Moa

- For the extinct ducks from Hawaii, see Moa-nalos.

- For the unit of angular measurement abbreviated MOA, see Minute_of_Arc.

| Moa | |

|---|---|

| |

| Moa attacked by Haast's eagle | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Superorder: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | Dinornithidae

|

| Genera | |

|

Anomalopteryx (bush moa) | |

Moa were giant flightless birds native to New Zealand. Ten species of varying sizes are known, with the largest species, the Giant Moa (Dinornis robustus and Dinornis novaezelandiae), reaching about 3 m (10 ft) in height and about 250 kg (550 lb) in weight. They were the dominant herbivores in the New Zealand forest ecosystem.

History

Moa are thought to have become extinct about 1500, although some reports speculate that a few stragglers may have persisted in remote corners of New Zealand until the 18th and even 19th Centuries.

Although it used to be thought that numbers were declining before the impact of humans, their extinction is now attributed to hunting and forest clearance by the Polynesian ancestors of the Māori, who settled in New Zealand a few hundred years earlier. Before the arrival of humans, moa were hunted by Harpagornis, the world's largest eagle, which is also now extinct. The kiwi was once regarded as a close relative of the Moa, but comparisons of their DNA suggest it is more closely related to the Australian emu and cassowary. (Turvey S. T. et al., letter in Nature. Vol. 435 No. 16 June 2005. Page 942)

Although the indigenous Māori told European settlers tales about the huge birds which they called Moa, which had once roamed the flats and valleys, the widespread physical evidence that they had actually existed was never closely examined by early European settlers.

|

In 1839, John W. Harris, a Poverty Bay flax trader who was a natural history enthusiast, was given a piece of unusual bone by a Māori who had found it in a river bank. He showed the 15cm fragment of bone to his uncle, John Rule, a Sydney surgeon, who sent it to Richard Owen who at that time was working at the Hunterian Museum at the Royal College of Surgeons in London. Owen became a noted biologist, anatomist and paleontologist at the British Museum.

Owen puzzled over the fragment for almost four years. He established it was part of the femur of a big animal, but it was uncharacteristically light and honeycombed.

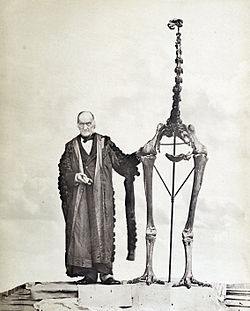

Owen announced to a skeptical scientific community and the world that it was from a giant extinct bird like an ostrich, and named it "Dinornis". His deduction was ridiculed in some quarters but was proved correct with the subsequent discoveries of considerable quantities of moa bones throughout the land, sufficient to construct skeletons of the birds.

Although dozens of species were described in the late 19th and early 20th century, many were based on partial skeletons and turned out to be synonyms. More recent research, based on DNA recovered from museum collections, suggest that there were only ten species, including two giant moa. The giant moa seems to have had sexual dimorphism, with females being much larger than males; so much bigger that they were formerly classified as separate species. The Giant Moa grew as large as 13 feet and became extinct much earlier (also by Māori hunting), about 1300.

In July 2004, the Natural History Museum in London placed on display the moa bone fragment Owen had first examined, to celebrate 200 years since his birth, and in memory of Owen as founder of the museum.

Claims by cryptozoologists

Though there is no reasonable doubt that the Moa is extinct, there has been occasional speculation that some may still exist in deepest south Westland, a rugged wilderness in the South Island of New Zealand. Cryptozoologists and others reputedly continue to search for them, but no hard evidence or actual specimens have ever been found, and their efforts are widely considered to be pseudoscientific.

In January 1993, on the West Coast, Paddy Freaney, Sam Waby and Rochelle Rafferty claimed to have seen a large Moa-like bird. Analysis of the blurry photograph they claimed was of a Moa suggested that the subject could be either a large bird or a red deer. The incident is considered a hoax, especially as Freaney is a hotelier, and may have concocted the story to attract tourists.

Moa experts say the likelihood of any Moa remaining alive is extremely unlikely, since they would be giant birds in a region often visited by hunters and hikers. Freaney cites the rediscovery of the takahe as evidence that living birds could still exist undiscovered. However, while the hen-sized takahe could successfully avoid humans, a large moa would have considerably more difficulty in doing so. The takahe was rediscovered after its tracks were identified, but no reliable evidence of Moa tracks has been reported.

References

- Millener, P. R. 1982. And then there were twelve: the taxonomic status of Anomalopteryx oweni (Aves: Dinornithidae). Notornis 29: 165-170.

See also

- List of extinct New Zealand animals (birds)

- Moa-nalos, a big extinct bird from Hawaii.