mostly in the sense of "endeavors" or infinitesimal and presistent motion. This concept formed part of the basis for his political philosophy.[3]

Hobbes describes emotion as the impetus for motion and will as the sum of all emotions and the final balance of aversion and attraction. This will forms the conatus of a body. One important aspect of Hobbes' conatus is that it represents the will to survive. "A living being endeavors to preserve its life and resist anything contrary to it." [3] In order that living beings much accomplish this goal, Hobbes proffers, they seak peace and fight anything that threatens this peace.[3]

Spinoza

Psychological

Conatus is an important principal of Baruch Spinoza's philosophical on psychology which represents a being's will to survive. In part III of his Ethics, Spinoza asserts, "Each thing, as far as it can by its own power, strives to persevere in being". Spinoza used this concept to explain seemingly irregular human behavior as really "natural".[5][2]

It is similar to the libido model of Sigmund Freud. Spinoza's formulation of this concept, along with his rejection of free-will, was done as a response to his predecessors' non-naturalistic views.[2][5]

Physical

According to Spinoza, conatus is fundamental to existence of everything, even equal to, "the actual essence of the thing". For Spinoza's naturalism, Spinoza thinks, "that whatever is true about bodies is true about minds also"[2]

See also

References

- ^ Latin Dictionary

- ^ a b c d e f g Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- ^ a b c d e http://www.bu.edu/wcp/Papers/Mode/ModePiet.htm

- ^ HOW NEWTON FAILED TO DISCOVER THE LAW OF GRAVITY. Retrieved August 9, 2006.

- ^ a b The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy