Prolactin

Prolactin (PRL), also known as lactotropin and mammotropin, is a protein best known for its role in enabling mammals to produce milk. It is influential in over 300 separate processes in various vertebrates, including humans.[5] Prolactin is secreted from the pituitary gland in response to eating, mating, estrogen treatment, ovulation and nursing. It is secreted heavily in pulses in between these events. Prolactin plays an essential role in metabolism, regulation of the immune system and pancreatic development.[6][7]

Discovered in non-human animals around 1930 by Oscar Riddle[8] and confirmed in humans in 1970 by Henry Friesen,[9] prolactin is a peptide hormone, encoded by the PRL gene.[10]

In mammals, prolactin is associated with milk production; in fish it is thought to be related to the control of water and salt balance. Prolactin also acts in a cytokine-like manner and as an important regulator of the immune system. It has important cell cycle-related functions as a growth-, differentiating- and anti-apoptotic factor. As a growth factor, binding to cytokine-like receptors, it influences hematopoiesis and angiogenesis and is involved in the regulation of blood clotting through several pathways. The hormone acts in endocrine, autocrine, and paracrine manners through the prolactin receptor and numerous cytokine receptors.[5]

Pituitary prolactin secretion is regulated by endocrine neurons in the hypothalamus. The most important of these are the neurosecretory tuberoinfundibulum (TIDA) neurons of the arcuate nucleus that secrete dopamine (a.k.a. Prolactin Inhibitory Hormone) to act on the D2 receptors of lactotrophs, causing inhibition of prolactin secretion. Thyrotropin-releasing hormone has a stimulatory effect on prolactin release, although prolactin is the only anterior pituitary hormone whose principal control is inhibitory.

Several variants and forms are known per species. Many fish have variants prolactin A and prolactin B. Most vertebrates, including humans, also have the closely related somatolactin. In humans, 14, 16, and 22 kDa variants exist.[11]

Function

[edit]In humans

[edit]Prolactin has a wide variety of effects. It stimulates the mammary glands to produce milk (lactation): increased serum concentrations of prolactin during pregnancy cause enlargement of the mammary glands and prepare for milk production, which normally starts when levels of progesterone fall by the end of pregnancy and a suckling stimulus is present. Prolactin plays an important role in maternal behavior.[12]

It has been shown in rats and sheep that prolactin affects lipid synthesis differentially in mammary and adipose cells. Prolactin deficiency induced by bromocriptine increased lipogenesis and insulin responsiveness in adipocytes while decreasing them in the mammary gland.[13]

In general, dopamine inhibits prolactin[14] but this process has feedback mechanisms.[15]

Elevated levels of prolactin decrease the levels of sex hormones—estrogen in women and testosterone in men.[16] The effects of mildly elevated levels of prolactin are much more variable, in women, substantially increasing or decreasing estrogen levels.

Prolactin is sometimes classified as a gonadotropin[17] although in humans it has only a weak luteotropic effect while the effect of suppressing classical gonadotropic hormones is more important.[18] Prolactin within the normal reference ranges can act as a weak gonadotropin, but at the same time suppresses gonadotropin-releasing hormone secretion. The exact mechanism by which it inhibits gonadotropin-releasing hormone is poorly understood. Although expression of prolactin receptors have been demonstrated in rat hypothalamus, the same has not been observed in gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons.[19] Physiologic levels of prolactin in males enhance luteinizing hormone-receptors in Leydig cells, resulting in testosterone secretion, which leads to spermatogenesis.[20]

Prolactin also stimulates proliferation of oligodendrocyte precursor cells. These cells differentiate into oligodendrocytes, the cells responsible for the formation of myelin coatings on axons in the central nervous system.[21]

Other actions include contributing to pulmonary surfactant synthesis of the fetal lungs at the end of the pregnancy and immune tolerance of the fetus by the maternal organism during pregnancy. Prolactin promotes neurogenesis in maternal and fetal brains.[22][23]

In music psychology, it is conjectured that prolactin may play a role in the pleasurable perception of sad music, as the levels of the hormone increase when a person feels sad, producing a consoling psychological effect.[24]

In other vertebrates

[edit]The primary function of prolactin in fish is osmoregulation,[25] i.e., controlling the movement of water and salts between the tissues of the fish and the surrounding water. Like mammals, however, prolactin in fish also has reproductive functions, including promoting sexual maturation and inducing breeding cycles, as well as brooding and parental care.[26] In the South American discus, prolactin may also regulate the production of a skin secretion that provides food for larval fry.[27] An increase in brooding behaviour caused by prolactin has been reported in hens.[28]

Prolactin and its receptor are expressed in the skin, specifically in the hair follicles, where they regulate hair growth and moulting in an autocrine fashion.[29][30] Elevated levels of prolactin can inhibit hair growth,[31] and knock-out mutations in the prolactin gene cause increased hair length in cattle[32] and mice.[30] Conversely, mutations in the prolactin receptor can cause reduced hair growth, resulting in the "slick" phenotype in cattle.[32][33] Additionally, prolactin delays hair regrowth in mice.[34]

Analogous to its effects on hair growth and shedding in mammals, prolactin in birds controls the moulting of feathers,[35] as well as the age at onset of feathering in both turkeys and chickens.[36] Pigeons, flamingos and male emperor penguins feed their young a cheese-like secretion from the upper digestive tract called crop milk, whose production is regulated by prolactin.[37][38]

In rodents, pseudopregnancy can occur when a female is mated with a sterile male. This mating can cause bi-daily surges of prolactin which would normally occur in rodent pregnancy.[39] Prolactin surges initiate the secretion of progesterone which maintains pregnancy and hence can initiate pseudopregnancy. The false maintenance of pregnancy exhibits the outward physical symptoms of pregnancy, in the absence of a foetus.[40]

Prolactin receptor activation is essential for normal mammary gland development during puberty in mice.[41] Adult virgin female prolactin receptor knockout mice have much smaller and less developed mammary glands than their wild-type counterparts.[41] Prolactin and prolactin receptor signaling are also essential for maturation of the mammary glands during pregnancy in mice.[41]

Regulation

[edit]In humans, prolactin is produced at least in the anterior pituitary, decidua, myometrium, breast, lymphocytes, leukocytes and prostate.[42][43]

Pituitary

[edit]Pituitary prolactin is controlled by the Pit-1 transcription factor, which binds to the gene at several sites including a proximal promoter.[43] This promoter is inhibited by dopamine and stimulated by estrogens, neuropeptides, and growth factors.[44] Estrogens can also suppress dopamine.

Interaction with neuropeptides is still a matter of active research: no specific prolactin-releasing hormone has been identified. It is known that mice react to both VIP and TRH, but humans seem to only react to TRH. There are prolactin-releasing peptides that work in vitro, but whether they deserve their name has been questioned. Oxytocin does not play a large role. Mice without a posterior pituitary do not raise their prolactin levels even with suckling and oxytocin injection, but scientists have yet to identify which specific hormone produced by this region is responsible.[45]

In birds (turkeys), VIP is a powerful prolactin-releasing factor, while peptide histidine isoleucine has almost no effect.[46]

Extrapituitary

[edit]Extrapituitary prolactin is controlled by a superdistal promoter, located 5.8 kb upstream of the pituitary start site. The promoter does not react to dopamine, estrogens, or TRH. Instead, it is stimulated by cAMP. Responsiveness to cAMP is mediated by an imperfect cAMP–responsive element and two CAAT/enhancer binding proteins (C/EBP).[43] Progesterone upregulates prolactin synthesis in the endometrium but decreases it in myometrium and breast glandular tissue.[47]

Breast and other tissues may express the Pit-1 promoter in addition to the distal promoter. Oct-1 appears able to substitute for Pit-1 in activating the promoter in breast cancer cells.[45]

Extrapituitary production of prolactin is thought to be special to humans and primates and may serve mostly tissue-specific paracrine and autocrine purposes. It has been hypothesized that in vertebrates such as mice a similar tissue-specific effect is achieved by a large family of prolactin-like proteins controlled by at least 26 paralogous PRL genes not present in primates.[43]

Stimuli

[edit]Prolactin follows diurnal and ovulatory cycles. Prolactin levels peak during REM sleep and in the early morning. Many mammals experience a seasonal cycle.[38]

During pregnancy, high circulating concentrations of estrogen and progesterone increase prolactin levels by 10- to 20-fold. Estrogen and progesterone inhibit the stimulatory effects of prolactin on milk production. The abrupt drop of estrogen and progesterone levels following delivery allow prolactin—which temporarily remains high—to induce lactation.[48]

Sucking on the nipple offsets the fall in prolactin as the internal stimulus for them is removed. The sucking activates mechanoreceptors in and around the nipple. These signals are carried by nerve fibers through the spinal cord to the hypothalamus, where changes in the electrical activity of neurons that regulate the pituitary gland increase prolactin secretion. The suckling stimulus also triggers the release of oxytocin from the posterior pituitary gland, which triggers milk let-down: Prolactin controls milk production (lactogenesis) but not the milk-ejection reflex; the rise in prolactin fills the breast with milk in preparation for the next feed. The posterior pituitary produces a yet-unidentified hormone that causes prolactin production.[45]

In usual circumstances, in the absence of galactorrhea, lactation ceases within one or two weeks following the end of breastfeeding.

Levels can rise after exercise, high-protein meals, minor surgical procedures,[49] following epileptic seizures[50] or due to physical or emotional stress.[51][52] In a study on female volunteers under hypnosis, prolactin surges resulted from the evocation, with rage, of humiliating experiences, but not from the fantasy of nursing.[52] Stress-induced PRL changes are not linked to the posterior pituitary in rodents.[45]

Hypersecretion is more common than hyposecretion. Hyperprolactinemia is the most frequent abnormality of the anterior pituitary tumors, termed prolactinomas. Prolactinomas may disrupt the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis as prolactin tends to suppress the secretion of gonadotropin-releasing hormone from the hypothalamus and in turn decreases the secretion of follicle-stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone from the anterior pituitary, therefore disrupting the ovulatory cycle.[53] Such hormonal changes may manifest as amenorrhea and infertility in females as well as erectile dysfunction in males.[54][7] Inappropriate lactation (galactorrhoea) is another important clinical sign of prolactinomas.

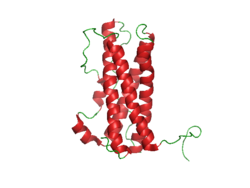

Structure and isoforms

[edit]The structure of prolactin is similar to that of growth hormone and placental lactogen. The molecule is folded due to the activity of three disulfide bonds. Significant heterogeneity of the molecule has been described, thus bioassays and immunoassays can give different results due to differing glycosylation, phosphorylation and sulfation, as well as degradation. The non-glycosylated form of prolactin is the dominant form that is secreted by the pituitary gland.[11]

The three different sizes of prolactin are:

- Little prolactin—the predominant form.[55] It has a molecular weight of approximately 23-kDa.[55] It is a single-chain polypeptide of 199 amino acids and is apparently the result of removal of some amino acids.

- Big prolactin—approximately 48 kDa.[55] It may be the product of interaction of several prolactin molecules. It appears to have little, if any, biological activity.[56]

- Macroprolactin—approximately 150 kDa.[55] It appears to have a low biological activity.[57]

- Other variants with the molecular masses of 14, 16, and 22 kDa.[11]

The levels of larger ones are somewhat higher during the early postpartum period.[58]

Prolactin receptor

[edit]Prolactin receptors are present in the mammillary glands, ovaries, pituitary glands, heart, lung, thymus, spleen, liver, pancreas, kidney, adrenal gland, uterus, skeletal muscle, skin and areas of the central nervous system.[59] When prolactin binds to the receptor, it causes it to dimerize with another prolactin receptor. This results in the activation of Janus kinase 2, a tyrosine kinase that initiates the JAK-STAT pathway. Activation also results in the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases and Src kinase.[59]

Human prolactin receptors are insensitive to mouse prolactin.[60]

Diagnostic use

[edit]Prolactin levels may be checked as part of a sex hormone workup, as elevated prolactin secretion can suppress the secretion of follicle stimulating hormone and gonadotropin-releasing hormone, leading to hypogonadism and sometimes causing erectile dysfunction.[61]

Prolactin levels may be of some use in distinguishing epileptic seizures from psychogenic non-epileptic seizures. The serum prolactin level usually rises following an epileptic seizure.[62]

Units and unit conversions

[edit]The serum concentration of prolactin can be given in mass concentration (μg/L or ng/mL), molar concentration (nmol/L or pmol/L), or international units (typically mIU/L). The current IU is calibrated against the third International Standard for Prolactin, IS 84/500.[63][64] Reference ampoules of IS 84/500 contain "approximately" 2.5 μg of lyophilized human prolactin[65] and have been assigned an activity of 0.053 International Units by calibrating against the previous standard.[63][64] Measurements can be converted into mass units using this ratio of grams to IUs to obtain an equivalent in relationship to the contents of IS 84/500;[66] prolactin concentrations expressed in mIU/L can be converted to μg/L of IS 84/500 equivalent by dividing by 21.2. Previous standards had other ratios in relation to their potency on the assay measurement. For example, the previous IS (83/562) had a potency of 27.0 mIU per μg.[67][68][69][70]

The first International Reference Preparation (or IRP) of human Prolactin for Immunoassay was established in 1978 (75/504 1st IRP for human prolactin) at a time when purified human prolactin was in short supply.[66][67] Previous standards relied on prolactin from animal sources.[70] Purified human prolactin was scarce, heterogeneous, unstable, and difficult to characterize. A preparation labeled 81/541 was distributed by the WHO Expert Committee on Biological Standardization without official status and given the assigned value of 50 mIU/ampoule based on an earlier collaborative study.[66][68] It was determined that this preparation behaved anomalously in certain immunoassays and was not suitable as an IS.[66]

Three different human pituitary extracts containing prolactin were subsequently obtained as candidates for an IS. These were distributed into ampoules coded 83/562, 83/573, and 84/500.[63][64][66][69] Collaborative studies involving 20 different laboratories found little difference between these three preparations. 83/562 appeared to be the most stable. This preparation was largely free of dimers and polymers of prolactin. On the basis of these investigations, 83/562 was established as the Second IS for human prolactin.[69] Once stocks of these ampoules were depleted, 84/500 was established as the Third IS for human prolactin.[63][66]

84/500 has nearly run out and in 2016 replacement was proposed. The new 83/573 contains 67.2 mIU per ampoule when calibrated against the third IS and contains 1.002 g of human pituitary extract each (which is then lyophilized). Each ampoule contains approximately 3.2 μg of prolactin. The assigned value will be 67 mIU per ampoule. If a fifth IS is needed, it will likely be based on recombinant protein, as WHO has not received any further donations of human pituitary extracts.[71]

Reference ranges

[edit]General guidelines for diagnosing prolactin excess (hyperprolactinemia) define the upper threshold of normal prolactin at 25 μg/L for women and 20 μg/L for men.[59] Similarly, guidelines for diagnosing prolactin deficiency (hypoprolactinemia) are defined as prolactin levels below 3 μg/L in women[72][73] and 5 μg/L in men.[74][75][76] However, different assays and methods for measuring prolactin are employed by different laboratories and as such the serum reference range for prolactin is often determined by the laboratory performing the measurement.[59][77] Furthermore, prolactin levels vary according to factors as age,[78] sex,[78] menstrual cycle stage[78] and pregnancy.[78] The circumstances surrounding a given prolactin measurement (assay, patient condition, etc.) must therefore be considered before the measurement can be accurately interpreted.[59]

The following chart illustrates the variations seen in normal prolactin measurements across different populations. Prolactin values were obtained from specific control groups of varying sizes using the IMMULITE assay.[78]

| Proband | Prolactin, μg/L (ng/mL) |

|---|---|

| women, follicular phase (n = 803) | |

| women, luteal phase (n = 699) | |

| women, mid-cycle (n = 53) | |

| women, whole cycle (n = 1555) | |

| women, pregnant, 1st trimester (n = 39) | |

| women, pregnant, 2nd trimester (n = 52) | |

| women, pregnant, 3rd trimester (n = 54) | |

| Men, 21–30 (n = 50) | |

| Men, 31–40 (n = 50) | |

| Men, 41–50 (n = 50) | |

| Men, 51–60 (n = 50) | |

| Men, 61–70 (n = 50) |

Inter-method variability

[edit]The following table illustrates variability in reference ranges of serum prolactin between some commonly used assay methods (as of 2008), using a control group of healthy health care professionals (53 males, age 20–64 years, median 28 years; 97 females, age 19–59 years, median 29 years) in Essex, England:[77]

| Assay method | Mean Prolactin |

Lower limit 2.5th percentile |

Upper limit 97.5th percentile | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mIU/L | μg/L | mIU/L | μg/L | mIU/L | μg/L | |||

| Females | ||||||||

| Centaur | 168 | 7.92 | 71 | 3.35 | 348 | 16.4 | ||

| Immulite | 196 | 9.25 | 75 | 3.54 | 396 | 18.7 | ||

| Access | 192 | 9.06 | 77 | 3.63 | 408 | 19.3 | ||

| Elecsys | 222 | 10.5 | 88 | 4.15 | 492 | 23.2 | ||

| Architect | 225 | 10.6 | 98 | 4.62 | 447 | 21.1 | ||

| AIA[a] | 257 | 9.52 | 105 | 3.89 | 548 | 20.3 | ||

| Males | ||||||||

| Access | 146 | 6.89 | 58 | 2.74 | 277 | 13.1 | ||

| Centaur | 167 | 7.88 | 63 | 2.97 | 262 | 12.4 | ||

| Immulite | 158 | 7.45 | 70 | 3.30 | 281 | 13.3 | ||

| Elecsys | 180 | 8.49 | 72 | 3.40 | 331 | 15.6 | ||

| Architect | 188 | 8.87 | 85 | 4.01 | 310 | 14.6 | ||

| AIA[a] | 211 | 7.81 | 89 | 3.3 | 365 | 13.52 | ||

An example of the use of the above table is, if using the Centaur assay to estimate prolactin values in μg/L for females, the mean is 168 mIU/L (7.92 μg/L) and the reference range is 71–348 mIU/L (3.35–16.4 μg/L).

Conditions

[edit]Elevated levels

[edit]Hyperprolactinaemia, or excess serum prolactin, is associated with hypoestrogenism, anovulatory infertility, oligomenorrhoea, amenorrhoea, unexpected lactation and loss of libido in women and erectile dysfunction and loss of libido in men.[80]

Causes of Elevated Prolactin Levels

|

Physiological

|

Pharmacological

|

Pathological

|

|

Decreased levels

[edit]Hypoprolactinemia, or serum prolactin deficiency, is associated with ovarian dysfunction in women,[72][73] and arteriogenic erectile dysfunction, premature ejaculation,[74] oligozoospermia, asthenospermia, hypofunction of seminal vesicles and hypoandrogenism[75] in men. In one study, normal sperm characteristics were restored when prolactin levels were raised to normal values in hypoprolactinemic men.[76]

Hypoprolactinemia can result from hypopituitarism, excessive dopaminergic action in the tuberoinfundibular pathway and ingestion of D2 receptor agonists such as bromocriptine.[citation needed]

In medicine

[edit]Prolactin is available commercially for use in other animals, but not in humans.[81] It is used to stimulate lactation in animals.[81] The biological half-life of prolactin in humans is around 15–20 minutes.[82] The D2 receptor is involved in the regulation of prolactin secretion, and agonists of the receptor such as bromocriptine and cabergoline decrease prolactin levels while antagonists of the receptor such as domperidone, metoclopramide, haloperidol, risperidone, and sulpiride increase prolactin levels.[83] D2 receptor antagonists like domperidone, metoclopramide, and sulpiride are used as galactogogues to increase prolactin secretion in the pituitary gland and induce lactation in humans.[84]

See also

[edit]- Breast-feeding

- Breastfeeding and fertility

- Epileptic seizure

- Hyperprolactinaemia

- Hypothalamic–pituitary–prolactin axis

- Male lactation

- Prolactin modulator

- Prolactin receptor

- Prolactin-releasing hormone

- Prolactinoma

- Weaning

References

[edit]- ^ a b Beltran 2008 Table 2 Archived 9 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine reports measurements in mIU/L. AIA machines are calibrated to read the correct amount of μg/L against the second international standard IS 83/562, which has a potency of 27.0 mIU per μg.[79] By converting these measurements to mIU/L, Beltran makes measurements from machines calibrated against the second and third IS comparable, because the third IS is calibrated against the second to maintain the magnitude of the IU. However, the raw readout of the machine will still be in μg/L of IS-83/562-equivalent, unlike the other machines which report in μg/L of IS-84/500-equivalent.

- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000172179 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000021342 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ a b Bole-Feysot C, Goffin V, Edery M, Binart N, Kelly PA (June 1998). "Prolactin (PRL) and its receptor: actions, signal transduction pathways and phenotypes observed in PRL receptor knockout mice". Endocrine Reviews. 19 (3): 225–68. doi:10.1210/edrv.19.3.0334. PMID 9626554.

- ^ Ben-Jonathan N, Hugo ER, Brandebourg TD, LaPensee CR (April 2006). "Focus on prolactin as a metabolic hormone". Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism. 17 (3): 110–116. doi:10.1016/j.tem.2006.02.005. PMID 16517173. S2CID 37979194.

- ^ a b Ali M, Mirza L (1 May 2021). "Morbid Obesity Due to Prolactinoma and Significant Weight Loss After Dopamine Agonist Treatment". AACE Clinical Case Reports. 7 (3): 204–206. doi:10.1016/j.aace.2021.01.004. PMC 8165126. PMID 34095489.

- ^ Bates R, Riddle O (November 1935). "The preparation of prolactin". Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 55 (3): 365–371.

- ^ Friesen H, Guyda H, Hardy J (December 1970). "The biosynthesis of human growth hormone and prolactin". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 31 (6): 611–24. doi:10.1210/jcem-31-6-611. PMID 5483096. Archived from the original on 11 November 2013.

- ^ Evans AM, Petersen JW, Sekhon GS, DeMars R (May 1989). "Mapping of prolactin and tumor necrosis factor-beta genes on human chromosome 6p using lymphoblastoid cell deletion mutants". Somatic Cell and Molecular Genetics. 15 (3): 203–13. doi:10.1007/BF01534871. PMID 2567059. S2CID 36302971.

- ^ a b c Mizutani K, Takai Y (1 January 2018), "Prolactin", Reference Module in Biomedical Sciences, Elsevier, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-801238-3.98018-8, ISBN 978-0-12-801238-3, retrieved 10 January 2024

- ^ Lucas BK, Ormandy CJ, Binart N, Bridges RS, Kelly PA (October 1998). "Null mutation of the prolactin receptor gene produces a defect in maternal behavior". Endocrinology. 139 (10): 4102–7. doi:10.1210/endo.139.10.6243. PMID 9751488.

- ^ Ros M, Lobato MF, García-Ruíz JP, Moreno FJ (March 1990). "Integration of lipid metabolism in the mammary gland and adipose tissue by prolactin during lactation". Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry. 93 (2): 185–94. doi:10.1007/BF00226191. PMID 2345543. S2CID 19824793.

- ^ Ben-Jonathan N (1985). "Dopamine: a prolactin-inhibiting hormone". Endocrine Reviews. 6 (4): 564–89. doi:10.1210/edrv-6-4-564. PMID 2866952.

- ^ Freeman ME, Kanyicska B, Lerant A, Nagy G (October 2000). "Prolactin: structure, function, and regulation of secretion". Physiological Reviews. 80 (4): 1523–631. doi:10.1152/physrev.2000.80.4.1523. PMID 11015620.

- ^ Prolactinoma—Mayo Clinic

- ^ Hoehn K, Marieb EN (2007). Human Anatomy & Physiology. San Francisco: Pearson Benjamin Cummings. p. 605. ISBN 978-0-8053-5909-1.

- ^ Gonadotropins at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- ^ Grattan DR, Jasoni CL, Liu X, Anderson GM, Herbison AE (September 2007). "Prolactin regulation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons to suppress luteinizing hormone secretion in mice". Endocrinology. 148 (9): 4344–51. doi:10.1210/en.2007-0403. PMID 17569755.

- ^ Hair WM, Gubbay O, Jabbour HN, Lincoln GA (July 2002). "Prolactin receptor expression in human testis and accessory tissues: localization and function". Molecular Human Reproduction. 8 (7): 606–11. doi:10.1093/molehr/8.7.606. PMID 12087074.

- ^ Gregg C, Shikar V, Larsen P, Mak G, Chojnacki A, Yong VW, Weiss S (February 2007). "White matter plasticity and enhanced remyelination in the maternal CNS". The Journal of Neuroscience. 27 (8): 1812–23. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4441-06.2007. PMC 6673564. PMID 17314279.

- ^ Shingo T, Gregg C, Enwere E, Fujikawa H, Hassam R, Geary C, Cross JC, Weiss S (January 2003). "Pregnancy-stimulated neurogenesis in the adult female forebrain mediated by prolactin". Science. 299 (5603): 117–20. Bibcode:2003Sci...299..117S. doi:10.1126/science.1076647. PMID 12511652. S2CID 38577726.

- ^ Larsen CM, Grattan DR (February 2012). "Prolactin, neurogenesis, and maternal behaviors". Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 26 (2): 201–9. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2011.07.233. PMID 21820505. S2CID 27182670.

- ^ Huron D (13 July 2011). "Why is sad music pleasurable? A possible role for prolactin". Musicae Scientiae. 15 (2): 146–158. doi:10.1177/1029864911401171. S2CID 45981792.

- ^ Sakamoto T, McCormick SD (May 2006). "Prolactin and growth hormone in fish osmoregulation". General and Comparative Endocrinology. 147 (1): 24–30. doi:10.1016/j.ygcen.2005.10.008. PMID 16406056.

- ^ Whittington CM, Wilson AB (September 2013). "The role of prolactin in fish reproduction" (PDF). General and Comparative Endocrinology. 191: 123–36. doi:10.1016/j.ygcen.2013.05.027. PMID 23791758.

- ^ Khong HK, Kuah MK, Jaya-Ram A, Shu-Chien AC (May 2009). "Prolactin receptor mRNA is upregulated in discus fish (Symphysodon aequifasciata) skin during parental phase". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part B: Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 153 (1): 18–28. doi:10.1016/j.cbpb.2009.01.005. PMID 19272315.

- ^ Jiang RS, Xu GY, Zhang XQ, Yang N (June 2005). "Association of polymorphisms for prolactin and prolactin receptor genes with broody traits in chickens". Poultry Science. 84 (6): 839–845. doi:10.1093/ps/84.6.839. PMID 15971519.

- ^ Foitzik K, Krause K, Nixon AJ, Ford CA, Ohnemus U, Pearson AJ, Paus R (May 2003). "Prolactin and Its Receptor Are Expressed in Murine Hair Follicle Epithelium, Show Hair Cycle-Dependent Expression, and Induce Catagen". The American Journal of Pathology. 162 (5): 1611–21. doi:10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64295-2. PMC 1851183. PMID 12707045.

- ^ a b Craven AJ, Ormandy CJ, Robertson FG, Wilkins RJ, Kelly PA, Nixon AJ, Pearson AJ (June 2001). "Prolactin Signaling Influences the Timing Mechanism of the Hair Follicle: Analysis of Hair Growth Cycles in Prolactin Receptor Knockout Mice". Endocrinology. 142 (6): 2533–9. doi:10.1210/endo.142.6.8179. PMID 11356702.

- ^ Foitzik K, Krause K, Conrad F, Nakamura M, Funk W, Paus R (March 2006). "Human scalp hair follicles are both a target and a source of prolactin, which serves as an autocrine and/or paracrine promoter of apoptosis-driven hair follicle regression". The American Journal of Pathology. 168 (3): 748–56. doi:10.2353/ajpath.2006.050468. PMC 1606541. PMID 16507890.

- ^ a b Littlejohn MD, Henty KM, Tiplady K, Johnson T, Harland C, Lopdell T, Sherlock RG, Li W, Lukefahr SD, Shanks BC, Garrick DJ, Snell RG, Spelman RJ, Davis SR (December 2014). "Functionally reciprocal mutations of the prolactin signalling pathway define hairy and slick cattle". Nature Communications. 5: 5861. Bibcode:2014NatCo...5.5861L. doi:10.1038/ncomms6861. PMC 4284646. PMID 25519203.

- ^ Porto-Neto LR, Bickhart DM, Landaeta-Hernandez AJ, Utsunomiya YT, Pagan M, Jimenez E, Hansen PJ, Dikmen S, Schroeder SG, Kim ES, Sun J, Crespo E, Amati N, Cole JB, Null DJ, Garcia JF, Reverter A, Barendse W, Sonstegard TS (February 2018). "Convergent Evolution of Slick Coat in Cattle through Truncation Mutations in the Prolactin Receptor". Frontiers in Genetics. 9: 57. doi:10.3389/fgene.2018.00057. PMC 5829098. PMID 29527221.

- ^ Craven AJ, Nixon AJ, Ashby MG, Ormandy CJ, Blazek K, Wilkins RJ, Pearson AJ (November 2006). "Prolactin delays hair regrowth in mice". The Journal of Endocrinology. 191 (2): 415–25. doi:10.1677/joe.1.06685. hdl:10289/1353. PMID 17088411.

- ^ Dawson A (July 2006). "Control of molt in birds: association with prolactin and gonadal regression in starlings". General and Comparative Endocrinology. 147 (3): 314–22. doi:10.1016/j.ygcen.2006.02.001. PMID 16530194.

- ^ Derks MF, Herrero-Medrano JM, Crooijmans RP, Vereijken A, Long JA, Megens HJ, Groenen MA (February 2018). "Early and late feathering in turkey and chicken: same gene but different mutations". Genetics Selection Evolution. 50 (1): 7. doi:10.1186/s12711-018-0380-3. PMC 5863816. PMID 29566646.

- ^ Wang Y, Wang X, Luo Y, Zhang J, Lin Y, Wu J, Zeng B, Liu L, Yan P, Liang J, Guo H, Jin L, Tang Q, Long K, Li M (8 June 2023). "Spatio-temporal transcriptome dynamics coordinate rapid transition of core crop functions in 'lactating' pigeon". PLOS Genetics. 19 (6): e1010746. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1010746. ISSN 1553-7404. PMC 10249823. PMID 37289658.

- ^ a b Stewart C, Marshall CJ (2022). "Seasonality of prolactin in birds and mammals". Journal of Experimental Zoology Part A: Ecological and Integrative Physiology. 337 (9–10): 919–938. Bibcode:2022JEZA..337..919S. doi:10.1002/jez.2634. ISSN 2471-5638. PMC 9796654. PMID 35686456.

- ^ Ladyman SR, Hackwell EC, Brown RS (May 2020). "The role of prolactin in co-ordinating fertility and metabolic adaptations during reproduction". Neuropharmacology. 167: 107911. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2019.107911. PMID 32058177. S2CID 208985116.

- ^ Demirel MA, Suntar I, Ceribaşı S, Zengin G, Ceribaşı AO (1 August 2018). "Evaluation of the therapeutic effects of Artemisia absinthium L. on pseudopregnancy model in rats". Phytochemistry Reviews. 17 (4): 937–946. Bibcode:2018PChRv..17..937D. doi:10.1007/s11101-018-9571-3. ISSN 1572-980X. S2CID 4953983.

- ^ a b c Ormandy CJ, Binart N, Kelly PA (October 1997). "Mammary gland development in prolactin receptor knockout mice". J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2 (4): 355–64. doi:10.1023/a:1026395229025. PMID 10935023. S2CID 24217896.

- ^ Ben-Jonathan N, Mershon JL, Allen DL, Steinmetz RW (December 1996). "Extrapituitary prolactin: distribution, regulation, functions, and clinical aspects". Endocrine Reviews. 17 (6): 639–69. doi:10.1210/edrv-17-6-639. PMID 8969972.

- ^ a b c d Gerlo S, Davis JR, Mager DL, Kooijman R (October 2006). "Prolactin in man: a tale of two promoters". BioEssays. 28 (10): 1051–5. doi:10.1002/bies.20468. PMC 1891148. PMID 16998840.

- ^ Ben-Jonathan N. (2001) Hypothalamic control of prolactin synthesis and secretion . In: Horseman ND, ed. Prolactin. Boston: Kluwer; 1 –24

- ^ a b c d Ben-Jonathan N, LaPensee CR, LaPensee EW (February 2008). [18057139 "What can we learn from rodents about prolactin in humans?"]. Endocrine Reviews. 29 (1): 1–41. doi:10.1210/er.2007-0017. PMC 2244934. PMID 18057139.

{{cite journal}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Kulick RS, Chaiseha Y, Kang SW, Rozenboim I, El Halawani ME (July 2005). "The relative importance of vasoactive intestinal peptide and peptide histidine isoleucine as physiological regulators of prolactin in the domestic turkey". General and Comparative Endocrinology. 142 (3): 267–73. doi:10.1016/j.ygcen.2004.12.024. PMID 15935152.

- ^ Zinger M, McFarland M, Ben-Jonathan N (February 2003). "Prolactin expression and secretion by human breast glandular and adipose tissue explants". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 88 (2): 689–96. doi:10.1210/jc.2002-021255. PMID 12574200.

- ^ Calik-Ksepka A, Stradczuk M, Czarnecka K, Grymowicz M, Smolarczyk R (31 January 2022). "Lactational Amenorrhea: Neuroendocrine Pathways Controlling Fertility and Bone Turnover". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 23 (3): 1633. doi:10.3390/ijms23031633. ISSN 1422-0067. PMC 8835773. PMID 35163554.

- ^ Melmed S, Jameson JL (2005). "333 Disorders of the Anterior Pituitary and Hypothalamus". In Jameson JN, Kasper DL, Harrison TR, Braunwald E, Fauci AS, Hauser SL, Longo DL (eds.). Harrison's principles of internal medicine (16th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical Publishing Division. ISBN 978-0-07-140235-4.

- ^ Mellers JD (August 2005). "The approach to patients with "non-epileptic seizures"". Postgraduate Medical Journal. 81 (958): 498–504. doi:10.1136/pgmj.2004.029785. PMC 1743326. PMID 16085740.

- ^ "Prolactin". MedLine plus. Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- ^ a b Sobrinho LG (2003). "Prolactin, psychological stress and environment in humans: adaptation and maladaptation". Pituitary. 6 (1): 35–9. doi:10.1023/A:1026229810876. PMID 14674722. S2CID 1335211.

- ^ Welt CK, Barbieri RL, Geffner ME (2020). "Etiology, diagnosis, and treatment of secondary amenorrhea". UpToDate. Waltham, MA. Retrieved 7 November 2013.

- ^ Saleem M, Martin H, Coates P (February 2018). "Prolactin Biology and Laboratory Measurement: An Update on Physiology and Current Analytical Issues". The Clinical Biochemist. Reviews. 39 (1): 3–16. PMC 6069739. PMID 30072818.

- ^ a b c d Sabharwal P, Glaser R, Lafuse W, Varma S, Liu Q, Arkins S, Kooijman R, Kutz L, Kelley KW, Malarkey WB (August 1992). "Prolactin synthesized and secreted by human peripheral blood mononuclear cells: an autocrine growth factor for lymphoproliferation". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 89 (16): 7713–6. Bibcode:1992PNAS...89.7713S. doi:10.1073/pnas.89.16.7713. PMC 49781. PMID 1502189., in turn citing: Kiefer KA, Malarkey WB (January 1978). "Size heterogeneity of human prolactin in CSF and serum: experimental conditions that alter gel filtration patterns". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 46 (1): 119–24. doi:10.1210/jcem-46-1-119. PMID 752015.

- ^ Garnier PE, Aubert ML, Kaplan SL, Grumbach MM (December 1978). "Heterogeneity of pituitary and plasma prolactin in man: decreased affinity of "Big" prolactin in a radioreceptor assay and evidence for its secretion". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 47 (6): 1273–81. doi:10.1210/jcem-47-6-1273. PMID 263349.

- ^ Leite V, Cosby H, Sobrinho LG, Fresnoza MA, Santos MA, Friesen HG (October 1992). "Characterization of big, big prolactin in patients with hyperprolactinaemia". Clinical Endocrinology. 37 (4): 365–72. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.1992.tb02340.x. PMID 1483294. S2CID 42796831.

- ^ Kamel MA, Neulen J, Sayed GH, Salem HT, Breckwoldt M (September 1993). "Heterogeneity of human prolactin levels in serum during the early postpartum period". Gynecological Endocrinology. 7 (3): 173–7. doi:10.3109/09513599309152499. PMID 8291454.

- ^ a b c d e Mancini T, Casanueva FF, Giustina A (March 2008). "Hyperprolactinemia and prolactinomas". Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America. 37 (1): 67–99, viii. doi:10.1016/j.ecl.2007.10.013. PMID 18226731.

- ^ Utama FE, LeBaron MJ, Neilson LM, Sultan AS, Parlow AF, Wagner KU, Rui H (March 2006). "Human prolactin receptors are insensitive to mouse prolactin: implications for xenotransplant modeling of human breast cancer in mice". The Journal of Endocrinology. 188 (3): 589–601. doi:10.1677/joe.1.06560. PMID 16522738.

- ^ Al-Chalabi M, Bass AN, Alsalman I (2023), "Physiology, Prolactin", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 29939606, retrieved 10 January 2024

- ^ Banerjee S, Paul P, Talib VJ (August 2004). "Serum prolactin in seizure disorders". Indian Pediatrics. 41 (8): 827–31. PMID 15347871.

- ^ a b c d Schulster D, Gaines Das RE, Jeffcoate SL (April 1989). "International Standards for human prolactin: calibration by international collaborative study". The Journal of Endocrinology. 121 (1): 157–66. doi:10.1677/joe.0.1210157. PMID 2715755.

- ^ a b c "WHO Expert Committee on Biological Standardization" (PDF). Thirty-ninth Report, WHO Technical Report Series. World Health Organization. 1989. Retrieved 3 June 2009.

86.1520, WHO/BS documents: 86.1520 Add 1, 88.1596

- ^ "WHO International Standard, Prolactin, Human. NIBSC code: 84/500, Instructions for use" (PDF). NIBSC / Health Protection Agency. 1989. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 October 2011. Retrieved 21 March 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f Canadian Society of Clinical Chemists (December 1992). "Canadian Society of Clinical Chemists position paper: standardization of selected polypeptide hormone measurements". Clinical Biochemistry. 25 (6): 415–24. doi:10.1016/0009-9120(92)90030-V. PMID 1477965.

- ^ a b Gaines Das RE, Cotes PM (January 1979). "International Reference Preparation of human prolactin for immunoassay: definition of the International Unit, report of a collaborative study and comparison of estimates of human prolactin made in various laboratories". The Journal of Endocrinology. 80 (1): 157–68. doi:10.1677/joe.0.0800157. PMID 429949.

- ^ a b "WHO Expert Committee on Biological Standardization" (PDF). Thirty-fifth Report, WHO Technical Report Series. World Health Organization. 1985. Retrieved 21 March 2011.

- ^ a b c "WHO Expert Committee on Biological Standardization" (PDF). Thirty-seventh Report, WHO Technical Report Series. World Health Organization. 1987. Retrieved 21 March 2011.[dead link]

- ^ a b Bangham DR, Mussett MV, Stack-Dunne MP (1963). "The Second International Standard for Prolactin". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 29 (6): 721–8. PMC 2555104. PMID 14107744.

- ^ Ferguson J (2016). "WHO International Collaborative Study of the Proposed 4th International Standard for Prolactin, Human".

- ^ a b Kauppila A, Martikainen H, Puistola U, Reinilä M, Rönnberg L (March 1988). "Hypoprolactinemia and ovarian function". Fertility and Sterility. 49 (3): 437–41. doi:10.1016/s0015-0282(16)59769-6. PMID 3342895.

- ^ a b Schwärzler P, Untergasser G, Hermann M, Dirnhofer S, Abendstein B, Berger P (October 1997). "Prolactin gene expression and prolactin protein in premenopausal and postmenopausal human ovaries". Fertility and Sterility. 68 (4): 696–701. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(97)00320-8. PMID 9341613.

- ^ a b Corona G, Mannucci E, Jannini EA, Lotti F, Ricca V, Monami M, Boddi V, Bandini E, Balercia G, Forti G, Maggi M (May 2009). "Hypoprolactinemia: a new clinical syndrome in patients with sexual dysfunction". The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 6 (5): 1457–66. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.01206.x. PMID 19210705.

- ^ a b Gonzales GF, Velasquez G, Garcia-Hjarles M (1989). "Hypoprolactinemia as related to seminal quality and serum testosterone". Archives of Andrology. 23 (3): 259–65. doi:10.3109/01485018908986849. PMID 2619414.

- ^ a b Ufearo CS, Orisakwe OE (September 1995). "Restoration of normal sperm characteristics in hypoprolactinemic infertile men treated with metoclopramide and exogenous human prolactin". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 58 (3): 354–9. doi:10.1016/0009-9236(95)90253-8. PMID 7554710. S2CID 1735908.

- ^ a b Table 2 Archived 9 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine in Beltran L, Fahie-Wilson MN, McKenna TJ, Kavanagh L, Smith TP (October 2008). "Serum total prolactin and monomeric prolactin reference intervals determined by precipitation with polyethylene glycol: evaluation and validation on common immunoassay platforms". Clinical Chemistry. 54 (10): 1673–81. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2008.105312. PMID 18719199.

- ^ a b c d e Prolaktin Archived 28 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine at medical.siemens.com—reference ranges as determined from the IMMULITE assay method

- ^ "CL AIA-PACK® Prolactin TEST CUP" (PDF).

- ^ Melmed S, Kleinberg D 2008 Anterior pituitary. 1n: Kronenberg HM, Melmed S, Polonsky KS, Larsen PR, eds. Willams textbook of endocrinology. 11th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 185–261

- ^ a b Coutts RT, Smail GA (12 May 2014). Polysaccharides Peptides and Proteins: Pharmaceutical Monographs. Elsevier. pp. 153–. ISBN 978-1-4831-9612-1.

- ^ D.F. Horrobin (6 December 2012). Prolactin: Physiology and Clinical Significance. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 13–. ISBN 978-94-010-9695-9.

- ^ Martin H. Johnson (14 December 2012). Essential Reproduction. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 40–. ISBN 978-1-118-42388-2.

- ^ Jan Riordan (January 2005). Breastfeeding and Human Lactation. Jones & Bartlett Learning. pp. 468–. ISBN 978-0-7637-4585-1.