Ann Macbeth

Ann Macbeth | |

|---|---|

c. 1900, Macbeth is wearing a self-made collar embroidered with the Glasgow rose.[1] | |

| Born | Annie Macbeth 25 September 1875 Bolton, Lancashire, England |

| Died | 23 March 1948 (aged 72) Carlisle, Cumberland, England |

| Known for | Embroidery |

| Movement | Glasgow Movement, Arts and Crafts movement |

Ann Macbeth (25 September 1875 – 23 March 1948) was a British embroiderer, designer, teacher and author. She was a member of the Glasgow Movement where she was an associate of Margaret MacDonald and Charles Rennie Mackintosh, and many other 'Glasgow Girls'. She was also an active suffragette and designed banners for organisations supporting women’s suffrage, such as the Women’s Social and Political Union

Early life

[edit]Macbeth was born in the Bolton suburb of Halliwell, and studied at the Glasgow School of Art.[2] When Macbeth was a child, she had a scarlet fever attack. She was the eldest of nine children. Her father was Norman Macbeth, a mechanical engineer, and her mother was Annie MacNicol.[3]

She came from an artistic background: her uncles included the artists Robert Walker Macbeth and Henry Macbeth-Raeburn and her paternal grandfather was the portraitist Norman Macbeth. In 1902, she participated in the 'Scottish Section' of the First International Exhibition of Modern Decorative Art in Turin[4] where she won a silver medal for the design of the Glasgow Coat of Arms on one side of the banner presented to Professor Rucker of the British Association for the Advancement of Science.[5]

Teaching

[edit]

After completing her studies at the Glasgow School of Art in 1901 Macbeth became assistant to Jessie Newbery and her striking embroidery work was given regular coverage in The Studio. In 1906 she started teaching metalwork at the Glasgow School of Art. There she also taught bookbinding from 1907 to 1911, and ceramic decoration from 1912 onwards.[6]

From roughly 1902 to 1911, the needlework department was the largest of the craft sections at the Glasgow School of Art. There was a requirement that all Glasgow schoolgirls should be taught to sew. Work constructed by Newberry, Macbeth, and their students was of two main types: the bold, appliquéd, patterned style inspired by nature and found on practical items, or the more conventional aesthetic consisting of picture panels, which were found on fire screens or ecclesiastical hangings. Newberry might have been the bolder of the two designers, although Macbeth embroidered panels more extensively with expressive stitching. These embroidered panels featured young girls with garlands or girls set within a landscape, similar to the stained glass pieces of the period.[7]

In 1908 she succeeded Jessie Newbery as Head of the Needlework and Embroidery section at the Glasgow School of Art, and in 1912 she became the Director of Studies in the Needlework-Decorative Arts Studio.[8][9] In 1911 she took part in the planning for the Scottish Exhibition of National History, Art and Industry, sitting on the committee of the Decorative and Fine Arts Section.[10]

Together with the educational psychologist Margaret Swanson Macbeth published the textbook Educational Needlecraft in 1911. The textbook won international acclaim and widely influenced the teaching of needlecraft.[6] It remained on the Scottish school syllabus until the 1950s.[11] The embroidery classes at the Glasgow School of Art were open to the community as a whole. Saturday classes for schoolteachers led to a certificate by the Scottish Education Department. In her teaching and publications Macbeth spread the radical approach to design of the Glasgow Movement and put into practice the ideas of the Arts and Crafts movement. She elevated the status of home dressmaking and encouraged women to create their own individualistic clothing. She brought designed dresses within reach of women with modest means by advocating the use of "humble materials" such as cotton, linen and crash. In her publications Macbeth encouraged a new generation of designer-craftswomen, discouraging copying of patterns.[1]

The use of these humble materials separated her from artisans of the Morris circle, who used rich silks.[7] Macbeth considered the silks and satins most popular with the previous generation of art-embroiderers to not only be more costly, but ‘really less artistic’.[12]

From 1920 onwards Macbeth also taught handicrafts at the Women's Institute and participated in programmes to alleviate local economic hardship.[6] In her book Embroidered and Laced Leatherwork Macbeth lamented that women produced crafts in their spare time and devalued their work by undercharging for it so that barely the cost of the materials was covered. Through her teaching work at the Women's Institute Macbeth aimed to generate a means of livelihood for craftworkers by creating regional styles of work.[13]

Women's suffrage activism

[edit]Macbeth designed the banner for the 1908 Edinburgh march of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies.[14] In October 1909 the Glasgow branch of the Women's Social and Political Union, the militant wing of the campaign for women's suffrage in the United Kingdom, was presented with an embroidered banner designed by Macbeth.[15] For a 1910 exhibition Macbeth designed the WSPU Holloway Prisoners Banner a linen quilt with the embroidered signatures of the 80 suffragette hunger strikers. It was subsequently used as a banner.[16] Aside from working as a suffrage banner maker Macbeth was also a member of the Women's Social and Political Union[17] and she engaged in militant action. As a result, she was imprisoned although, as she does not appear in court or newspaper reports, she appears to have done so under a false name; the nature of her action is unknown. In a letter to the Secretary of the Glasgow School of Arts from May 1912 Macbeth thanked him for his "kind letters" and wrote "I am still very much less vigorous than I anticipated... after a fortnight's solitary imprisonment with forcible feedings". After the 1912 prison stay she needed several months care as a "semi-invalid".[18]

The School's Governors were extremely supportive of Macbeth during her time of recovery. Macbeth was given “every consideration until well enough to return to work.” This level of commitment highlighted a tacit approbation of artists advocating for the suffrage cause from the School's Governors.[19]

Artistic output

[edit]

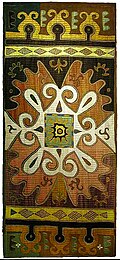

Macbeth became a renowned embroider and designer. Her prolific output included bookbindings, metalwork and designs for carpet manufacturers Alexander Morton and Co., Donald Bros. of Dundee, and Liberty's & Knox's Linen Thread Company.[16] For Liberty, Macbeth also provided Art Nouveau-style embroidery designs that featured in the firm's mail order catalogues until the outbreak of the First World War. Her designs were sold by Liberty as iron-on transfers for the embroidery of dresses and furniture.[20]

In 1920 Macbeth moved to Patterdale in Westmorland, Cumbria. She remained a visiting lecturer at the Glasgow School of Arts until her retirement in 1928. In Patterdale she continued to produce needleworks, often large decorative designs, and produced church hangings and vestments.[13] She also decorated china and fired her own china in a kiln she had built herself.[21] She devised a simple method of rug-weaving which was published in her book Country Woman’s Rug in 1929. She argued that machines would democratise design and that craftworkers who understood the workings of machines could achieve high artistic quality.[13] In the summers Macbeth lived on a crag in Helvelly in a self-designed house and captured the local hillsides in embroidery. Outside the house she dyed her own yarn in pits.[13]

Publicly accessible works

[edit]

St. Patrick's Church in Patterdale, Cumbria houses some of her embroideries. Examples of her work were on exhibition at Miss Cranston's tea-rooms in Glasgow over a long period. She designed and embroidered a frontal for the communion table of Glasgow Cathedral.[22]

A range of her work, both in embroidery and in ceramics, was on display in Kelvingrove Museum in its exhibition Making the Glasgow Style from 30 March to 14 August 2018.[23]

The Studio contains many images of her work.[24]

Publications

[edit]Macbeth published six books on embroidery: Educational Needlecraft[25] (first published in 1911, with Margaret Swanson), The Playwork Book (first published 1918), School and Fireside Crafts[26] (first published 1920 with May Spence), The Country Woman's Rug Book[27] (first published 1921), Needleweaving (first published 1922), and Embroidered Lace and Leatherwork[28] (first published 1924). She also produced several designs for jewellery some of which appear as illustrations in books by Peter Wylie Davidson.[29]

-

Embroidered and Laced Leatherwork by Macbeth

-

School and Fireside Crafts by Ann Macbeth and May Spence

References

[edit]- ^ a b Juliet Ash, Elizabeth Wilson (1990). Chic Thrills: A Fashion Reader. Edinburgh: Canongate. pp. 215–217. ISBN 1-84195-151-X.

- ^ Cunningham, Jennifer (21 June 2007). "How Scotland forged itself a bold and beautiful future A new exhibition celebrates the Arts and Crafts movement . . . and how it empowered women". The Herald. Archived from the original on 12 August 2016. Retrieved 9 February 2012.

- ^ "Saints in the Oxford DNB". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. 23 September 2004. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/92873. ISBN 978-0-19-861412-8. Retrieved 20 November 2020. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ "Mackintosh Architecture: The Catalogue - browse - display". www.mackintosh-architecture.gla.ac.uk. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- ^ Arthur, Liz (1990). Ann Macbeth (1875–1948), pp. 153–55, Glasgow Girls. Women in Art and Design, 1880-1920. (Ed. Jude Burkhauser). Edinburgh: Canongate. p. 153. ISBN 1-84195-151-X.

- ^ a b c Elizabeth L. Ewan; Sue Innes; Sian Reynolds; Rose Pipes (2006). The Biographical Dictionary of Scottish Women. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 216. ISBN 9780748626601.

- ^ a b Cumming, Elizabeth (November 2014). "The Arts and Crafts Movement in Scotland: A History Annette Carruthers". The Journal of Modern Craft. 7 (3): 335–339. doi:10.2752/174967714x14111311183126. ISSN 1749-6772. S2CID 191478727.

- ^ "Macbeth, Ann (1875–1948) GSA Archives". www.gsaarchives.net. Archived from the original on 13 August 2016. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- ^ Arthur, Liz (1992). Jessie Newbery (1864–1948), pp. 147–51, Glasgow Girls. Women in Art and Design, 1880-1920. (Ed. Jude Burkhauser). University of California Press. p. 151. ISBN 9780520083394.

- ^ Scottish National Exhibition: Catalogue of the Decorative and Ecclesiastical Arts Section. Glasgow: Dalross Limited. 1911. p. 1.

- ^ "Ann Macbeth: Book Designer". GSofA Library. 10 March 2015. Archived from the original on 19 December 2017. Retrieved 25 November 2017.

- ^ Walker, Lynne; Callen, Anthea (1980). "Women Artists of the Arts and Crafts Movement, 1870-1914". Woman's Art Journal. 1 (2): 69. doi:10.2307/1358090. ISSN 0270-7993. JSTOR 1358090.

- ^ a b c d Juliet Ash, Elizabeth Wilson (1990). Chic Thrills: A Fashion Reader. Edinburgh: Canongate. pp. 221–222. ISBN 1-84195-151-X.

- ^ Lynn Abrams (2006). Gender in Scottish History Since 1700. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 62. ISBN 9780748626397.

- ^ Elizabeth Crawford (2003). The Women's Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide 1866-1928. Routledge. p. 254. ISBN 9781135434021.

- ^ a b "Glasgow Girl Ann Macbeth and a Recent Acquisition". The Glasgow School of Art’s Archives and Collections. GSA Archives and Collections. 2015. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- ^ Elizabeth Wilson (1989). Through the Looking Glass: A History of Dress from 1860 to the Present Day. BBC Books. p. 62. ISBN 9780563214410.

- ^ "Hand, Heart & Soul – The Arts and Crafts Movement in Scotland". GSA Archives and Collections. 8 December 2014. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- ^ Garrett, Miranda; Thomas, Zoë, eds. (2019). Suffrage and the Arts. doi:10.5040/9781350011847. ISBN 9781350011847. S2CID 158163466.

- ^ Linda Cluckie (2008). The Rise and Fall of Art Needlework: Its Socio-economic and Cultural Aspects. Arena Books. p. 143. ISBN 9780955605574.

- ^ "Two Women of Distinction". The Glasgow Herald. 2 April 1948. Retrieved 9 February 2012.

- ^ "Macbeth, Ann (1875–1948)". TRC Needles. Textile Research Center. Retrieved 12 October 2017.

- ^ "Making the Glasgow Style". glasgowlife.org.uk. Archived from the original on 12 March 2020. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- ^ "The Studio Magazine (Ann Macbeth)". Heidelberg Historic Literature. Retrieved 12 December 2018.

- ^ "Educational Needlecraft by Margaret Swanson and Ann Macbeth". chestofbooks.com. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- ^ Macbeth, Ann (1930). "School and Fireside Crafts". Methuen & Co. Retrieved 6 August 2018.

- ^ Macbeth, Ann (1932). "The Country Woman's Rug Book". Dryad Press. Retrieved 6 August 2018.

- ^ Macbeth, Ann (1930). "Embroidered and Laced Leather Work". Methuen & Co. Retrieved 6 August 2018.

- ^ Davidson, Peter Wylie (1926). "Applied Design in the Precious Metals". farling.com/books - illustration on p64. Longmans. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- 1875 births

- 1948 deaths

- British embroiderers

- British modern artists

- Artists from Bolton

- Scottish artists

- Scottish non-fiction writers

- Alumni of the Glasgow School of Art

- Glasgow School

- British women writers

- Scottish women artists

- 20th-century British women artists

- Women's Social and Political Union

- 20th-century Scottish women writers

- People associated with Glasgow

- Scottish suffragettes

- Anglo-Scots

- Glasgow Society of Women Artists member

- 20th-century Scottish women artists

- 20th-century Scottish women educators

- 20th-century Scottish educators