Filippo Brunelleschi

Filippo di ser Brunellesco di Lippo Lapi | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Filippo di ser Brunellesco di Lippo Lapi[1] 1377 |

| Died | 15 April 1446 (aged 68–69) Florence |

| Known for | Architecture, sculpture, mechanical engineering |

| Notable work | Dome of Florence Cathedral |

| Movement | Early Renaissance |

Filippo di ser Brunellesco di Lippo Lapi (1377 – 15 April 1446), commonly known as Filippo Brunelleschi (/ˌbruːnəˈlɛski/ BROO-nə-LESK-ee; Italian: [fiˈlippo brunelˈleski]) and also nicknamed Pippo by Leon Battista Alberti,[4] was an Italian architect, designer, goldsmith and sculptor. He is considered to be a founding father of Renaissance architecture. He is recognized as the first modern engineer, planner, and sole construction supervisor.[5][6] In 1421, Brunelleschi became the first person to receive a patent in the Western world.[7][8] He is most famous for designing the dome of the Florence Cathedral, and for the mathematical technique of linear perspective in art which governed pictorial depictions of space until the late 19th century and influenced the rise of modern science.[9][10] His accomplishments also include other architectural works, sculpture, mathematics, engineering, and ship design.[6] Most surviving works can be found in Florence.

Biography

[edit]Early life

[edit]Brunelleschi was born in Florence, Italy, in 1377.[11] His father was Brunellesco di Lippo (born c. 1331),[1] a notary and civil servant. His mother was Giuliana Spini; he had two brothers.[12] The family was well-off; the palace of the Spini family still exists, across from the Church of Santa Trinità in Florence.[13] The young Filippo was given a literary and mathematical education to enable him to follow the father's career. Being artistically inclined, however, Filippo, at the age of fifteen, was apprenticed as a goldsmith and a sculptor working with cast bronze. In December 1398 he became a master and joined the Arte della Seta, the wool merchants' guild, the wealthiest and most prestigious guild in the city, which also included jewellers and metal craftsmen.[6][14]

Sculpture – Competition for the Florence Baptistry doors

[edit]Brunelleschi's earliest surviving sculptures are two (or three) small silver sculptures of saints (1399–1400) made for the altar of Saint James in the Crucifix Chapel of Pistoia Cathedral San Zeno.[15] He paused this work for four months in 1400, when he was chosen to simultaneously serve two representative councils of the Florentine government.[16]

Around the end of 1400, the city of Florence decided to create a second pair of new sculpted and gilded bronze doors for the Florence Baptistery.[17][a] A competition was held in 1401 for the design, which drew seven competitors, including Brunelleschi and another young sculptor, Lorenzo Ghiberti. Each sculptor had to produce a single bronze panel, depicting the Sacrifice of Isaac within a Gothic four-leaf frame. The panels each had to contain Abraham, Isaac, the angel, two other figures as well as a donkey and a sheep imagined by the artists, and had to harmonize in style with the existing doors, created in 1330 by Andrea Pisano. The head of the jury was Giovanni di Bicci de' Medici, the founder of the heavily influential Medici dynasty, who became an important patron of Brunelleschi. The jury initially praised Ghiberti's panel. When they saw Brunelleschi's work, they were unable to choose between the two and suggested that the two artists collaborate on the project.[18] Brunelleschi refused to forfeit total control of the project, preferring it to be awarded to Ghiberti. This divided public opinion.[18]

Brunelleschi would eventually abandon sculpture and devote his attention entirely to architecture and optics,[19] but continued to receive sculpture commissions until at least 1416.[20]

-

St. John the Evangelist, Silver Altar of Saint James, Pistoia Cathedral (1399–1400)

-

Jeremiah and Isaiah, altarpiece of St. James

-

The Sacrifice of Isaac, Brunelleschi's competition panel for the Baptistry door in Florence (1401), Bargello

Rediscovery of antiquity (1402–1404)

[edit]During the Early Renaissance, there was a growing interest in Ancient Greece and Rome as cultural roots that were to be revived to overcome medieval times, whose art was largely dominated by Byzantine models and foreign Gothic art from the North. Initially this cultural interest was borne by a few scholars, writers, and philosophers. It later became more influential across the visual arts.[21][citation needed] In this period (1402–1404),[22] Brunelleschi visited Rome, almost certainly accompanied by his younger friend, the sculptor Donatello, to study its ancient ruins.[23] Donatello may have been trained as a goldsmith, like Brunelleschi, and is later accounted for working in the studio of Ghiberti. Although the glories of Ancient Rome were a matter of popular discourse at the time, it was a foremost literary interest, and only few people had studied the physical conditions of its architectural ruins in any detail until Brunelleschi and Donatello did so. Brunelleschi's study of classical Roman architecture influenced his building designs including even lighting, the minimization of distinct architectural elements within a building, and the balancing of those elements to homogenize the space.[24]

It has been speculated that Brunelleschi developed his system of linear perspective after observing the Roman ruins.[20] However, some historians dispute that he visited Rome then, given the number of projects Brunelleschi had in Florence at the time, the poverty and lack of security in Rome during that period, and the missing evidence of the visit.[25][page needed] His first definitively documented stay in Rome was in 1432.

The Foundling Hospital (1419–1445)

[edit]

Brunelleschi's first architectural commission was the Ospedale degli Innocenti (1419–c. 1445), or Foundling Hospital, designed as a home for orphans. The Guild of the Silk Merchants owned, funded and managed the hospital.[27] As with many of Brunelleschi's architectural projects, the building was completed after a significant time lapse and with considerable modifications by other architects. He was the official architect until 1427, but he was rarely on site after 1423. The hospital was finished by the Florentine architect Francesco Della Luna in 1445.[28][29]

The major portion created by Brunelleschi was the exterior arcade or loggia some steps elevated above the pavement of the piazza. Nine semicircular arches on ten slender round columns with composite capitals are flanked by angular fluted pilasters on the facade. The vaults show no rips. On both ends feigned door frames with typanums decorate the walls. Three doors equally apart from one another open to the interior. This first arcade, with its clear reference to classical antiquity in its simple form and decoration, became an established model for numerous Renaissance buildings across Europe.[28] The building's style was dignified and sober, with no displays of fine marble or decorative inlays (The glazed terracotta reliefs in the tondos by Andrea della Robbia were put up not until 1490).[30]

-

Arcade of the Foundling Hospital (1419–1445) on the Piazza of Santissima Annunziata with its corresponding portico by Giovanni Battista Caccini (1601)

-

Cloister of Men of the Foundling Hospital (1419–1445)

-

Corinthian column in the cloister

Thereafter Brunelleschi was awarded additional commissions, like the Ridolfi Chapel in the church of San Jacopo sopr'Arno (not surviving), and the Barbadori Chapel in Santa Felicita (since modified). In both projects Brunelleschi devised elements already used in the Ospedale degli Innocenti, and which would also be used in the Pazzi Chapel and the Sagrestia Vecchia. In these first projects he piloted ideas which he would later employ in his most famous work, the dome of the Cathedral of Florence.

Basilica of San Lorenzo (1421–1442)

[edit]Brunelleschi undertook the major project of the Basilica of San Lorenzo soon after he had begun the Foundling Hospital. The former cathedral of Florence became again the largest church of the city, through the sponsorship of the Medici family, as their parish church and mausoleum. Numerous architects worked at the church, including Michelangelo. Brunelleschi designed the central nave, with the two collateral naves on either side (later lined by small chapels), and the Old Sacristy.[citation needed]

The first stage of the project was the Sagrestia Vecchia, the "Old Sacristy", built between 1419 and 1429 southwest of the existing church on the initial rebuildable ground. It houses the tomb of Giovanni di Bicci de' Medici and his wife, Piccarda Bueri. The chapel is a cube with a lateral length of about 11 metres (36 feet), covered with a hemispheric dome, that is without any decoration beside its twelve ribs that converge in an oculus, and the oculi of the arched tambour, which serve as light source. A level of ornamental entablatures divides the vertical space into two parts, and fluted pilasters at the edges structure the walls. By using classical elements in an innovative way, the interior established itself as a standard in Renaissance architecture.[31]

In the church itself, slender columns with Corinthian capitals along the nave replace the former massive pillars. Instead of traditional vaults a coffered ceiling of square compartments with delicately gilded trim covers the central nave. Its height is realized by a second story pierced by upright arched windows. Oculi above each chapel bridge the difference in height to the side aisles. The new interior projected an impression of harmony and balance.[32]

Brunelleschi used white walls in the Old Sacristy, which became a common element of Renaissance architecture. Leon Battista Alberti, who wrote the standard text on architecture of the time (1452), argued that, according to prominent classical authors like Cicero and Plato, white was the only color suitable for a temple or church and praised "the purity and simplicity of the color, like that of life."[33]

-

Nave of the Basilica of San Lorenzo (1425–1442)

-

View of the Old Sacristy (Sagrestia vecchia)

-

Vault of the Old Sacristy

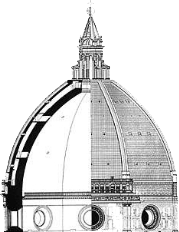

Florence Cathedral dome (1420–1461)

[edit]Santa Maria del Fiore was the cathedral and symbol of Florence, which had been begun in 1296. After the death of the first architect, Arnolfo di Cambio, work was interrupted for fifty years. The campanile, or bell tower, was begun by Giotto soon after 1330. Between 1334 and 1366 a committee of architects and painters made a plan of a proposed cupola, and the constructors were sworn to follow the plan. The proposed dome from the base to the lantern on top was more than 80 m (260 ft) high, and the octagonal base was almost 42 m (138 ft) in diameter. It was larger than the dome of the ancient Pantheon, or any other dome in Europe, and no dome of that size had been built since antiquity.[34]

A competition was held in 1418 to select the builder, and other competitors included his old rival Ghiberti. It was won by Brunelleschi, with the help of a brick scale model of the dome made for him by his friend the sculptor Donatello.[34] Since buttresses were forbidden by the city fathers, and because obtaining rafters for scaffolding long and strong enough (and in sufficient quantity) for the task was impossible, how a dome of that size could be constructed without its collapsing under its own weight was unclear. Furthermore, the stresses of compression were not clearly understood, and the mortars used in the period would set only after several days, keeping the strain on the scaffolding for a long time.[35]

The work on the dome (built 1420–1436), the lantern (built 1446–c. 1461) and the exedra (built 1439–1445) occupied most of the remainder of Brunelleschi's life.[36] Brunelleschi's success can be attributed to his technical and mathematical genius.[37] More than four million bricks were used in the construction of the octagonal dome. Notably, Brunelleschi left behind no building plans or diagrams detailing the dome's structure; scholars surmise that he constructed the dome as though it were hemispherical, which would have allowed the dome to support itself.[38]

Brunelleschi constructed two domes, one within the other, a practice that would later be followed by all the successive major domes, including those of Les Invalides in Paris and the United States Capitol in Washington. The outer dome protected the inner shell from the rain and allowed a higher and more majestic form. The frame of the dome is composed of twenty-eight horizontal and vertical marble ribs, or eperoni, eight of which are visible on the outside. The visible ones are largely decorative, since the outer dome is supported by the structure of the inner dome. A narrow stairway runs upward between the two shells to the lantern at the top.[34] Older examples of double-shelled domes include the 50 meter tall Dome of Soltaniyeh and the Mausoleum of Khoja Ahmed Yasawi.

Brunelleschi invented a new hoisting machine for raising the masonry needed for the dome, a task no doubt inspired by republication of Vitruvius' De architectura, which describes Roman machines used in the first century AD to build large structures such as the Pantheon and the Baths of Diocletian, structures still standing, which he could have seen for himself. This hoisting machine would be admired by Leonardo da Vinci years later.[39]

The strength of the dome was improved by the wooden and sandstone chains invented by Brunelleschi, which acted like tensioning rings around the base of the dome and reduced the need for flying buttresses, so popular in Gothic architecture.[40] The herringbone brick-laying pattern (Opus spicatum), which Brunelleschi may have seen in Rome, was also seemingly forgotten in Europe before the construction of the dome.[41]

Brunelleschi kept his workers up in the building during their breaks and brought food and diluted wine, similar to that given to pregnant women at the time, up to them. He felt the trip up and down the hundreds of stairs would exhaust them and reduce their productivity.[42]

Once the dome was completed, a new competition was held in 1436 for the decorative lantern on top of the dome, once again, among others, against his old rival Ghiberti. Brunelleschi won the competition and designed the structure and built the base for the lantern, but he did not live long enough to see its final installation atop the dome.[43]

In 1438 Brunelleschi designed his last contribution to the cathedral; four hemispherical exedra, or small half-domes, following a Roman model, set against the drum, the upright base of the main dome. The four small domes were altered and arranged to appear like a stairway of domes mounting upward. They were purely decorative and were enriched with horizontal entablatures and vertical arches, pilasters, and double columns. The technological advancements of gunpowder and portable cannons required a new system of fortification which led to further development of the double shelled dome.[44] Their architectural elements inspired later High Renaissance architecture, including the Tempietto of St. Peter built at Montorio by Bramante (1502). A similar structure appears in the painting of an ideal city attributed to Piero della Francesca at Urbino (about 1475).[45] The new designs fulfilled the need for the architectural expression for the status of ruling kings and princes while the strong dome structure symbolized the protection of their interests and bloodline.[46]

-

Dome of the Cathedral

-

Plan of the dome, showing the inner and outer shells

-

Interior structure of the dome

Pazzi Chapel (1430–1444)

[edit]The Pazzi Chapel in Florence was commissioned in about 1429 by Andrea Pazzi to serve as the chapter house, or meeting place of the monks of the Monastery of Santa Croce. Like nearly all of his works, the actual construction was delayed, beginning only in 1442, and the interior was not finished until 1444. The building was completed twenty years after his death, in about 1469, including some of the details, such as the lantern on top of the dome.[47]

The portico of the chapel is especially notable for its fine proportions, simplicity, and harmony. Its centerpiece is a sort of arch of triumph. Its six columns support an entablature with sculpted tondos, an upper level divided by pilasters and a central arch, and another band of sculpted entablature at the top, below a terrace and the simple cupola. The interior space is framed by arches, entablatures, and pilasters, all in local pietra serena. The floor is also divided into geometric sections. Light comes downward from the circular windows of the dome, and changes throughout the day. The interior is given touches of color by circular blue and white glazed terracotta reliefs by Luca Della Robbia. The architecture of the chapel is based on an arrangement of rectangles, rather than squares, which makes it appear slightly less balanced than the Old Sacristy of San Lorenzo.[47]

-

Facade of the Pazzi Chapel

-

Plan of the Pazzi Chapel

Santa Maria degli Angeli (1434–1437)

[edit]Santa Maria degli Angeli was an unfinished project by Brunelleschi which introduced a revolutionary concept in Renaissance architecture. Churches since the Romanesque and Gothic periods were traditionally in the form of a cross, with the altar in the crossing, a central chapel or an apse. Santa Maria deli Angeli was designed as a rotunda in an octagonal shape, with each side containing a chapel, and the altar in the center.

The financing of the church came from the legacy of two Florentine merchants, Matteo and Andrea Scolari, and construction commenced in 1434. However, in 1437, the money for the church was seized by the Florentine government to help finance a war against the neighboring city of Lucca. The structure, which had reached a height of 7 m (23 ft), was never completed as Brunelleschi designed it. The completed part was later integrated into a later church of a different design.[48]

The plans and model of Brunelleschi's church are lost, and it is known only from an illustration in the Codex Rustici from 1450, and from drawings of other architects. Leon Battista Alberti, in his De re aedificatoria, the first major treatise on Renaissance architecture, written around 1450 and printed in 1485, hailed the design as the "first complete plan of a Renaissance church." Leonardo da Vinci visited Florence in about 1490, studied Brunelleschi's churches and plans, and sketched a plan for a similar octagonal church with radiating chapels in his notebooks. It reached its fruition on an even larger scale in the 16th century. Donato Bramante proposed a similar central plan with radiating chapels for his Tempieto, and later, on an even larger scale, in his plan for Saint Peter's Basilica (1485–1514).[49] The central plan was finally realized, with some modifications, beginning in 1547, in Saint Peter's by Michelangelo and its deviating completion by Carlo Maderna.[50]

-

1450 Codex Rustici drawing showing Brunelleschi's proposed octagonal church (lower right)

-

Brunelleschi's rotunda from Santa Maria degli Angeli. Only the lower wall remains of his original design.

-

Plan of the rotunda of Santa Maria degli Angeli

-

Michelangelo's plan for Saint Peter's Basilica, Rome (1546), superimposed on the earlier plan by Bramante

Basilica of Santo Spirito (1434–1466)

[edit]The Basilica of Santo Spirito in Florence was his last major commission, which, characteristically, he carried out in parallel with his other works. Though he began designing in 1434, construction did not begin until 1436, and continued beyond his lifetime. The columns for the facade were delivered in 1446, ten days before his death. The facade was finally completed in 1482, and then was modified in the 18th century. The bell tower is also a later addition.[51]

Santo Spirito is an example of the mathematical proportion and harmony of Brunelleschi's work. The church is in the form of a cross. The choir, the two arms of the transept, and the space in the center of the transept are composed of squares exactly the same size. The continuation of the nave contains four more identical squares (The half-square at the end is a later addition). The length of the transept is exactly half of the total length of the nave. Each square of the lower collateral naves is one-quarter the size of the squares in the principal nave. The side aisles are lined with thirty-eight small chapels, which were later fitted with altars decorated with devotional art works.[51]

The vertical plan is also perfectly in proportion; the height of the central nave is exactly twice its width, and the height of the collateral naves on either side are exactly twice their width. Other aspects of his original plan, however, were modified after his death. The main aisle of the nave, lined by columns with Corinthian capitals, is topped by a row of semicircular moulded arches. His original plan called the ceiling of the nave to be composed of a barrel vault, which would have echoed the collateral naves, but this was also changed after his death to the flat coffered ceiling. Little remains of the exterior walls that he had planned. They were unfinished at his death and were covered with a facade in Baroque style.[51]

-

Central nave of Santo Spirito

-

Brunelleschi's plan of Santo Spirito

-

Detail of the classical pilasters of the sacristy

Accomplishments

[edit]Linear perspective

[edit]Besides his accomplishments in architecture, Brunelleschi is also credited as the first person to describe a precise system of linear perspective. This revolutionized painting opening the way for the naturalistic styles from Renaissance art until the 19th century.[52] He systematically studied why and how objects, buildings, and landscapes changed their shape and lines appeared to converged when seen from a distance or from different angles.[53]

According to his early biographers Antonio Manetti (and Giorgio Vasari took it from him), Brunelleschi conducted experiments between 1415 and 1420, including making paintings with perspectives of the Florence Baptistery viewed from the entrance of the Cathedral, and the Palazzo Vecchio, seen obliquely from its northwest corner on Piazza della Signoria. According to Manetti, he used a grid to guide the drawing of the scene square by square and produced a reverse image. He geometrically calculated a scale for the objects in the drawing to make them appear accurately, thus discovering a system to represent three dimensional objects on a two-dimensional surface.[54] The results were compositions with accurate perspective, as seen through a mirror. To compare the truthfullness of his image with the real object, he made a small hole in his painting, and had an observer look through the back of the painting to observe the scene. A mirror was then raised, reflecting Brunelleschi's composition, and the observer saw the striking similarity between the reality and painting. Both panels have since been lost.[55][56]

Brunelleschi's studies on perspective were extended by Leon Battista Alberti, Piero della Francesca and Leonardo da Vinci. Following the rules of perspective studied by Brunelleschi and the others, artists could paint imaginary landscapes and scenes with accurate three-dimensional perspective and realism. The most important treatise on painting of the Renaissance, Della pittura by Alberti, was published in 1436 and dedicated to "Pippo" Brunelleschi, whose experiment Alberti described in its third book. The painting of The Holy Trinity by Masaccio (1425–1427) in the church of Santa Maria Novella, Florence, is a renowned early example of the new technique, which accurately created the illusion of a three-dimensional space and also adopted, in painting, Brunelleschi's architectural style. This established the standard method for artists (working on two-dimensional surfaces like paper or canvas) until the 19th century.[57]

-

The Holy Trinity (upper part) by Masaccio (1425–1427) used Brunelleschi's system of perspective

-

Diagram of Brunelleschi's experiment in perspective

-

The Delivery of the Keys, fresco by Perugino in the Sistine Chapel (1481–1482), features both linear perspective and Brunelleschi's architectural style

An innovative boat

[edit]

In 1421, Brunelleschi was granted what is thought to be one of the first modern patents for his invention of a river transport vessel that was said to "bring in any merchandise and load on the river Arno etc for less money than usual, and with several other benefits."[58][59] It was intended to be used to transport marble. In the history of patent law, Brunelleschi is, therefore, accorded a special place.[59] In cultural and political terms, the granting of the patent was part of Brunelleschi's attempt to operate as a creative and commercial individual outside the constraints of the guilds and their monopolies.[58]

He was also active in shipbuilding. In 1427 he built a large boat named Il Badalone to transport marble to Florence from Pisa up the River Arno. The ship sank on its maiden voyage, along with a sizable portion of Brunelleschi's personal fortune.[60]

Other activities

[edit]Brunelleschi's interests extended to mathematics and engineering and the study of ancient monuments. He designed hydraulic machinery and elaborate clockworks, none of which survive.

Brunelleschi designed machinery for use in churches during theatrical religious performances that re-enacted Biblical miracle stories. Contrivances were created by which characters and angels were made to fly through the air in the midst of spectacular explosions of light and fireworks. These events took place during state and ecclesiastical visits. It is not known for certain how many of these projects Brunelleschi designed, but at least one, for the church of San Felice, is confirmed in the records.[27]

Brunelleschi also designed fortifications used by Florence in its military confrontations with Pisa and Siena. In 1424, he worked in Lastra a Signa, a village protecting the route to Pisa, and in 1431, in the south of Italy at the walls of the village of Staggia. These walls are still preserved, but their attribution to Brunelleschi is uncertain.

His works involved sometimes urban planning; he strategically positioned several of his buildings in relation to the nearby squares and streets to increase their visibility. For example, demolitions in front of San Lorenzo were approved in 1433 to create a piazza facing the church. At Santo Spirito, he suggested that the façade be turned either towards the Arno so travellers would see it, or to the north, to face a large piazza.

Personal life

[edit]Brunelleschi did not have children of his own, but in 1415, he adopted Andrea di Lazzaro Cavalcanti, who took the name Il Buggiano, after his birthplace. He was Brunelleschi's sole heir.[61]

Brunelleschi was a member of the guild of silk merchants, which included jewelers and goldsmiths, but not of the guild of stone and wood masters, which included architects. In 1434, he was arrested at the request of the guild of masters of stone and wood for practicing his trade illegally. He was quickly released, and the stone and wood masters were charged with false imprisonment.[62]

Location of remains

[edit]Brunelleschi's body lies in the crypt of the Cathedral of Florence. Antonio Manetti, who knew Brunelleschi and wrote his biography that Brunelleschi "was granted such honours as to be buried in the Basilica di Santa Maria del Fiore, and with a marble bust, which was said to be carved from life, and placed there in perpetual memory with such a splendid epitaph."[63] Inside the cathedral entrance is this epitaph: "Both the magnificent dome of this famous church and many other devices invented by Filippo the architect, bear witness to his superb skills. Therefore, in tribute to his exceptional talents, a grateful country that will always remember him buries him here in the soil below." A statue of Brunelleschi, looking up at his dome, was later placed in the square in front of the cathedral.

Fictional depictions

[edit]In 2016, Brunelleschi was played by Alessandro Preziosi in the 2016 television series Medici: Masters of Florence.

Brunelleschi was portrayed by John Rowe in a 1995 audio drama by Jean Binnie titled Battle for the Dome, which was produced by BBC Radio 4 in 2025.[64]

Principal works

[edit]The principal buildings and works designed by Brunelleschi or which included his involvement, all situated in Florence:[65]

- Dome of the Florence Cathedral (1419–1436)

- Ospedale degli Innocenti (1419–ca.1445)

- The Basilica of San Lorenzo (1419–1480s)

- Meeting Hall of the Palazzo di Parte Guelfa (1420s–1445)

- Sagrestia Vecchia, or Old Sacristy of S. Lorenzo (1421–1440)

- Santa Maria degli Angeli: unfinished, (begun 1434)

- The lantern of Florence Cathedral (1436–ca.1450)

- The exedrae of Florence Cathedral (1439–1445)

- The church of Santo Spirito (1441–1481)

- Pazzi Chapel (1441–1460s)

-

Brunelleschi designed the Rocca di Vicopisano

-

Palazzo Lenzi, Piazza Ognissanti, Florence, 1470, attributed to Brunelleschi, sgrafitti by Andrea Feltrini

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Footnotes

- ^ These may have been meant to celebrate the signing of a treaty between Milan and Venice or the end of a deadly epidemic of the Black Death.[17]

Citations

- ^ a b Walker 2003, p. 5.

- ^ "The Duomo of Florence | Tripleman". tripleman.com. Retrieved March 25, 2010.

- ^ "brunelleschi's dome – Brunelleschi's Dome". Brunelleschisdome.com. Archived from the original on April 16, 2010. Retrieved March 25, 2010.

- ^ "Il miracolo della cupola di "Pippo" Brunelleschi" (in Italian). corriere.it. June 11, 2020. Retrieved November 26, 2020.

- ^ Bodart, Diane (2008). Renaissance & Mannerism. New York: Sterling. ISBN 978-1402759222.

- ^ a b c Fanelli, Giovanni (1980). Brunelleschi. Harper & Row. p. 3.

- ^ Kwong, Matt (November 4, 2014). "Six significant moments in patent history". Reuters. Retrieved May 19, 2021.

- ^ "150 years – patents". Wilsongunn.com. Retrieved May 19, 2021.

- ^ Campbell, Stephen J; Cole, Michael Wayne (2012). Italian Renaissance Art. London/New York: Thames & Hudson. pp. 95–97.

- ^ Edgerton, Samuel Y (2009). The Mirror, the Window, and the Telescope: How Renaissance Linear Perspective Changed Our Vision of the Universe. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- ^ Bruschi, Arnaldo (2006). Filippo Brunelleschi. Milano: Electa. p. 9.

- ^ Manetti, Antonio (1970). The Life of Brunelleschi. Translated by Enggass, Catherine. Pennsylvania State University Press. pp. 36–38.

- ^ Gärtner 1998, p. 11.

- ^ Walker 2003, p. 4.

- ^ Gärtner 1998, p. 20.

- ^ Walker 2003, p. 9.

- ^ a b Walker 2003, p. 15.

- ^ a b Walker 2003, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Paoletti, John T; Radke, Gray M (2012). Art in Renaissance Italy. Upper Saddle River, N.J: Pearson Prentice Hall. pp. 203–205.

- ^ a b De la Croix, Horst; Tansey, Richard G.; Kirkpatrick, Diane (1991). Gardner's Art Through the Ages (9th ed.). Thomson/Wadsworth. p. 592. ISBN 0-15-503769-2.

- ^ Ulrich Pfisterer. Donatello und die Entdeckung der Stile (Römische Studien der Bibliotheca Hertziana, 17). Hirmer, München 2002, full text online (German).

- ^ Manetti and Vasari ? proper [citation needed]

- ^ Coonin, 24–25.

- ^ Meek, Harold (2010). "Filippo Brunelleschi". Grove Art Online. doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T011773. ISBN 978-1-884446-05-4.

- ^ Gärtner 1998.

- ^ Marinazzo, Adriano (2010). "La restituzione digitale della fronte porticata dell'Ospedale degli Innocenti da Brunelleschi a Della Luna (1420-1440)". Il Mercante l'Ospedale I Fanciulli (in Italian): 86–87. See also Adriano Marinazzo at Academia.edu.

- ^ a b Battisti, Eugenio (1981). Filippo Brunelleschi. New York: Rizzoli. ISBN 0-8478-5015-3.

- ^ a b Gärtner 1998, p. 28.

- ^ Fanelli, Giovanni (1980). Brunelleschi. Firenze: Harper & Row. p. 41.

- ^ Klotz, Heinrich (1990). Filippo Brunelleschi: the Early Works and the Medieval Tradition. Translated by Hugh Keith. London: Academy Editions. ISBN 0-85670-986-7.

- ^ Gärtner 1998, pp. 56–58.

- ^ Gärtner 1998, pp. 36–40.

- ^ Gärtner 1998, p. 63.

- ^ a b c Gärtner 1998, p. 86.

- ^ King, Ross (2001). Brunelleschi's Dome: The Story of the Great Cathedral of Florence. New York: Penguin. ISBN 0-8027-1366-1.

- ^ Saalman, Howard (1980). Filippo Brunelleschi: The Cupola of Santa Maria del Fiore. London: A. Zwemmer. ISBN 0-302-02784-X.

- ^ Prager, Frank (1970). Brunelleschi: Studies of his Technology and Inventions. Cambridge: The MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-16031-5.

- ^ Jones, Barry; Sereni, Andrea; Ricci, Massimo (January 1, 2008). "Building Brunelleschi's Dome: A practical methodology verified by experiment". Construction History. 23: 3–31. JSTOR 41613926.

- ^ "Leonardo da Vinci - Sketch of Brunelleschi's light hoist". brunelleschi.imss.fi.it. Museo Gallileo.

- ^ Prager, Frank D. (1950). "Brunelleschi's Inventions and the "Renewal of Roman Masonry Work"". Osiris. 9: 457–554. doi:10.1086/368537. ISSN 0369-7827. JSTOR 301857. S2CID 143092927.

- ^ James-Chakraborty, Kathleen (2014). Architecture since 1400. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. pp. 30–43. ISBN 9781452941714.

- ^ "The Medici Popes". Medici: Godfathers of the Renaissance. February 18, 2004. PBS. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- ^ Gärtner 1998, pp. 95–96.

- ^ Principe, Lawrence (2011). The Scientific Revolution: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford. pp. 198–199. ISBN 9780191620164.

- ^ Gärtner 1998, pp. 102–109.

- ^ Principe, Lawrence (2011). The Scientific Revolution: A Very Short Introduction. OUP Oxford. p. 199. ISBN 9780191620164.

- ^ a b Gärtner 1998, pp. 68–77.

- ^ Gärtner 1998, p. 78.

- ^ Gärtner 1998, p. 82.

- ^ Gärtner 1998, pp. 82–84.

- ^ a b c Gärtner 1998, pp. 44–55.

- ^ "...and these works [of perspective by Brunelleschi] were the means of arousing the minds of the other craftsmen, who afterwards devoted themselves to this with great zeal."

Vasari. "The Life of Brunelleschi." In: Lives of the Artists - ^ Gärtner 1998, pp. 22–25.

- ^ "Gaining Perspective". Nelson-Atkins. Retrieved March 18, 2025.

- ^ Edgerton, Samuel Y. (2009). The Mirror, the Window & the Telescope: How Renaissance Linear Perspective Changed Our Vision of the Universe. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. pp. 44–46. ISBN 978-0-8014-4758-7.

- ^ Gärtner 1998, p. 23.

- ^ Gärtner 1998, p. 25.

- ^ a b Prager, Frank D (1946). "Brunelleschi's Patent". Journal of the Patent Office Society. 28: 120.

- ^ a b Griset, Pascal (2013) The European Patent http://documents.epo.org/projects/babylon/eponet.nsf/0/8DA7803E961C87BBC1257F480049A68B/$File/european_patent_book_en.pdf

- ^ "Brunelleschi's Monster Patent: Il Badalone". www.cpaglobal.com. Archived from the original on July 29, 2012.

- ^ "Andrea di Lazzaro Cavalcanti, called Il Buggiano, died on 21 February 1462 in Florence. – Italian Art Society".

- ^ Gärtner 1998, p. 115.

- ^ Manetti, Antonio (1970). The Life of Brunelleschi. English translation of the Italian text by Catherine Enggass. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 0-271-00075-9.

- ^ "BBC Radio 4 Extra - Battle for the Dome by Jean Binnie". BBC. Retrieved May 24, 2025.

- ^ "Filippo Brunelleschi | Biography, Artwork, Accomplishments, Dome, Linear Perspective, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. February 14, 2025. Retrieved February 15, 2025.

Bibliography

[edit]- Goonin, A. Victor, Donatello and the Dawn of Renaissance Art, 2019, Reaktion Books, ISBN 9781789141306

- Gärtner, Peter (1998). Brunelleschi (in French). Cologne: Konemann. ISBN 3-8290-0701-9.

- Oudin, Bernard (1992), Dictionnaire des Architects (in French), Paris: Seghers, ISBN 2-232-10398-6

- Walker, Paul Robert (2003). The Feud That Sparked the Renaissance: How Brunelleschi and Ghiberti Changed the Art World. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-380-97787-7.

Further reading

[edit]- Argan, Giulio Carlo; Robb, Nesca A (1946). "The Architecture of Brunelleschi and the Origins of Perspective Theory in the Fifteenth Century". Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes. 9: 96–121. doi:10.2307/750311. JSTOR 750311. S2CID 190022297.

- Fanelli, Giovanni (2004). Brunelleschi's Cupola: Past and Present of an Architectural Masterpiece. Florence: Mandragora.

- Heydenreich, Ludwig H. (1996). Architecture in Italy, 1400–1500. New Haven/London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-06467-4.

- Hyman, Isabelle (1974). Brunelleschi in perspective. Prentice-Hall.

- Kemp, Martin (1978). "Science, Non-science and Nonsense: The Interpretation of Brunelleschi's Perspective". Art History. 1 (2): 134–161. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8365.1978.tb00010.x.

- Prager, F. D. (1950). "Brunelleschi's Inventions and the 'Renewal of Roman Masonry Work'". Osiris. 9: 457–554. doi:10.1086/368537. S2CID 143092927.

- Millon, Henry A.; Lampugnani, Vittorio Magnago, eds. (1994). The Renaissance from Brunelleschi to Michelangelo: the Representation of Architecture. London: Thames and Hudson.

- Trachtenberg, Marvin (1988). What Brunelleschi Saw: Monument and Site at the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence. New York.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - King, Ross (2000). Brunelleschi's Dome: How a Renaissance Genius Reinvented Architecture. New York: Walker. ISBN 0-8027-1366-1.

- Devémy, Jean-François (2013). Sur les traces de Filippo Brunelleschi, l'invention de la coupole de Santa Maria del Fiore à Florence. Suresnes: Les Editions du Net. ISBN 978-2-312-01329-9. (in line presentation Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine)

- Saalman, Howard (1993). Filippo Brunelleschi: The Buildings. Penn State Press. ISBN 0271010673.

- Vereycken, Karel, "The Secrets of the Florentine Dome", Schiller Institute, 2013. (Translation from the French, "Les secrets du dôme de Florence", la revue Fusion, n° 96, Mai, Juin 2003)

- "The Great Cathedral Mystery", PBS Nova TV documentary, February 12, 2014

External links

[edit]- Filippo Brunelleschi

- Italian Renaissance architects

- Italian civil engineers

- 1377 births

- 1446 deaths

- Architects of cathedrals

- Architects from Florence

- 14th-century people from the Republic of Florence

- 15th-century people from the Republic of Florence

- Italian Roman Catholics

- History of patent law

- 15th-century Italian engineers

- 15th-century Italian architects

- 15th-century Italian sculptors

- Architects of Roman Catholic churches

- Catholic sculptors