Enki

| Enki 𒀭𒂗𒆠 | |

|---|---|

God of subterranean fresh waters, wisdom, crafts, creation, magic and incantations [1] | |

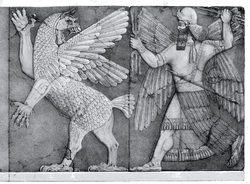

Detail of Enki from the Adda Seal, an ancient Akkadian cylinder seal dating to circa 2,300 BCE[2] | |

| Other names | Ea, Nudimmud, Nagbu, Niššīku |

| Major cult center | Eridu, Malgium |

| Abode | Abzû |

| Symbol | ram-headed staff, goat-fish, turtle, ibex[3], vase with flowing waters[4] |

| Number | 40 |

| Genealogy | |

| Parents | |

| Siblings | |

| Consort | |

| Children | several, including Nanshe, Asalluhi, Marduk and Enbilulu[5] |

| Equivalents | |

| Ugaritic | Kothar-wa-Khasis[13] |

| Egyptian | Ptah |

| Hurrian | Eyan[13] |

| Elamite | Napirisha[14] |

| Greek | possibly Prometheus[15][16] possibly Poseidon[17] |

| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Mesopotamian religion |

|---|

|

Enki (Sumerian: 𒀭𒂗𒆠 DEN-KI) is the Sumerian god of water, knowledge (gestú), crafts (gašam), and creation (nudimmud), and one of the Anunnaki. He was later known as Ea (Akkadian: 𒀭𒂍𒀀) or Ae[18] in Akkadian (Assyrian-Babylonian) religion, and is identified by some scholars with Ia in Canaanite religion. The name was rendered Aos within Greek sources (e.g. Damascius).[19]

He was originally the patron god of the city of Eridu, but later the influence of his cult spread throughout Mesopotamia and to the Canaanites, Hittites and Hurrians. He was associated with the southern band of constellations called stars of Ea, but also with the constellation AŠ-IKU, the Field (Square of Pegasus).[20] Beginning around the second millennium BCE, he was sometimes referred to in writing by the numeric ideogram for "40", occasionally referred to as his "sacred number".[21][22] The planet Mercury, associated with Babylonian Nabu (the son of Marduk) was, in Sumerian times, identified with Enki,[23] as was the star Canopus.[24]

Many myths about Enki have been collected from various sites, stretching from Southern Iraq to the Levantine coast. He is mentioned in the earliest extant cuneiform inscriptions throughout the region and was prominent from the third millennium down to the Hellenistic period.

The names Enki and Ea

[edit]The meaning of the names Enki and Ea is uncertain. It is presumed that they were originally separate deities, though it is unclear when they were fully equated with each other.[25] Alfonso Archi argues that syncretism between them likely already existed at least from the mid third millenium BCE in parts of Babylonia.[26]

Enki

[edit]The name Enki is usually translated as “Lord of the Earth” in sumerian.[27] This explanation is not universally accepted.[28] Several scholars argue that it does not seemingly fit the functions of the god.[27][29] It has been proposed that Enki could have been an epithet of the deity that eventually replaced his original name.[30] Samuel Noah Kramer argued that the epithet ''Lord of the Earth'' was given to the god by the theologians of Eridu in order to elevate his position in the pantheon and make him a rival of Enlil.[29]However, Thorkild Jacobsen points out that there is no conclusive evidence of a rivalry between Enki and Enlil in Sumerian texts.[31] Jacobsen interpreted Enki as a personification of the power of sweet waters. He explained his name ‘’Lord (productive manager) of the Earth’’ as a reflection of the role of water in the fertilizing of the earth.[32] He proposed that Enki’s original name was Abzû, later regarded as his under-earth sweet water domain and living place.[33] However according to Peeter Espak there is no conclusive proof that Enki was regarded as an ancient personification of water in the available sources of the old sumerian period.[34] Despite the similarity between their names, Enki of Eridu and the primordial god Enki were separate figures.[35] Jacobsen proposed that their names had slightly different meanings and he translated the name of the primordial god as “Lord Earth”.[35]The forms of their names in the Emesal dialect are different; the name of Enki of Eridu is written Amanki, while the name of the primordial god is written Umunki.[36]

Edmond Sollberger and Wilfred G. Lambert have proposed a different translation for the name of Enki of Eridu. It has been remarked that an omissible g appears at the end of the second element of his name, which does not appear in the name of the primordial god.[37]For this reason they interpret this second element not as ki, ‘’earth’’, but as ki(g) of unknown meaning.[38] Sollberger understood an element ki(g) meaning ‘’favour, benevolence, love’’ in Sumerian. Therefore he translated Enki(g) as ‘’Lord Love’’,[39]or ‘’Lord Benevolence’’.[40] He argues that this translation reflects Enki’s well attested role in myths as a friend of mankind.[39] However, this explanation is not generally accepted. It has been remarked that it is possible that the omissible g developed via dissimilation,[41] though similar examples of dissimilation are so far not attested in Sumerian.[42]

Ea

[edit]The name Ea first occurs in personal names from the Old Akkadian period. Earlier translations interpreting Ea as a sumerian name meaning ‘’House of Water’’ or ‘’House of the Moon, Moon station’’ are regarded as implausible by modern scholarship.[43] In a few modern publications, the interpretation ‘’House of Water’’ is sometimes presented as a scribal popular etymology. However, according to Lambert, there is no evidence for such a reinterpretation.[28]

Due to the fact that the name appears associated with semitic elements in the sources of the Old Akkadian Period, it has been suggested that Ea is most likely a semitic name.[44]It has been proposed that the etymology of the name is connected to the semitic root ḥyy, ‘’to live’’.[45] This explanation has not been proved with certainty, though it is considered plausible.[46] Miguel Civil proposed that the name of the god Haya was originally an alternative spelling of Ea.[47] Margaret W. Green proposed that the names Ea and Haya were both derived from the name of a pre Sumerian deity that was integrated into the pantheons of the sumerians and of the semitic peoples, and that Haya persisted as a separate deity after Ea was syncretized with Enki.[48]The hypothesis of a connection between the names Ea and Haya is considered to be credible, but it is not proved, and it is not accepted by all scholars.[49]

Alternative names and epithets

[edit]Nudimmud

[edit]Nudimmud, one of the most frequently attested alternative names and epithets of Enki/Ea, was almost exclusively used in literary texts. In akkadian sources, it could also appear in royal inscriptions, prayers, and incantations.[50]It already appears in the Zame Hymns under the form den-nu-te-mud.[51] The standard writing was dnu-dím-mud. Alternative forms include, for example, nu-te-me-nud from the Fāra period or nu-da-mud from the Ur III period. The verbal elements dím and mud in the standard orthography respectively mean ‘’to build, create’’, and ‘’to bring forth’’.[52] The god list An=Anum ša ameli explains Nudimmud as Ea in his aspect as the god of creation.[51] Thorkild Jacobsen interpreted the name as ‘’Image fashioner’’, ‘’God of shaping’’, reflecting Ea’s role as the god of crafts and as the god who creates figures from clay.[32] It has been remarked that older spellings of Nudimmud do not feature the element dím.[53] Antoine Cavigneaux and Manfred Krebernik conclude that the orthography with dím is likely due to a later etymological reinterpretation of the name.[52]The meaning of Nudimmud in the older periods is unclear.[51]

Nagbu

[edit]Nagbu, ‘’Source, spring’’,[54] was an alternative name of Enki/Ea which reflected his role as the lord of the springs and subterranean waters. In this aspect he was not only connected to irrigation and fertility,[55] but he was also associated with the art of incantation, as subterranean water played an important role in Mesopotamian magic and incantation rituals.[56] Nagbu is attested chiefly in sources from Babylonia, and in the Neo Babylonian period, the name often appears in incantation texts.[57] It was written with the logogram dIDIM. This logogram already appears as a theophoric element in Akkadian and Neo Sumerian names.[55]Starting from the second millennium BC it often appears in Babylonian personal names.[57] In the god list An=Anum, Nagbu is equated with Ea. It is unclear whether Nagbu was originally an independent deity or an aspect of Ea.[56]

Niššīku

[edit]Niššīku was an alternative name and epithet of Enki/Ea of uncertain meaning. It is first attested in literary texts of the Old Babylonian period.[58] Wilfred G. Lambert and Alan R. Millard propose that the name was derived from the Semitic element nasīku ,’’chieftain’’, which reflects Enki’s sumerian epithet nun.[59] Hannes D. Galter considers that a connection between an Old Babylonian expression and a loanword from Aramaic is implausible.[58]Alternative spellings of the name include Naššīku and Ninšīku.[60] Ninšīku is likely a later folk etymology from Sumerian. It is attested from the Middle Babylonian period onwards.[58] One god list explains Ninšīku as Ea in his aspect as god of wisdom. In this interpretation, -šiku was likely equated with Sumerian kù-zu, ‘’wise’’.[60]

DIŠ

[edit]The logogram DIŠ often designates Enki/Ea in Assyrian texts. In Neo Assyrian sources, it chiefly appears in royal inscriptions and incantation literature.[61] It is sometimes attested as a theophoric element in personal names of the first millenium. In Neo Babylonian Uruk it designates Anu instead. The reading of DIŠ in akkadian is unknown. Galter suggests that DIŠ was possibly a numeral symbolizing the number 60, a number associated with Anu, and that its use for Ea could have been a way to equate him with the supreme god of the pantheon.[61]

Other names and epithets

[edit]Enki/Ea had a variety of other names and epithets reflecting his different functions and his association with his abode, Abzû, and his cult center, Eridu.[62] Galter remarks that the majority of other names of Ea are only documented from sources from the late second millennium, and therefore he presumes that they represent an effort to fully encompass and describe all of the aspects of the god.[63] Craftsmanship deities such as Uttu and Ninagal could be regarded as alternative names of Ea in late sources.[64]

The majority of akkadian epithets of Ea reflect his role as the god of wisdom.[65] Such epithets include for example, bēl nēmeqi (‘’Lord of wisdom’’),bēl tašīmti (‘’Lord of understanding’’),[66] and apkal ilī.(‘’Sage of the gods’’).[67] Bēl nagbi, (‘’Lord of the subterranean waters’’)[68] was a frequently attested epithet of Ea in his aspect as a water god.[57] He could be referred to as bēl tenēšēti, ‘’Lord of mankind’’.[69] His association to the arts of incantation was reflected in his epithets mašmaš ilī, ‘’Exorcist of the gods’’,[70] and bēl išīputti (‘’Lord of the purification rites’’).[68]

Ea could be referred to as Ea-šarru in some akkadian texts.[71] According to Galter, it is unclear whether Ea-šarru was simply an epithet of Ea or if a foreign deity was identified with Ea and -šarru,‘’king’’, was added to distinguish them. He remarks that the earliest attestations of this name occur outside of Mesopotamia, which could indicate that the name did not originate in the region.[72]

A common epithet of Enki/Ea in literary texts was Enlil-banda, ‘’the junior Enlil’’. An early attestation of this epithet dates to the Old Babylonian Period.[73] Several possible interpretations of this name have been suggested by scholars. It could indicate that Ea was regarded as a younger brother of Enlil, it could have been a way to equate Ea with Enlil, it could have been a way to assert that he is ‘’like Enlil’' in his domain,[74] or it could mean that he received his functions and abode from Enlil.[75]

Enki’s epithets king of the Abzû and king of Eridu are already attested in sumerian sources from the Early Dynastic Period.[76] Another of his epithets was (ddàra-abzu), translated as Ibex[77][3] or Stag[5] of the Abzû. The ibex was associated with Enki in historical times.[78] An early attestation of this byname is found in an Old Babylonian hymn. Several compound bynames of Enki/Ea formed with the element dàra appear in a later god list.[79][63]

Symbols and iconography

[edit]

Enki/Ea is considered one of the few Mesopotamian deities with a recognizable iconography.[80] His most distinguishing features are water streams flowing from his body, often accompanied by fish swimming in the water. These features are first attested in the Old Akkadian Period.[81] Enki’s iconography in the older periods is uncertain. It has been proposed that he is depicted on an Early Dynastic seal representing a sitting god with two fish beneath his feet,[82] though this identification is not universally accepted.[83] Enki/Ea’s water streams could be depicted as coming from his shoulders or his hips, or he could be depicted sitting within his shrine or abode, with the streams surrounding it in the shape of a rectangle.[84][5] Additionally, he could often be depicted with water sprouting vessels[4], carrying them either on his shoulders, in his hand or above his hand.[85]

His emblems include the goat-fish and the ram-headed staff.[86] They were often depicted together, for example on kudurrus.[87][88] The kudurru of Nazi-Maruttash refers to them as ‘’the great emblems of Ea’’.[88] The ram-headed staff is attested in art from the Old Babylonian period until the Achaemenid period. In Neo Assyrian seals, Ea is sometimes represented carrying a crook, which Jeremy Black and Anthony Green suggest may be a symbolic representation of the staff.[89] The goat-fish is attested in mesopotamian art from the Neo Sumerian period until Hellenistic times, and it was later adopted into roman art.[90] It is at the origin of the zodiacal constellation Capricorn.[91] Ea could often be represented sitting or standing on it.[88] While the goat-fish’s connection to Ea is well attested, it could also be depicted as a general apotropaic figure, not attached to any god.[92] Clay figurines of goat-fishes could be used in apotropaic magic.[88]

Another symbol of Ea was the turtle. It was associated with him since the Old Akkadian period.[93][94] On kudurrus it could be used as his symbol instead of the goat-fish with the ram-headed staff, or it could be represented on the back of the goat-fish.[95]

Ea was often depicted alongside his two faced vizier Isimud. Since the Old Akkadian period he could also be depicted alongside his Lahmu servants, divinities represented as naked or kilted male figures with abundant facial hair and locks of hair on each side of their face.[96] On cylinder seals they could be represented as his doorkeepers, holding a gate-post, or in later periods a spade.[97] Another figure closely associated with Ea in pictorial representations is the fish-man, who has the upper body of a man and the lower body of a fish. It was depicted next to symbols of Ea.[98] It is attested in pictorial representations from the Neo Sumerian period up until Hellenistic times, and might have been the precursor of the merman in Greek and Medieval European art and literature.[99][92]

In Akkadian period seals, Ea was depicted in various scenes, some of which likely have a mythological background. A well known example is the seal of Adda.[100][101] There he is depicted with one foot on a mountain, with water streams coming out of his shoulders, and fish swimming in them. An ibex or a bull is seated beneath his right foot. An eagle descends from above to the center of the scene. Ea’s two faced vizier stands behind him. The god rising from the mountain is most often interpreted as Shamash, though Adad or Ninurta have also been proposed, and the armed goddess as Ishtar.[102][2] Another well attested example is a motif where a half man, half bird creature is presented before an enthroned Ea by one or two gods, one of which is generally Isimud.[103] Various interpretations of these scenes have been proposed by scholars.[104] Pierre Amiet proposed that the scene on the Adda cylinder may represent the revelation of the forces of nature in early spring.[105] Kramer and Maier proposed that the scene of the ‘’bird-man’’ led before the god of streams could be derived from the Anzû myth, representing the return of the tablets of destinies to Enki after the defeat of the Anzû bird who had stolen them,[106] as in the sumerian version of the myth he was their guardian, while in the akkadian version they were stolen from Enlil instead.[93][107] However, since only a few, difficult to understand myths are preserved from the period, the narrative behind the scenes remains uncertain.[108] Ea could also be depicted travelling on his boat. According to one text, the name of the boat was ‘’Ibex of the Abzû’’[93]. Enki’s association with the ibex dates to the second half of the third millennium.[109]

The little owl is called the bird of Ea in the Bird Call Text.[110]

-

Akkadian cylinder seal depicting Ea travelling on his boat.

-

Akkadian cylinder seal depicting four deities stepping before the enthroned Ea.

-

Cylinder seal representing Ea alongside Lahmu.

Worship

[edit]The main temple to Enki was called E-abzu, meaning "abzu temple" (also E-en-gur-a, meaning "house of the subterranean waters"), a ziggurat temple surrounded by Euphratean marshlands near the ancient Persian Gulf coastline at Eridu. It was the first temple known to have been built in Southern Iraq. Four separate excavations at the site of Eridu have demonstrated the existence of a shrine dating back to the earliest Ubaid period, more than 6,500 years ago. Over the following 4,500 years, the temple was expanded 18 times, until it was abandoned during the Persian period.[111][page needed] On this basis Thorkild Jacobsen[112] has hypothesized that the original deity of the temple was Abzu, with his attributes later being taken by Enki over time. P. Steinkeller believes that, during the earliest period, Enki had a subordinate position to a goddess (possibly Ninhursag), taking the role of divine consort or high priest,[113] later taking priority. The Enki temple had at its entrance a pool of fresh water, and excavation has found numerous carp bones, suggesting collective feasts. Carp are shown in the twin water flows running into the later God Enki, suggesting continuity of these features over a very long period. These features were found at all subsequent Sumerian temples, suggesting that this temple established the pattern for all subsequent Sumerian temples. "All rules laid down at Eridu were faithfully observed".[114]

Mythology

[edit]

Creation of life and sickness

[edit]The cosmogenic myth common in Sumer was that of the hieros gamos, a sacred marriage where divine principles in the form of dualistic opposites came together as male and female to give birth to the cosmos. In the epic Enki and Ninhursag, Enki, as lord of Ab or fresh water, is living with his wife in the paradise of Dilmun where

The land of Dilmun is a pure place, the land of Dilmun is a clean place,

The land of Dilmun is a clean place, the land of Dilmun is a bright place;

He who is alone laid himself down in Dilmun,

The place, after Enki is clean, that place is bright.

Despite being a place where "the raven uttered no cries" and "the lion killed not, the wolf snatched not the lamb, unknown was the kid-killing dog, unknown was the grain devouring boar", Dilmun had no water and Enki heard the cries of its goddess, Ninsikil, and orders the sun-god Utu to bring fresh water from the Earth for Dilmun. As a result,

Her City Drinks the Water of Abundance,

Dilmun Drinks the Water of Abundance,

Her wells of bitter water, behold they are become wells of good water,

Her fields and farms produced crops and grain,

Her city, behold it has become the house of the banks and quays of the land.

Dilmun was identified with Bahrain, whose name in Arabic means "two seas", where the fresh waters of the Arabian aquifer mingle with the salt waters of the Persian Gulf. This mingling of waters was known in Sumerian as Nammu, and was identified as the mother of Enki.

The subsequent tale, with similarities to the Biblical story of the forbidden fruit, repeats the story of how fresh water brings life to a barren land.[118] Enki, the Water-Lord then "caused to flow the 'water of the heart" and having fertilised his consort Ninhursag, also known as Ki or Earth, after "Nine days being her nine months, the months of 'womanhood'... like good butter, Nintu, the mother of the land, ...like good butter, gave birth to Ninsar, (Lady Greenery)". When Ninhursag left him, as Water-Lord he came upon Ninsar (Lady Greenery). Not knowing her to be his daughter, and because she reminds him of his absent consort, Enki then seduces and has intercourse with her. Ninsar then gave birth to Ninkurra (Lady Fruitfulness or Lady Pasture), and leaves Enki alone again. A second time, Enki, in his loneliness finds and seduces Ninkurra, and from the union Ninkurra gave birth to Uttu (weaver or spider, the weaver of the web of life).

A third time Enki succumbs to temptation, and attempts seduction of Uttu. Upset about Enki's reputation, Uttu consults Ninhursag, who, upset at the promiscuous wayward nature of her spouse, advises Uttu to avoid the riverbanks, the places likely to be affected by flooding, the home of Enki. In another version of this myth, Ninhursag takes Enki's semen from Uttu's womb and plants it in the earth where eight plants rapidly germinate. With his two-faced servant and steward Isimud, "Enki, in the swampland, in the swampland lies stretched out, 'What is this (plant), what is this (plant).' His messenger Isimud, answers him; 'My king, this is the tree-plant', he says to him. He cuts it off for him and he (Enki) eats it". And so, despite warnings, Enki consumes the other seven fruit. Consuming his own semen, he falls pregnant (ill with swellings) in his jaw, his teeth, his mouth, his hip, his throat, his limbs, his side and his rib. The gods are at a loss to know what to do; chagrined they "sit in the dust". As Enki lacks a birth canal through which to give birth, he seems to be dying with swellings. The fox then asks Enlil, King of the Gods, "If I bring Ninhursag before thee, what shall be my reward?" Ninhursag's sacred fox then fetches the goddess.

Ninhursag relents and takes Enki's Ab (water, or semen) into her body, and gives birth to gods of healing of each part of the body: Abu for the jaw, Nanshe for the throat, Nintul for the hip, Ninsutu for the tooth, Ninkasi for the mouth, Dazimua for the side, Enshagag for the limbs. The last one, Ninti (Lady Rib), is also a pun on Lady Life, a title of Ninhursag herself. The story thus symbolically reflects the way in which life is brought forth through the addition of water to the land, and once it grows, water is required to bring plants to fruit. It also counsels balance and responsibility, nothing to excess.

Ninti, the title of Ninhursag, also means "the mother of all living", and was a title later given to the Hurrian goddess Kheba. This is also the title given in the Bible to Eve, the Hebrew and Aramaic Ḥawwah (חוה), who was made from the rib of Adam, in a strange reflection of the Sumerian myth, in which Adam – not Enki – walks in the Garden of Paradise.[119][page needed]

Making of man

[edit]After six generations of gods, in the Babylonian Enûma Eliš, in the seventh generation, (Akkadian "shapattu" or sabath), the younger Igigi gods, the sons and daughters of Enlil and Ninlil, go on strike and refuse their duties of keeping creation working. Abzu, god of fresh water, co-creator of the cosmos, threatens to destroy the world with his waters, and the gods gather in terror. Enki promises to help and puts Abzu to sleep, confining him in irrigation canals and places him in the Kur, beneath his city of Eridu. But the universe is still threatened, as Tiamat, angry at the imprisonment of Abzu and at the prompting of her son and vizier Kingu, decides to take back creation herself. The gods gather again in terror and turn to Enki for help, but Enki – who harnessed Abzu, Tiamat's consort, for irrigation – refuses to get involved. The gods then seek help elsewhere, and the patriarchal Enlil, their father, god of Nippur, promises to solve the problem if they make him King of the Gods. In the Babylonian tale, Enlil's role is taken by Marduk, Enki's son, and in the Assyrian version it is Ashur. After dispatching Tiamat with the "arrows of his winds" down her throat and constructing the heavens with the arch of her ribs, Enlil places her tail in the sky as the Milky Way, and her crying eyes become the source of the Tigris and Euphrates. But there is still the problem of "who will keep the cosmos working". Enki, who might have otherwise come to their aid, is lying in a deep sleep and fails to hear their cries. His mother Nammu (creatrix also of Abzu and Tiamat) "brings the tears of the gods" before Enki and says

Oh my son, arise from thy bed, from thy (slumber), work what is wise,

Fashion servants for the Gods, may they produce their (bread?).

Enki then advises that they create a servant of the gods, humankind, out of clay and blood.[120] Against Enki's wish, the gods decide to slay Kingu, and Enki finally consents to use Kingu's blood to make the first human, with whom Enki always later has a close relationship, the first of the seven sages, seven wise men or "Abgallu" (ab = water, gal = great, lu = man), also known as Adapa. Enki assembles a team of divinities to help him, creating a host of "good and princely fashioners". He tells his mother:

Oh my mother, the creature whose name thou has uttered, it exists,

Bind upon it the (will?) of the Gods;

Mix the heart of clay that is over the Abyss,

The good and princely fashioners will thicken the clay

Thou, do thou bring the limbs into existence;

Ninmah (Ninhursag, his wife and consort) will work above thee

(Nintu?) (goddess of birth) will stand by thy fashioning;

Oh my mother, decree thou its (the new born's) fate.

Adapa, the first man fashioned, later goes and acts as the advisor to the King of Eridu, when in the Sumerian King-List, the me of "kingship descends on Eridu".

Samuel Noah Kramer believes that behind this myth of Enki's confinement of Abzu lies an older one of the struggle between Enki and the Dragon Kur (the underworld).[119][page needed]

The Atrahasis-Epos has it that Enlil requested from Nammu the creation of humans. And Nammu told him that with the help of Enki (her son) she can create humans in the image of gods.

Uniter of languages

[edit]In the Sumerian epic entitled Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta, in a speech of Enmerkar, an introductory spell appears, recounting Enki having had mankind communicate in one language (following Jay Crisostomo 2019); in other accounts, it is a hymn imploring Enki to do so. In either case, Enki "facilitated the debates between [the two kings] by allowing the world to speak one language," the presumed superior language of the tablet, i.e. Sumerian.[note 1]

Jay Crisostomo's 2019 translation, based on the recent work of C. Mittermayer is:

At that time, as there was no snake, as there was no scorpion,

as there was no hyena, as there was no lion,

as there was no dog or wolf, as there was no fear or trembling

— as humans had no rival.

It was then that the lands of Subur [and] Hamazi,

the distinctly-tongued, Sumer, the great mountain, the essence of nobility,

Akkad, the land possessing the befitting,

and the land of Martu, lying in safety

— the totality of heaven and earth, the well-guarded people, [all] proclaimed Enlil in a single language.

Enki, the lord of abundance and true word,

the lord chosen in wisdom who watches over the land,

the expert of all the gods, the chosen in wisdom,

the lord of Eridu, [Enki] placed an alteration of the language in their mouths.

The speech of humanity is one.

S.N. Kramer's 1940 translation is as follows:[note 2]

Once upon a time there was no snake, there was no scorpion,

There was no hyena, there was no lion,

There was no wild dog, no wolf,

There was no fear, no terror,

Man had no rival.

In those days, the lands of Subur (and) Hamazi,

Harmony-tongued Sumer, the great land of the decrees of princeship,

Uri, the land having all that is appropriate,

The land Martu, resting in security,

The whole universe, the people in unison

To Enlil in one tongue [spoke].

(Then) Enki, the lord of abundance (whose) commands are trustworthy,

The lord of wisdom, who understands the land,

The leader of the gods,

Endowed with wisdom, the lord of Eridu

Changed the speech in their mouths, [brought] contention into it,

Into the speech of man that (until then) had been one.

The deluge

[edit]In the Sumerian version of the flood myth, the causes of the flood and the reasons for the hero's survival are unknown due to the fact that the beginning of the tablet describing the story has been destroyed. Nonetheless, Kramer has stated that it can probably be reasonably inferred that the hero Ziusudra survives due to Enki's aid because that is what happens in the later Akkadian and Babylonian versions of the story.[119]: 97–99

In the later Legend of Atrahasis, Enlil, the King of the Gods, sets out to eliminate humanity, whose noise is disturbing his rest. He successively sends drought, famine and plague to eliminate humanity, but Enki thwarts his half-brother's plans by teaching Atrahasis how to counter these threats. Each time, Atrahasis asks the population to abandon worship of all gods except the one responsible for the calamity, and this seems to shame them into relenting. Humans, however, proliferate a fourth time. Enraged, Enlil convenes a Council of Deities and gets them to promise not to tell humankind that he plans their total annihilation. Enki does not tell Atrahasis directly, but speaks to him in secret via a reed wall. He instructs Atrahasis to build a boat in order to rescue his family and other living creatures from the coming deluge. After the seven-day deluge, the flood hero frees a swallow, a raven and a dove in an effort to find if the flood waters have receded. Upon landing, a sacrifice is made to the gods. Enlil is angry his will has been thwarted yet again, and Enki is named as the culprit. Enki explains that Enlil is unfair to punish the guiltless, and the gods institute measures to ensure that humanity does not become too populous in the future. This is one of the oldest of the surviving Middle Eastern deluge myths.

Enki and Inanna

[edit]The myth Enki and Inanna[125][126] tells the story of how the young goddess of the É-anna temple of Uruk feasts with her father Enki.[127] The two deities participate in a drinking competition; then, Enki, thoroughly inebriated, gives Inanna all of the mes. The next morning, when Enki awakes with a hangover, he asks his servant Isimud for the mes, only to be informed that he has given them to Inanna. Upset, he sends Galla to recover them. Inanna sails away in the boat of heaven and arrives safely back at the quay of Uruk. Eventually, Enki admits his defeat and accepts a peace treaty with Uruk.

Politically, this myth would seem to indicate events of an early period when political authority passed from Enki's city of Eridu to Inanna's city of Uruk.

In the myth of Inanna's Descent,[126] Inanna, in order to console her grieving sister Ereshkigal, who is mourning the death of her husband Gugalana (gu 'bull', gal 'big', ana 'sky/heaven'), slain by Gilgamesh and Enkidu, sets out to visit her sister. Inanna tells her servant Ninshubur ('Lady Evening', a reference to Inanna's role as the evening star) to get help from Anu, Enlil or Enki if she does not return in three days. After Inanna has not come back, Ninshubur approaches Anu, only to be told that he knows the goddess's strength and her ability to take care of herself. While Enlil tells Ninshubur he is busy running the cosmos, Enki immediately expresses concern and dispatches his Galla (Galaturra or Kurgarra, sexless beings created from the dirt from beneath the god's finger-nails) to recover the young goddess. These beings may be the origin of the Greco-Roman Galli, androgynous beings of the third sex who played an important part in early religious ritual.[128]

In the story Inanna and Shukaletuda,[129] Shukaletuda, the gardener, set by Enki to care for the date palm he had created, finds Inanna sleeping under the palm tree and rapes the goddess in her sleep. Awaking, she discovers that she has been violated and seeks to punish the miscreant. Shukaletuda seeks protection from Enki, whom Bottéro believes to be his father.[130] In classic Enkian fashion, the father advises Shukaletuda to hide in the city where Inanna will not be able to find him. Enki, as the protector of whoever comes to seek his help, and as the empowerer of Inanna, here challenges the young impetuous goddess to control her anger so as to be better able to function as a great judge.

Eventually, after cooling her anger, she too seeks the help of Enki, as spokesperson of the "assembly of the gods", the Igigi and the Anunnaki. After she presents her case, Enki sees that justice needs to be done and promises help, delivering knowledge of where the miscreant is hiding.

Influence

[edit]

Enki and later Ea were apparently depicted, sometimes, as a man covered with the skin of a fish, and this representation, as likewise the name of his temple E-apsu, "house of the watery deep", points decidedly to his original character as a god of the waters (see Oannes). Around the excavation of the 18 shrines found on the spot, thousands of carp bones were found, consumed possibly in feasts to the god. Of his cult at Eridu, which goes back to the oldest period of Mesopotamian history, nothing definite is known except that his temple was also associated with Ninhursag's temple which was called Esaggila, "the lofty head house" (E, house, sag, head, ila, high; or Akkadian goddess = Ila), a name shared with Marduk's temple in Babylon, pointing to a staged tower or ziggurat (as with the temple of Enlil at Nippur, which was known as E-kur (kur, hill)), and that incantations, involving ceremonial rites in which water as a sacred element played a prominent part, formed a feature of his worship. This seems also implicated in the epic of the hieros gamos or sacred marriage of Enki and Ninhursag (above), which seems an etiological myth of the fertilisation of the dry ground by the coming of irrigation water (from Sumerian a, ab, water or semen). The early inscriptions of Urukagina in fact go so far as to suggest that the divine pair, Enki and Ninki, were the progenitors of seven pairs of gods, including Enki as god of Eridu, Enlil of Nippur, and Su'en (or Sin) of Ur, and were themselves the children of An (sky, heaven) and Ki (earth).[111][page needed] The pool of the Abzu at the front of his temple was adopted also at the temple to Nanna (Akkadian Sin) the Moon, at Ur, and spread from there throughout the Middle East. It is believed to remain today as the sacred pool at Mosques, or as the holy water font in Catholic or Eastern Orthodox churches.[130][page needed]

Whether Eridu at one time also played an important political role in Sumerian affairs is not certain, though not improbable. At all events the prominence of "Ea" led, as in the case of Nippur, to the survival of Eridu as a sacred city, long after it had ceased to have any significance as a political center. Myths in which Ea figures prominently have been found in Assurbanipal's library, and in the Hattusas archive in Hittite Anatolia. As Ea, Enki had a wide influence outside of Sumer, being equated with El (at Ugarit) and possibly Yah (at Ebla) in the Canaanite 'ilhm pantheon. He is also found in Hurrian and Hittite mythology as a god of contracts, and is particularly favourable to humankind. It has been suggested that etymologically the name Ea comes from the term *hyy (life), referring to Enki's waters as life-giving.[131] Enki/Ea is essentially a god of civilization, wisdom, and culture. He was also the creator and protector of man, and of the world in general. Traces of this version of Ea appear in the Marduk epic celebrating the achievements of this god and the close connection between the Ea cult at Eridu and that of Marduk. The correlation between the two rises from two other important connections: (1) that the name of Marduk's sanctuary at Babylon bears the same name, Esaggila, as that of a temple in Eridu, and (2) that Marduk is generally termed the son of Ea, who derives his powers from the voluntary abdication of the father in favour of his son. Accordingly, the incantations originally composed for the Ea cult were re-edited by the priests of Babylon and adapted to the worship of Marduk, and, similarly, the hymns to Marduk betray traces of the transfer to Marduk of attributes which originally belonged to Ea.

It is, however, as the third figure in the triad (the two other members of which were Anu and Enlil) that Ea acquires his permanent place in the pantheon. To him was assigned the control of the watery element, and in this capacity he becomes the shar apsi; i.e. king of the Apsu or "the abyss". The Apsu was figured as the abyss of water beneath the earth, and since the gathering place of the dead, known as Aralu, was situated near the confines of the Apsu, he was also designated as En -Ki; i.e. "lord of that which is below", in contrast to Anu, who was the lord of the "above" or the heavens. The cult of Ea extended throughout Babylonia and Assyria. We find temples and shrines erected in his honour, e.g. at Nippur, Girsu, Ur, Babylon, Sippar, and Nineveh, and the numerous epithets given to him, as well as the various forms under which the god appears, alike bear witness to the popularity which he enjoyed from the earliest to the latest period of Babylonian-Assyrian history. The consort of Ea, known as Ninhursag, Ki, Uriash Damkina, "lady of that which is below", or Damgalnunna, "big lady of the waters", originally was fully equal with Ea, but in more patriarchal Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian times plays a part merely in association with her lord. Generally, however, Enki seems to be a reflection of pre-patriarchal times, in which relations between the sexes were characterised by a situation of greater gender equality. In his character, he prefers persuasion to conflict, which he seeks to avoid if possible.

Ea and West Semitic deities

[edit]In 1964, a team of Italian archaeologists under the direction of Paolo Matthiae of the University of Rome La Sapienza performed a series of excavations of material from the third-millennium BCE city of Ebla. Much of the written material found in these digs was later translated by Giovanni Pettinato. Among other conclusions, he found a tendency among the inhabitants of Ebla, after the reign of Sargon of Akkad, to replace the name of El, king of the gods of the Canaanite pantheon (found in names such as Mikael and Ishmael), with Ia (Mikaia, Ishmaia).[132]

Jean Bottéro (1952)[133] and others[134] suggested that Ia in this case is a West Semitic (Canaanite) way of pronouncing the Akkadian name Ea. Scholars largely reject the theory identifying this Ia with the Israelite theonym YHWH,[135] while explaining how it might have been misinterpreted.[136] Ia has also been compared by William Hallo with the Ugaritic god Yamm ("Sea"), (also called Judge Nahar, or Judge River) whose earlier name in at least one ancient source was Yaw or Ya'a[failed verification].[clarification needed][137]

Ea was also known as Dagon and Uanna (Grecised Oannes), the first of the Seven Sages.[18]

See also

[edit]- Ancient Near East

- Azazel

- Barbar Temple, a Dilmun-era temple in Bahrain devoted to the worship of Enki

- Capricorn (astrology)

- Capricornus

- Aquarius (astrology)

- Iah

- Jah

- Me (mythology)

- Mesopotamian mythology

- Ahura Mazda

- El (deity)

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ In the larger narrative Enmerkar is the king of Uruk (Sumer) and Aratta is a mythical eastern land. This episode is one of the most-argued in Assyriological literature.[121][122][123]

- ^ Another translation describes 'Hamazi, the many-tongued' and instead calls on Enki to change the languages of mankind into one.[124]

Citations

[edit]- ^ Galter 1983, p. 52-103.

- ^ a b "The Adda Seal". British Museum.

- ^ a b Wiggermann 1997, p. 226.

- ^ a b Seidl 1971, p. 486.

- ^ a b c Black & Green 1992, p. 75.

- ^ Wiggermann 1998, p. 138.

- ^ Lambert 2013, p. 405.

- ^ Krebernik 1997, p. 507.

- ^ Shwemer 2008, p. 133.

- ^ Katz 2008, p. 322.

- ^ Zgoll 1998, p. 352.

- ^ Asher-Greve & Goodnick Westenholz 2013, p. 168.

- ^ a b Tugendhaft 2016, p. 180.

- ^ Garrison 2009, p. 2.

- ^ West 1994, p. 129-149.

- ^ Duchemin 1974, p. 33-67.

- ^ Duke, T. T. (1971). "Ovid's Pyramus and Thisbe". The Classical Journal. 66 (4). Classical Association of the Middle West and South (CAMWS): 320–327. ISSN 0009-8353. JSTOR 3296569. p. 324, note 28: "... Leonard Palmer suggests in his Interpretation of Mycenaean Greek texts (1963), p. 255, that the name of Poseidon is a direct translation of the Sumerian EN.KI, 'lord of the earth'".

- ^ a b Duke, T. T. (1971). "Ovid's Pyramus and Thisbe". The Classical Journal. 66 (4). Classical Association of the Middle West and South (CAMWS): 320–327. ISSN 0009-8353. JSTOR 3296569. p. 324, note 27.

- ^ Langdon, S. (1918). "The Babylonian Conception of the Logos". The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. Cambridge University Press: 433–449 [434]. ISSN 0009-8353. JSTOR 25209408.

- ^ Origins of the ancient constellations: I. The Mesopotamian traditions by J.H. Rogers

- ^ Black & Green 1992, p. 145.

- ^ Foster, Benjamin R. (2007). "4 Mesopotamia". In Hinnells, John R. (ed.). A Handbook of Ancient Religions. Cambridge University Press. p. 174. ISBN 978-1-139-46198-6.

- ^ Black & Green 1992, p. 133.

- ^ Nugent, Tony (1 January 1993). "Star-god: Enki/Ea and the biblical god as expressions of a common ancient Near Eastern astral-theological symbol system". Religion – Dissertations.

- ^ Horry, Ruth (2019). "Enki/Ea (god)". Ancient Mesopotamian Gods and Goddesses. Open Richly Annotated Cuneiform Corpus, UK Higher Education Academy. Retrieved 31 May 2025.

- ^ Archi 2010, p. 15-17.

- ^ a b Galter 1983, p. 8.

- ^ a b Lambert 1989, p. 116.

- ^ a b Kramer 1960, p. 276.

- ^ Galter 1983, p. 8-9.

- ^ Jacobsen 1992, p. 415.

- ^ a b Jacobsen 1976, p. 111.

- ^ Jacobsen 1970, p. 22.

- ^ Espak 2010, p. 237.

- ^ a b Jacobsen 1976, p. 252.

- ^ Lambert 2013, p. 414.

- ^ Lambert 2013, p. 417.

- ^ Espak 2006, p. 27.

- ^ a b Sollberger 1966, p. 141.

- ^ Sollberger & Kupper 1971, p. 301.

- ^ Lisman 2013, p. 128.

- ^ Espak 2006, p. 28.

- ^ Galter 1983, p. 3.

- ^ Roberts 1972, p. 20-21.

- ^ Archi 2010, p. 15.

- ^ Espak 2010, p. 163.

- ^ Civil 1983, p. 44.

- ^ Green 1975, p. 75.

- ^ Weeden 2009, p. 98-103.

- ^ Galter 1983, p. 13.

- ^ a b c Espak 2010, p. 54.

- ^ a b Cavigneaux & Krebernik 1998a, p. 607.

- ^ Espak 2006, p. 41.

- ^ Roberts 1972, p. 80.

- ^ a b Galter 1998, p. 77.

- ^ a b Galter 1998, p. 78.

- ^ a b c Galter 1983, p. 11.

- ^ a b c Galter 1983, p. 12.

- ^ Lambert & Millard 1969, p. 148-149.

- ^ a b Cavigneaux & Krebernik 1998b, p. 590.

- ^ a b Galter 1983, p. 10.

- ^ Galter 1983, p. 10-51.

- ^ a b Galter 1983, p. 32.

- ^ Lambert & Winters 2023, p. 29.

- ^ Galter 1983, p. 51.

- ^ Galter 1983, p. 37.

- ^ Galter 1983, p. 34.

- ^ a b Galter 1983, p. 36.

- ^ Galter 1983, p. 38.

- ^ Galter 1983, p. 40.

- ^ Lambert & Millard 1969, p. 149.

- ^ Galter 1983, p. 15.

- ^ Lambert & Winters 2023, p. 131.

- ^ Galter 1983, p. 26.

- ^ Espak 2010, p. 59.

- ^ Espak 2010, p. 99.

- ^ Galter 1983, p. 45.

- ^ Lisman 2013, p. 131-132.

- ^ Boivin 2018, p. 40.

- ^ Asher-Greve & Goodnick Westenholz 2013, p. 289.

- ^ Lambert 1997, p. 5.

- ^ Boehmer 1965, p. 87.

- ^ Espak 2010, p. 19 note 30.

- ^ Galter 1983, p. 114.

- ^ Galter 1983, p. 115.

- ^ Seidl 1971, p. 488-489.

- ^ Galter 1983, p. 104.

- ^ a b c d Galter 1983, p. 106.

- ^ Black & Green 1992, p. 169.

- ^ Black & Green 1992, p. 93.

- ^ Rogers 1998, p. 27-28.

- ^ a b Green 1997, p. 257.

- ^ a b c Galter 1983, p. 105.

- ^ Seidl 1971, p. 488.

- ^ Black & Green 1992, p. 179.

- ^ Lambert 1997, p. 6.

- ^ Wiggermann 1981, p. 101-102.

- ^ Galter 1983, p. 107.

- ^ Black & Green 1992, p. 131.

- ^ Kramer & Maier 1989, p. 119-121.

- ^ Espak 2006, p. 77.

- ^ Kramer & Maier 1989, p. 122.

- ^ Galter 1983, p. 112.

- ^ Kramer & Maier 1989, p. 121-123.

- ^ Kramer & Maier 1989, p. 123.

- ^ Kramer & Maier 1989, p. 121.

- ^ Green 1997, p. 249.

- ^ Espak 2006, p. 80.

- ^ Lisman 2013, p. 131.

- ^ Galter 1983, p. 108.

- ^ a b Espak 2006.

- ^ Jacobsen, Thorkild (1970) "Mesopotamian Gods and Pantheons", p. 22

- ^ Steinkeller P. (1999) "Priests and Officials", p. 129

- ^ van Buren, E.D. (1951) OsNs 21, p. 293[full citation needed]

- ^ "Cylinder Seal of Ibni-Sharrum". Louvre Museum.

- ^ "Site officiel du musée du Louvre". cartelfr.louvre.fr.

- ^ Brown, Brian A.; Feldman, Marian H. (2013). Critical Approaches to Ancient Near Eastern Art. Walter de Gruyter. p. 187. ISBN 978-1-61451-035-2.

- ^ "Enki and Ninhursaja". Line 50–87. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ^ a b c Kramer, Samuel Noah (1961). Sumerian Mythology: A Study of Spiritual and Literary Achievement in the Third Millennium B.C.. New York: Harper & Brothers. ISBN 0-8122-1047-6.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Kramer 1963, pp. 149–151; Kramer 1961, pp. 69–72; Christopher B. Siren (1999) based on John C. Gibson's Canaanite Mythology and S. H. Hooke's Middle Eastern Mythology

- ^ Crisostomo, Translation as Scholarship: Language, Writing, and Bilingual Education in Ancient Babylonia (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2019), 36–39. ISBN 978-1-5015-0981-0

- ^ Jacob Klein, "The So-called 'Spell of Nudimmud' (ELA 134–155): A Re-examination", in Simonetta Graziani, ed., Studi sul Vicino Oriente Antico dedicati alla memoria di Luigi Cagni (Naples: Instituto Universitario Orientale, 2000), 563–84

- ^ C. Mittermayer, Enmerkara und der Herr von Arata: ein ungleicher Wettstreit (Freiburg: Academic Press, 2009), 363.

- ^ "Enmerkar and the lord of Aratta: translation". etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- ^ "Inanna: Lady of Love and War, Queen of Heaven and Earth, Morning and Evening Star", consulted 25 August 2007 [1]

- ^ a b Wolkstein, Diane; Kramer, Samuel Noah (1983). Inanna: Queen of Heaven and Earth: Her Stories and Hymns from Sumer. Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0-06-090854-6.

- ^ Echlin, Kim (2015). Inanna: A New English Version. Penguin. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-14-319458-3.

- ^ Enheduanna; Meador, Betty De Shong (2000). Inanna, Lady of Largest Heart: Poems of the Sumerian High Priestess Enheduanna. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-75242-9.

- ^ Lishtar "The Avenging Maiden and the Predator Gardener: a study of Inanna and Shukaletuda" [2]

- ^ a b Bottéro 1992.

- ^ Alfonso Archii (2012). "The God Hay(Y)A (Ea / Enki) At Ebla". In Melville, Sarah; Slotsky, Alice (eds.). Opening the Tablet Box: Near Eastern Studies in Honor of Benjamin R. Foste. Brill. pp. 15–16, 25. ISBN 978-90-04-18652-1. Retrieved 19 June 2014.

- ^ Freeman, Tzvi. "Is there evidence of Abraham's revolution? – The Big Picture". Chabad.org. Retrieved 2011-06-06.

- ^ Bottero, Jean. "Religion in Ancient Mesopotamia" (University of Chicago Press, 2004) ISBN 0-226-06718-1

- ^ Boboula, Ida. "The Great Stag: A Sumerian Deity and Its Affiliations", Fifty-Third General Meeting of the Archaeological Institute of America (1951) in American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 56, No. 3 (Jul. 1952) 171–178, JSTOR 500533

- ^ Watson E. Mills; Roger Aubrey Bullard (1990). Mercer Dictionary of the Bible. Mercer University Press. p. 226. ISBN 9780865543737.

- ^ "Yahweh" in K. van der Toorn, Bob Becking, Pieter Willem van der Horst, Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible (1999), ISBN 978-90-04-11119-6, p. 911: "his cult at Ebla is a chimera."

- ^ Hallo, William W. (April–June 1996). "Review: Enki and the Theology of Eridu". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 116 (2): 231–34. doi:10.2307/605698. JSTOR 605698.

Bibliography

[edit]- Horry, Ruth (2019), "Enki/Ea (god)", Ancient Mesopotamian Gods and Goddesses, Open Richly Annotated Cuneiform Corpus, UK Higher Education Academy

- Galter, Hannes D. (1983). Der Gott Ea/Enki in der akkadischen Überlieferung: eine Bestandsaufnahme des vorhandenen Materials. Dissertationen der Universität Graz (in German). Graz: dbv-Verl. für die Techn. Univ. ISBN 978-3-7041-9018-5.

- Kramer, Samuel Noah; Maier, John R. (1989). Myths of Enki, the Crafty God. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9781725282896.

- Green, Margaret W. (1975). Eridu in Sumerian literature (PhD thesis). University of Chicago.

- Archi, Alfonso (2010). "The god Hay(y)a (Ea/Enki) at Ebla". In Melville, Sarah C.; Slotsky, Alice L. (eds.). Opening the Tablet Box : Near Eastern Studies in honor of Benjamin R. Foster. Brill Academic Pub. ISBN 978-9004186521.

- Roberts, Jimmy J.M. (1972). The earliest semitic pantheon; a study of the Semitic deities attested in Mesopotamia before Ur III. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 9780801813887.

- Cavigneaux, Antoine; Krebernik, Manfred (1998a), "Nudimmud, Nadimmud", Reallexikon der Assyriologie (in German), retrieved 24 May 2025

- Galter, Hannes D. (1998), "Nagbu", Reallexikon der Assyriologie (in German), retrieved 24 May 2025

- Cavigneaux, Antoine; Krebernik, Manfred (1998b), "Niššīku", Reallexikon der Assyriologie (in German), retrieved 24 May 2025

- Civil, Miguel (1983). "Enlil and Ninlil: The Marriage of Sud". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 103 (1). JSTOR 601859.

- Lambert, Wilfred G.; Millard, Alan R. (1969). Atra-Ḫasīs: the Babylonian story of the Flood. Oxford: Clarendon. ISBN 9780198131533.

- Lambert, Wilfred G. (1989). "Reviewed Work: Eblaitica: Essays on the Ebla Archives and Eblaite Language. Vol. I by Cyrus H. Gordon, Gary A. Rendsburg, Nathan H. Winter". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. 52 (1). JSTOR 617916.

- Lambert, Wilfred G. (2013). Babylonian Creation Myths. Eisenbraums. ISBN 9781575062471.

- Lambert, Wilfred G.; Winters, Ryan D. (2023). George, Andrew; Krebernik, Manfred (eds.). An = Anum and Related Lists: God Lists of Ancient Mesopotamia. Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 9783161613821.

- Lisman, Jan W. (2013). Cosmogony, Theogony and Anthropogeny in Sumerian texts. Ugarit-Verlag. ISBN 9783868350951.

- Sollberger, Edmond (1966). The Business and Administrative Correspondence under the Kings of Ur. Locust Valley: J.J. Augustin.

- Sollberger, Edmond; Kupper, Jean-Robert (1971). Inscriptions royales sumériennes et akkadiennes. Paris: CERF.

- Jacobsen, Thorkild (1992). "The Spell of Nudimmud". In Fishbane, Michael; Tov, Emanuel (eds.). Sha'arei Talmon Studies in the Bible, Qumran, and the Ancient Near East Presented to Shemaryahu Talmon. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-0931464614.

- Jacobsen, Thorkild (1976). The Treasures Of Darkness : A History Of Mesopotamian Religion. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300022919.

- Jacobsen, Thorkild (1970). Toward the Image of Tammuz and Other Essays on Mesopotamian History and Culture. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674898103.

- Boivin, Odette (2018). The first dynasty of the Sealand in Mesopotamia. Boston: De Gruyter. ISBN 9781501516399.

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (1960). "Sumero-Akkadian Interconnections: Religious Ideas". Genava. 8. ISSN 0072-0585.

- Bottéro, Jean (1992). Mesopotamia : writing, reasoning, and the gods (1st paperback ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-06727-8.

- Bottéro, Jean (2001). Religion in ancient Mesopotamia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-06718-1.

- Espak, Peeter (2010), "The God Enki in Sumerian Royal Ideology and Mythology", Dissertationes Theologiae Universitatis Tartuensis 19, Tartu University Press, ISBN 9789949195220

- Espak, Peeter (2006). Ancient Near Eastern Gods Ea and Enki; Diachronical analysis of texts and images from the earliest sources to the Neo-Sumerian period (master thesis). Tartu University, Faculty of Theology, Chair for Ancient Near Eastern Studies.

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (1963). The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-45238-7.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Weeden, Mark (2009), "The Akkadian Words for "Grain" and the God Ḫaya", Die Welt des Orients, vol. 36, no. 1, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht (GmbH & Co. KG)

- Lambert, Wilfred G. (1997). "Sumerian Gods: Combining the Evidence of Texts and Art". In Finkel, Irving L.; Geller, Markham J. (eds.). Sumerian gods and their representations. Groningen: Styx Publications. ISBN 978-9056930059.

- Wiggermann, F.A.M (1997), "Mischwesen A. Philologisch. Mesopotamien · Hybrid creatures A. Philological. In Mesopotamia.", Reallexikon der Assyriologie, retrieved 7 June 2025

- Green, Anthony (1997), "Mischwesen B. Archäologie. Mesopotamien · Hybrid creatures B. Archaeological. In Mesopotamia", Reallexikon der Assyriologie, retrieved 7 June 2025

- Seidl, Ursula (1971), "Göttersymbole und attribute A. I. Archäologisch. Mesopotamien · Divine symbol and attributes A. I. Archaeological. Mesopotamia", Reallexikon der Assyriologie (in German), retrieved 7 June 2025

- Zgoll, Annette (1998), "Ningal A. I. In Mesopotamien · Ningal A. I. In Mesopotamia", Reallexikon der Assyriologie, retrieved 7 June 2025

- Boehmer, Rainer Michael (1965). Die Entwicklung der Glyptik während der Akkad-Zeit. Berlin: De Gruyter. ISBN 9783110001013.

- Black, Jeremy; Green, Anthony (1992). Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0292707948.

- Wiggermann, F.A.M. (1981), "Exit Talim! Studies in Babylonian Demonology, I", Jaarbericht van het Vooraziatisch-Egyptisch Genootschap Ex Oriente Lux, no. 27

- Rogers, John H. (1998), "Origins of the ancient constellations: I. The Mesopotamian traditions", Journal of the British Astronomical Association, vol. 108, no. 1

- West, Stephanie (1994), "Prometheus Orientalized", Museum Helveticum, vol. 51, no. 3, pp. 129–149, JSTOR 24818292

- Duchemin, Jacqueline (1974). Prométhée, Histoire du mythe, de ses origines orientales à ses incarnations modernes. Paris: Les Belles Lettres. ISBN 9782251324326.

- Caduff, Gian Andrea (1986), Antike Sintflutsagen, Hypomnemata. Untersuchungen zur Antike und zu ihrem Nachleben, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht

- Garrison, Mark B. (2009), "God on serpent throne" (PDF), Iconography of Deities and Demons in the Ancient Near East, Swiss National Science Foundation, retrieved 7 June 2025

- Katz, Dina (1 January 2008), "Enki and Ninhursaga, Part Two", Bibliotheca Orientalis, vol. 65, no. 3

- Wiggermann, F.A.M. (1998), "Nammu", Reallexikon der Assyriologie, retrieved 7 June 2025

- Shwemer, Daniel (2008), "The Storm-Gods of the Ancient Near East: Summary, Synthesis, Recent Studies. Part I", Journal of Ancient Near Eastern Religions, vol. 7, no. 2

- Krebernik, Manfred (1997), "Muttergöttin A. I. In Mesopotamien", Reallexikon der Assyriologie (in German), retrieved 7 June 2025

- Tugendhaft, Aaron (2016). "Gods on clay: Ancient Near Eastern scholarly practices and the history of religions". In Grafton, Anthony; Most, Glenn W. (eds.). Canonical Texts and Scholarly Practices A Global Comparative Approach. Cambridge University Press.

- Asher-Greve, Julia M.; Goodnick Westenholz, Joan (2013). Goddesses in Context: On Divine Powers, Roles, Relationships and Gender in Mesopotamian Textual and Visual Sources (PDF). Göttingen: Academic Press.