Parallax Propeller

The Parallax P8X32A Propeller is a multi-core processor parallel computer architecture microcontroller chip with eight 32-bit reduced instruction set computer (RISC) central processing unit (CPU) cores.[1][2] Introduced in 2006, it is designed and sold by Parallax, Inc.

The Propeller microcontroller, Propeller assembly language, and Spin interpreter were designed by Parallax's cofounder and president, Chip Gracey. The Spin programming language and Propeller Tool integrated development environment (IDE) were designed by Chip Gracey and Parallax's software engineer Jeff Martin.

On August 6, 2014, Parallax Inc. released all of the Propeller 1 P8X32A hardware and tools as open-source hardware and software under the GNU General Public License (GPL) 3.0. This included the Verilog code, top-level hardware description language (HDL) files, Spin interpreter, PropellerIDE and SimpleIDE programming tools and compilers.[3]

In 2020, the Parallax Propeller 2 (P2X8C4M64P) was released.

Multi-core architecture

[edit]Each of the eight 32-bit cores (termed a cog) has a central processing unit (CPU) which has access to 512 32-bit long words (2 KB) of instructions and data. Self-modifying code is possible and is used internally, for example, as the boot loader overwrites itself with the Spin Interpreter. Subroutines in Spin (object-based high-level code) use a call-return mechanism requiring use of a call stack. Assembly (PASM, low-level) code needs no call stack. Access to shared memory (32 KB random-access memory (RAM); 32 KB read-only memory (ROM)) is controlled via round-robin scheduling by an internal computer bus controller termed the hub. Each cog also has access to two dedicated hardware counters and a special video generator for use in generating timing signals for PAL, NTSC, VGA, servomechanism-control, and others.[4]

Speed and power management

[edit]The Propeller can be clocked using either an internal, on-chip oscillator (providing a lower total part count, but sacrificing some accuracy and thermal stability) or an external crystal oscillator or ceramic resonator (providing higher maximum speed with greater accuracy at higher total cost). Only the external oscillator may be run through an on-chip phase-locked loop (PLL) clock multiplier, which may be set at 1x, 2x, 4x, 8x, or 16x.

Both the on-board oscillator frequency (if used) and the PLL multiplier value may be changed at run-time. If used correctly, this can improve power efficiency; for example, the PLL multiplier can be decreased before a long no operation wait needed for timing purposes, then increased afterward, causing the processor to use less power. However, the utility of this technique is limited to situations where no other cog is executing timing-dependent code (or is carefully designed to cope with the change), since the effective clock rate is common to all cogs.

The effective clock rate ranges from 32 kHz up to 80 MHz (with the exact values available for dynamic control dependent on the configuration used, as described above). When running at 80 MHz, the proprietary interpreted Spin programming language executes approximately 80,000 instruction-tokens per second on each core, giving 8 times 80,000 for 640,000 high-level instructions per second. Most machine-language instructions take 4 clock-cycles to execute, resulting in 20 million instructions per second (MIPS) per cog, or 160 MIPS total for an 8-cog Propeller.

Power use can be reduced by lowering the clock rate to what is needed, by turning off unneeded cogs (which then use little power), and by reconfiguring I/O pins which are unneeded, or can be safely placed in a high-impedance state (tristated), as inputs. Pins can be reconfigured dynamically, but again, the change applies to all cogs, so synchronizing is important for certain designs. Some protection is available for situations where one core attempts to use a pin as an output while another attempts to use it as an input; this is explained in Parallax's technical reference manual.

On-board peripherals

[edit]Each cog has access to some dedicated counter-timer hardware, and a special timing signal generator intended to simplify the design of video output stages, such as composite PAL or NTSC displays (including modulation for broadcast) and Video Graphics Array (VGA) monitors. Parallax thus makes sample code available which can generate video signals (text and somewhat low-resolution graphics) using a minimum parts count consisting of the Propeller, a crystal oscillator, and a few resistors to form a crude digital-to-analog converter (DAC). The frequency of the oscillator is important, as the correction ability of the video timing hardware is limited to the clock rate. It is possible to use multiple cogs in parallel to generate a single video signal. More generally, the timing hardware can be used to implement various pulse-width modulation (PWM) timing signals.

ROM extensions

[edit]In addition to the Spin interpreter and a boot loader, the built-in ROM provides some data which may be useful for certain sound, video, or mathematics applications:

- a bitmap font is provided, suitable for typical character generation applications (but not customizable);

- a logarithm table (base 2, 2048 entries);

- an antilog table (base 2, 2048 entries); and

- a sine table (16-bit, 2049 entries representing first quadrant, angles from 0 to π/2; other three quadrants are created from the same table).

The math extensions are intended to help compensate for the lack of a floating-point unit, and more primitive missing operations, such as multiplication and division (this is masked in Spin but is a limit for assembly language routines). The Propeller is a 32-bit processor, however, and these tables may have insufficient accuracy for higher-precision uses.

Built in Spin bytecode interpreter

[edit]Spin is a multitasking high-level computer programming language created by Parallax's Chip Gracey, who also designed the Propeller microcontroller on which it runs, for their line of Propeller microcontrollers.[5]

Spin code is written on the Propeller Tool, a GUI-oriented software development platform written for Windows XP.[6] This compiler converts the Spin code into bytecodes that can be loaded (with the same tool) into the main 32 KB RAM, and optionally into the I²C boot electrically erasable programmable read-only memory (EEPROM), of the Propeller chip. After booting the propeller, a bytecode interpreter is copied from the built in ROM into the 2 KB RAM of the primary COG. This COG will then start interpreting the bytecodes in the main 32 KB RAM. More than one copy of the bytecode interpreter can run in other COGs, so several Spin code threads can run simultaneously. Within a Spin code program, assembly code program(s) can be inline inserted. These assembler program(s) will then run on their own COGs.

Like Python, Spin uses indentation whitespace, rather than curly braces or keywords, to delimit blocks.

The Propeller's interpreter for its proprietary multi-threaded Spin computer language is a bytecode interpreter. This interpreter decodes strings of instructions, one instruction per byte, from user code which has been edited, compiled, and loaded onto the Propeller from within a purpose-specific integrated development environment (IDE). This IDE, which Parallax names The Propeller tool, is intended for use under a Microsoft Windows operating system.

The Spin language is a high-level programming language. Because it is interpreted in software, it runs slower than pure Propeller assembly, but can be more space-efficient: Propeller assembly opcodes are 32 bits long; Spin directives are 8 bits long, which may be followed by a number of 8-bit bytes to specify how that directive operates.

At startup, a copy of the bytecode interpreter (less than 2 KB in size), will be copied into the dedicated RAM of a cog and will then start interpreting bytecode in the main 32 KB RAM. Additional cogs can be started from that point, loading a separate copy of the interpreter into the new cog's dedicated RAM (a total of eight interpreter threads can, thus, run simultaneously). Notably, this means that at least a minimal amount of startup code must be Spin code, for all Propeller applications.

Syntax

[edit]Spin's syntax can be divided into blocks, which hold:

- VAR – global variables

- CON – program constants

- PUB – code for a public subroutine

- PRI – code for a private subroutine

- OBJ – code for objects

- DAT – predefined data, memory reservations and assembly code

Example keywords

[edit]- reboot: causes the microcontroller to reboot

- waitcnt: wait for the system counter to equal or exceed a specified value

- waitvid: waits for a (video) timing event before outputting (video) data to I/O pins

- coginit: starts a processor on a new task

Example program

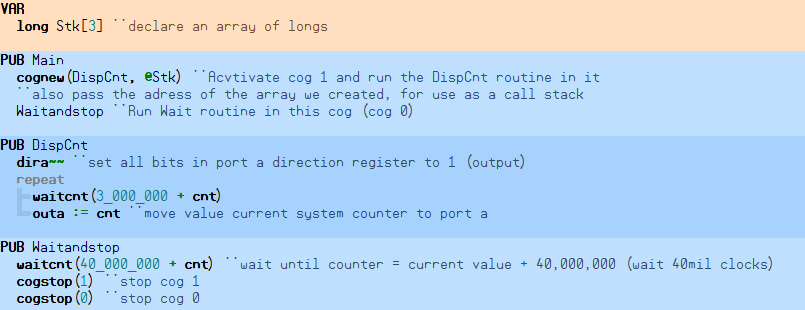

[edit]An example program, (as it would appear in the Propeller Tool editor) which emits the current system counter every 3,000,000 cycles, then is shut down by another cog after 40,000,000 cycles:

Package and I/O

[edit]The initial version of the chip (called the P8X32A) provides one 32-bit port in a 40-pin 0.6 in dual in-line package (DIP), 44-pin LQFP, or Quad Flat No-leads package (QFN) surface-mount technology package. Of the 40 available pins, 32 are used for I/O, four for power and ground pins, two for an external crystal (if used), one to enable power outage and brownout detection, and one for reset.

All eight cores can access the 32-bit port (designated "A"; there is currently no "B") simultaneously. A special control mechanism is used to avoid I/O conflicts if one core attempts to use an I/O pin as an output while another tries to use it as input. Any of these pins can be used for the timing or pulse-width modulation output techniques described above.

Parallax has stated that it expects later versions of the Propeller to offer more I/O pins and/or more memory.[7]

Virtual I/O devices

[edit]

The Propeller's designers designed it around the concept of "virtual I/O devices". For example, the HYDRA Game Development Kit, (a computer system designed for hobbyists, to learn to develop retro-style video games) uses the built-in character generator and video support logic to generate a virtual graphics processing unit-generator that outputs VGA color pictures, PAL/NTSC compatible color pictures or broadcast RF video+audio in software.[8]

The screen capture displayed here was made using a software virtual display driver that sends the pixel data over a serial link to a PC.[9]

Software libraries are available to implement several I/O devices ranging from simple UARTs and Serial I/O interfaces such as SPI, I²C and PS/2 compatible serial mouse and keyboard interfaces, motor drivers for robotic systems, MIDI interfaces and LCD controllers.[10]

Dedicated cores instead of interrupts

[edit]The design philosophy of the Propeller is that a hard real-time multi-core architecture negates the need for dedicated interrupt hardware and support in assembly. In traditional CPU architecture, external interrupt lines are fed to an on-chip interrupt controller and are serviced by one or more interrupt service routines. When an interrupt occurs, the interrupt controller suspends normal CPU processing and saves internal state (typically on the stack), then vectors to the designated interrupt service routine. After handling the interrupt, the service routine executes a return from interrupt instruction which restores the internal state and resumes CPU processing.

To handle an external signal promptly on the Propeller, any one of the 32 I/O lines is configured as an input. A cog is then configured to wait for a transition (either positive or negative edge) on that input using one of the two counter circuits available to each cog. While waiting for the signal, the cog operates in low-power mode, essentially sleeping. Extending this technique, a Propeller can be set up to respond to eight independent interrupt lines with essentially zero handling delay. Alternately, one line can be used to signal the interrupt, and then additional input lines can be read to determine the nature of the event. The code running in the other cores is not affected by the interrupt handling cog. Unlike a traditional multitasking single-processor interrupt architecture, the signal response timing remains predictable,[11] and indeed using the term interrupt in this context can cause confusion, since this function can be more properly thought of as polling with a zero loop time.

Boot mechanism

[edit]On power up, Brownout detection, software reset, or external hardware reset, the Propeller will load a machine-code booting routine from the internal ROM into the RAM of its first (primary) cog and execute it. This code emulates an I²C interface in software, temporarily using two I/O pins for the needed serial clock and data signals to load user code from an external I2C EEPROM.

Simultaneously, it emulates a serial port, using two other I/O pins that can be used to upload software directly to RAM (and optionally to the external EEPROM). If the Propeller sees no commands from the serial port, it loads the user program (the entry code of which must be written in Spin, as described above) from the serial EEPROM into the main 32 KB RAM. After that, it loads the Spin interpreter from its built-in ROM into the dedicated RAM of its first cog, overwriting most of the bootloader.

Regardless of how the user program is loaded, execution starts by interpreting initial user bytecode with the Spin interpreter running in the primary cog. After this initial Spin code runs, the application can turn on any unused cog to start a new thread, and/or start assembly language routines.

External persistent memory

[edit]The Propeller boots from an external serial EEPROM; once the boot sequence completes, this device may be accessed as an external peripheral.[12]

Other language implementations

[edit]Apart from Spin and the Propeller's low-level assembler, a number of other languages have been ported to it.

C compiler

[edit]Parallax supports Propeller-GCC which is a port of the GNU Compiler Collection (GCC) compiler for the programming languages C and C++, for Propeller[13] (branch release_1_0). The C compiler and the C Library are ANSI C compliant. The C++ compiler is ANSI-C99 compliant. Full C++ is supported with external memory. The SimpleIDE program[14] provides users a simple way to write programs without requiring makefiles. In 2013, Parallax incorporated Propeller-GCC and Simple Libraries into the Propeller-C Learn series of tutorials.[15] Propeller-GCC is actively maintained. Propeller-GCC and SimpleIDE are officially supported Parallax software products.

The ImageCraft ICCV7 for Propeller C compiler has been marked to end-of-life state.[16]

A free ANSI C compiler named Catalina is available.[17] It is based on LCC. Catalina is actively maintained.

BASIC compiler

[edit]PropBASIC is a BASIC programming language for the Parallax Propeller Microcontroller.[18] PropBASIC requires Brad's Spin Tool (BST), a cross-platform set of tools for developing with the Parallax Propeller. As of August 2015, BST runs on i386-linux-gtk2, PowerPC-darwin (Mac OS X 10.4 through 10.6), i386-darwin (Mac OS X 10.4 through 10.6) and i386-Win32 (Windows 95 through Windows 7).

Forth on the Propeller

[edit]There are at least six different versions of Forth, both commercial and open-source software, available for the Propeller.

PropForth

[edit]A free version that enjoys extensive development and community support is PropForth.[19] It is tailored to the prop architecture, and necessarily deviates from any general standard regarding architectural uniqueness, consistent with the concept of Forth.

Beyond the Forth interpreter, PropForth provides many features that exploit the chip's abilities. Linked I/O refers to the method of associating a stream with process, allowing one process to link to the next on the fly, transparent to the application. This can reduce or eliminate the need of a hardware debugging or JTAG interface in many cases. Multi-Channel Synchronous Serial (MCS) refers to the synchronous serial communication between prop chips. 96-bit packets are sent continuously between two cogs, the result is that applications see additional resources (+6 cogs for each prop chip added) with little or no impact on throughput for a well constructed application.

LogicAnalyzer refers to an extension package that implements software logic analyzer. EEPROMfilesystem and SDfilesystem are extensions that implement rudimentary storage using EEPROM and SD flash.

PagedAssembler refers to the package of optimizations that allow assembler routines to be swapped in (and out by overwrite) on the fly, allowing virtually unlimited application size. Script execution allows extensions to be loaded on the fly, allowing program source up to the size of storage media.

Propeller and Java

[edit]There are efforts underway to run the Java virtual machine (JVM) on Propeller. A compiler, debugger, and emulator are being developed.[20]

Pascal compiler and runtime

[edit]A large subset of Pascal is implemented by a compiler and interpreter based on the p-code machine P4 system.[21]

Graphical programming

[edit]

PICo programmable logic controller (PLC, PICoPLC) supports output to Propeller processor. The program is created in a GUI ladder logic editor and resulting code is emitted as Spin source. PICoPLC also supports P8X32 with create-simulate-run feature. No restrictions on target hardware as the oscillator frequency and IO pins are freely configurable in the ladder editor. PICoPLC developer website ([1]).

Future versions

[edit]As of 2014[update], Parallax is building a new Propeller[22] with cogs that each will run at about 200 MIPS, whereas the current Propeller's cogs each run at around 20 MIPS. The improved performance would result from a maximum clock speed increase to 200 MHz (from 80 MHz) and an architecture that pipelines instructions, executing an average of nearly one instruction per clock cycle (approximately a ten-fold increase).[7]

References

[edit]- ^ Torrone, Phillip (February 18, 2006). "First look at Parallax's Propeller chip". Make blog. Archived from the original on 2008-06-25.

- ^ Torrone, Phillip (August 21, 2006). "Parallax Propeller (review)". Make.

- ^ Gracey, Ken (2014). "Propeller 1 Open Source". Parallax Inc. Parallax Inc. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

The Propeller 1 (P8X32A) is now a 100% open multicore microcontroller, including all of the hardware and tools ... The Propeller 1 may be the most open chip in its class.

- ^ Wong, William G. (December 15, 2022). "EiED Online>> Parallax Propeller".

- ^ Scanlan, David A.; Hebel, Martin A. (October 2007). "Programming the eight-core propeller chip". Journal of Computing Sciences in Colleges. 23 (1): 162–168.

- ^ "Prop Tool". Propeller wiki at Wikispaces. Archived from the original on 2008-10-01.

- ^ a b "Parallax Forums message". Parallax Forums.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Propeller Video Application Board PCB". SelmaWare Solutions. Archived from the original on 2008-12-21.; a dedicated video generator board with a propeller

- ^ "Parallax Forums post about screen capture software". Parallax Forums. Archived from the original on 2012-07-09.

- ^ p1 on GitHub; Propeller object exchange software library

- ^ "Interrupts". Propeller wiki at Wikispaces. Archived from the original on 2010-09-21.

- ^ Cantrell, Tom (August 2006). "Turning the Core-ner". Circuit Cellar. No. 193. p. 80. Archived from the original on 2007-06-28.

- ^ "PropGCC on Google Code".

- ^ "Propeller C - Set Up SimpleIDE". learn.parallax.com.

- ^ "Propeller C". learn.parllax.com.

- ^ "ICCV7 for Propeller (Non-Commercial) - End of Life". Parallax Inc. Archived from the original on 2011-09-18.

- ^ "Catalina - a FREE C compiler for the Propeller - The Final Frontier!". Parallax Forums. Archived from the original on 2012-07-31.

- ^ "Download PropBASIC here... 00.01.14 LAST VERSION FOR BST". Parallax Forums. 2009-12-23.

- ^ "propforth". code.google.com.

- ^ "Programming in Java". Propeller wiki at Wikispaces. Archived from the original on 2008-10-04.

- ^ "Programming in Pascal". Propeller wiki at Wikispaces. Archived from the original on 2008-10-04.

- ^ "Propeller 2". Parallax Inc. 23 July 2020.

External links

[edit]- Official website, Parallax Inc:

- Wiki with detailed information about the propeller

- Propeller forum at Parallax Inc:

- Propeller GCC Beta Site

- Article at EiED online

- a second article at EiED online

- An article at ferret.com.au

- List of programming languages running on the Propeller

- Download PICoPLC from APStech[permanent dead link]

- FirstSpin, a weekly educational audio program about the Spin programming language and the Propeller, sponsored by Parallax