Pulmonary circulation

| Pulmonary circulation | |

|---|---|

Pulmonary circulation in the heart | |

| Details | |

| System | Circulatory system |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D011652 |

| TA2 | 4073 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The pulmonary circulation is a division of the circulatory system in all vertebrates. The circuit begins with deoxygenated blood returned from the body to the right atrium of the heart where it is pumped out from the right ventricle to the lungs. In the lungs the blood is oxygenated and returned to the left atrium to complete the circuit.[1]

The other division of the circulatory system is the systemic circulation that begins upon the oxygenated blood reaching the left atrium from the pulmonary circulation. From the atrium the oxygenated blood enters the left ventricle where it is pumped out to the rest of the body, then returning as deoxygenated blood back to the pulmonary circulation.

A separate circulatory circuit known as the bronchial circulation supplies oxygenated blood to the tissues of the lung that do not directly participate in gas exchange.

Anatomy

[edit]

The pulmonary arteries have both an internal and external elastic membrane, whereas pulmonary veins have a single (outer) elastic layer.[2]

Arteries

[edit]From the right ventricle, blood is pumped through the semilunar pulmonary valve into the left and right main pulmonary artery (one for each lung), which branch into smaller pulmonary arteries that spread throughout the lungs.[3][4]

Veins

[edit]Oxygenated blood leaves the lungs through pulmonary veins, which return it to the left part of the heart, completing the pulmonary cycle.[3][4]

Physiology

[edit]Two pulmonary circulations

[edit]The lung actually possesses a high-flow, low-pressure circulation which passes deoxygenated blood from the right heart through the capillaries surrounding the alveoli to be oxygenated, and a low-flow, high-pressure (just slightly lower than systemic arterial pressure) circulation which supplies oxygenated blood to other structures of the lung (airways, supporting tissues, and the vasa vasorum) via the bronchial arteries. This oxygenated blood supplied by the bronchial arteries amounts to 1-2% of left heart output, and is drained into the pulmonary venous system and returned to the left atrium.[5]

Pulmonary arterial pressure normally measures about 25 mmHg during systole, about 8 mmHg during diastole, for a mean arterial pressure of 15 mmHg.[5]

Capacity and compliance

[edit]The pulmonary arteries and veins are short vessels. To accommodate the right ventricular stroke volume, the pulmonary arterial system has very high compliance; this is achieved by all pulmonary arteries possessing much larger diameters compared to systemic counterparts, as well as thin and distensible walls. Pulmonary blood flow is essentially equal to cardiac output. Pulmonary vessels typically function as distensible conduits that distend at higher intraluminal pressures and narrow with lower pressures.[5]

Blood flow, blood pressure and vascular resistance

[edit]The (alveolar) pulmonary circulation operates as a very low pressure and resistance system. Indeed, blood pressure in the circulation is normally just sufficient to maintain blood flow in all parts of the lungs. Nevertheless, the pulmonary circulation can accommodate significantly increased flow during periods of increased demand. Abnormally high blood pressures in the pulmonary circulation (e.g. in left-sided heart failure) cause excess fluid to transude from the blood vessels into the alveoli and accumulate here, causing pulmonary edema and impairing gas exchange.[6] Pulmonary capillary pressure is estimated to normally stand at about 7mmHg (compared to about 17 mmHg in capillaries of the systemic circulation), though it has not been measured directly.[5]

During very heavy demand (e.g. during strenuous exercise), pulmonary blood flow may be increased to 4-fold to 7-fold of normal. The additional blood flow is accomodated by increasing the number of open capillaries (up to 3-fold greater), distending capillaries (up to 2-fold greater flow), and increasing pulmonary blood pressure; the former two mechanisms accommodate the additional blood flow by reducing vascular resistance and can normally accommodate all the additional required blood flow even at peak demand with little additional increase of pulmonary blood pressure.[5]

Blood normally passes through a pulmonary capillary in about 0.8 s, but the time spent traversing the capillaries is as little as 0.3 s during maximal blood flow.[5]

Autoregulation of alveolar blood flow

[edit]Lung tissue is capable of reducing perfusion of poorly ventilated alveoli to redirect blood flow to better ventilated ones. Reduced O2 concentration in an alveolus causes adjacent blood vessels to constrict; vascular resistance may increase more than 5-fold with very low alveolar O2 levels. Hypoxic vasoconstriction of alveolar blood vessels is thought to be mediated by increased action of vasoconstrictors (e.g. endothelin, and reactive oxygen species), decreased release of vasodilators (e.g. nitric oxide), and closing of oxygen-sensitive K+ channels in vascular smooth muscle (directly causing depolarisation and consequent constriction of muscle).[5]

Hydrostatic effects and pulmonary blood flow

[edit]The hydrostatic pressure of blood within blood vessels exhibits a gradient across the lung (as do blood vessels across any axis of the body). In an upright person, the lung normally measures 30 cm top-to-bottom for a hydrostatic pressure gradient of 23 mmHg, of which 15 mmHg is superior to the level of the heart. Consequently, in a standing person at rest, there is 5 times more blood flow at the bottom of the lung than at the top.[5]

The hydrostatic pressure gradient can lead to three different blood flow scenarios in different parts of the lung:[5]

- Zone 1: upper-most zone where alveolar pressure always exceeds capillary blood pressure and no blood flow occurs.

- Zone 2: intermediate zone where peak capillary blood pressure exceeds alveolar pressure during systole, but alveolar pressure always exceeds diastolic blood pressure, so that some blood flows through the capillaries but only during systole.

- Zone 3: lower zone where capillary blood pressure during diastole exceeds alveolar pressure so that blood flow is continuous.

Normally, only zone 2 and zone 3 blood flow occurs in the lungs: as normal systolic pulmonary blood pressure is ~25 mmHg at heart level and the hydrostatic pressure of the blood is 15 mmHg at the top of the lung, capillary pressure at the top of the lung will amount to ~10 mmHg during systole, but because normal diastolic pulmonary blood pressure is only 8 mmHg, no blood flow will occur in parts of the lung where hydrostatic pressure of the blood exceeds 7 mmHg (this limit is situated about 10 cm about the level of the heart in vivo).[5]

Zone 1 blood flow occurs in the context of either abnormally low systolic pulmonary blood pressure, or abnormally high alveolar pressure. When alveolar pressure exceeds capillary blood pressure, capillaries collapse and blood flow ceases. Increased blood flow through the pulmonary circulation (e.g. during physical exertion) causes zone 2 parts of the lung to progressively transition to zone 3 patterns of blood flow.[5]

Pulmonary blood volume

[edit]Pulmonary blood volume is normally about 450 mL (about 9% of total blood volume); about 70mL of this amount is contained within pulmonary capillaries, and the remainder is roughly equally distributed between the pulmonary arterial and venous systems.[5]

The pulmonary blood pool may range from half of the normal amount to twice the normal amount as result of various physiological or pathological conditions. Vigorous expiration that creates high pressures within the lungs can cause as much as 250 mL of blood to be ejected from the pulmonary circulation. The pulmonary blood pool can act as a blood reserve that can be mobilised into the systemic circulation (e.g. after blood loss). Dysfunction of the left heart can cause significant amounts of blood to dam up in the pulmonary circulation.[5]

Development

[edit]The pulmonary circulation loop is virtually bypassed in fetal circulation.[7] The fetal lungs are collapsed, and blood passes from the right atrium directly into the left atrium through the foramen ovale (an open conduit between the paired atria) or through the ductus arteriosus (a shunt between the pulmonary artery and the aorta).[7]

When the lungs expand at birth, the pulmonary pressure drops and blood is drawn from the right atrium into the right ventricle and through the pulmonary circuit. Over the course of several months, the foramen ovale closes, leaving a shallow depression known as the fossa ovalis.[7][8]

Clinical significance

[edit]A number of medical conditions may affect the pulmonary circulation:

- Pulmonary hypertension describes an increase in resistance in the pulmonary arteries.[9]

- Pulmonary embolism is occlusion or partial occlusion of the pulmonary artery or its branches by an embolus, usually from the embolization of a blood clot from deep vein thrombosis.[10] It can cause difficulty breathing or chest pain, is usually diagnosed through a CT pulmonary angiography or V/Q scan, and is often treated with anticoagulants such as heparin and warfarin.[11]

- Cardiac shunt is an unnatural connection between parts of the heart that leads to blood flow that bypasses the lungs.[12]

- Vascular resistance[13]

- Pulmonary shunt[citation needed]

History

[edit]

The pulmonary circulation is archaically known as the "lesser circulation" which is still used in non-English literature.[14][15]

The discovery of the pulmonary circulation has been attributed to many scientists with credit distributed in varying ratios by varying sources. In much of modern medical literature, the discovery is credited to English physician William Harvey (1578 – 1657 CE) based on the comprehensive completeness and correctness of his model, despite its relative recency.[16][17] Other sources credit one or more of Greek philosopher Hippocrates (460 – 370 BCE), Arab physician Ibn al-Nafis (1213 – 1288 CE), Syrian physician Qusta ibn Luqa or Spanish physician Michael Servetus (c. 1509 – 1553 CE).[18][19][20][21] Several figures such as Hippocrates and al-Nafis receive credit for accurately predicting or developing specific elements of the modern model of pulmonary circulation: Hippocrates[20] for being the first to describe pulmonary circulation as a discrete system separable from systemic circulation as a whole and al-Nafis[22] for making great strides over the understanding of those before him and towards a rigorous model. There is a great deal of subjectivity involved in deciding at which point a complex system is "discovered", as it is typically elucidated in piecemeal form so that the very first description, most complete or accurate description, and the most significant forward leaps in understanding are all considered acts of discovery of varying significance.[20]

Early descriptions of the cardiovascular system are found throughout several ancient cultures. The earliest known description of the role of air in circulation was produced in Egypt in 3500 BCE. At the time, the Egyptians believed that the heart was the origin of many channels that connected different parts of the body to each other and transported air – as well as urine, blood, and the soul – between them.[23] The Edwin Smith Papyrus (1700 BCE), named for American Egyptologist Edwin Smith (1822 – 1906 CE) who purchased the scroll in 1862, provided evidence that Egyptians believed that the heartbeat created a pulse that transported the above substances throughout the body.[24] A second scroll, the Ebers Papyrus (c. 1550 BCE), also emphasized the importance of the heart and its connection to vessels throughout the body and described methods to detect cardiac disease through pulse abnormalities. Although they had knowledge of the heartbeat, vessels, and pulse, the Egyptians attributed the movement of substances through the vessels to air that resided in these channels, rather than to the heart's exertion of pressure.[25]The Egyptians knew that air played an important role in circulation but did not yet have a conception of the role of the lungs.

The next addition to the historical understanding of pulmonary circulation arrived with the Ancient Greeks. Physician Alcmaeon (520 – 450 BCE) proposed that the brain, not the heart, was the connection point for all of the vessels in the body. He believed that the function of these vessels was to bring the "spirit" ("pneuma") and air to the brain.[23][26] Empedocles (492 – 432 BCE), a philosopher, proposed a series of pipes, impermeable to blood but continuous with blood vessels, that carried the pneuma throughout the body. He proposed that this spirit was internalized by pulmonary respiration.[23]

Hippocrates was the first to describe pulmonary circulation as a discrete system, separable from systemic circulation, in his Corpus Hippocraticum, which is often regarded as the foundational text of modern medicine.[20] Hippocrates developed the view that the liver and spleen produced blood, and that this traveled to the heart to be cooled by the lungs that surrounded it.[19] He described the heart as having two ventricles connected by an interventricular septum, and depicted the heart as the nexus point of all of the vessels of the body. He proposed that some vessels carried only blood and that others carried only air. He hypothesized that these air-carrying vessels were divisible into the pulmonary veins, which carried in air to the left ventricle, and the pulmonary artery, which carried in air to the right ventricle and blood to the lungs. He also proposed the existence of two atria of the heart functioning to capture air. He was one of the first to begin to accurately describe the anatomy of the heart and to describe the involvement of the lungs in circulation. His descriptions built substantially on previous and contemporaneous efforts but, by modern standards, his conceptions of pulmonary circulation and of the functions of the parts of the heart were still largely inaccurate.[23]

Greek philosopher and scientist Aristotle (384 – 322 BCE) followed Hippocrates and proposed that the heart had three ventricles, rather than two, that all connected to the lungs.[23] Greek physician Erasistratus (315 – 240 BCE) agreed with Hippocrates and Aristotle that the heart was the origin of all of the vessels in the body but proposed a system in which air was drawn into the lungs and traveled to the left ventricle via pulmonary veins. It was transformed there into the pneuma and distributed throughout the body by arteries, which contained only air.[24] In this system, veins distributed blood throughout the body, and thus blood did not circulate, but rather was consumed by the organs.[23]

The Greek physician Galen (129 – c. 210 CE) provided the next insights into pulmonary circulation. Though many of his theories, like those of his predecessors, were marginally or completely incorrect, his theory of pulmonary circulation dominated the medical community's understanding for hundreds of years after his death.[24] Galen contradicted Erasistratus before him by proposing that arteries carried both air and blood, rather than air alone (which was essentially correct, leaving aside that blood vessels carry constituents of air and not air itself).[19] He proposed that the liver was the originating point of all blood vessels. He also theorized that the heart was not a pumping muscle but rather an organ through which blood passed.[24] Galen's theory included a new description of pulmonary circulation: air was inhaled into the lungs where it became the pneuma. Pulmonary veins transmitted this pneuma to the left ventricle of the heart to cool the blood simultaneously arriving there. This mixture of pneuma, blood, and cooling produced the vital spirits that could then be transported throughout the body via arteries. Galen further proposed that the heat of the blood arriving in the heart produced noxious vapors that were expelled through the same pulmonary veins that first brought the pneuma.[27] He wrote that the right ventricle played a different role to the left: it transported blood to the lungs where the impurities were vented out so that clean blood could be distributed throughout the body. Though Galen's description of the anatomy of the heart was more complete than those of his predecessors, it included several mistakes. Most notably, Galen believed that blood flowed between the two ventricles of the heart through small, invisible pores in the interventricular septum.[23]

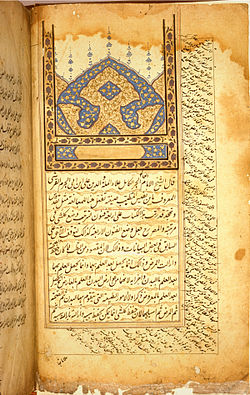

The next significant developments in the understanding of pulmonary circulation did not arrive until centuries later. Persian polymath Avicenna (c. 980 – 1037 CE) wrote a medical encyclopedia entitled The Canon of Medicine. In it, he translated and compiled contemporary medical knowledge and added some new information of his own.[22] However, Avicenna's description of pulmonary circulation reflected the incorrect views of Galen.[19]

The Arab physician, Ibn al-Nafis, wrote the Commentary on Anatomy in Avicenna's Canon in 1242 in which he provided possibly the first known description of the system that remains substantially congruent with modern understandings, in spite of its flaws. Ibn al-Nafis made two key improvements on Galen's ideas. First, he disproved the existence of the pores in the interventricular septum that Galen had believed allowed blood to flow between the left and right ventricles. Second, he surmised that the only way for blood to get from the right to the left ventricle in the absence of interventricular pores was a system like pulmonary circulation. He also described the anatomy of the lungs in clear and basically correct detail, which his predecessors had not.[22] However, like Aristotle and Galen, al-Nafis still believed in the quasi-mythical concept of vital spirit and that it was formed in the left ventricle from a mixture of blood and air. Despite the enormity of Ibn al-Nafis's improvements on the theories that preceded him, his commentary on The Canon was not widely known to Western scholars until the manuscript was discovered in Berlin, Germany, in 1924. As a result, the ongoing debate among Western scholars as to how credit for the discovery should be apportioned failed to include Ibn al-Nafis until, at earliest, the mid-20th century (shortly after which he came to enjoy a share of this credit).[19][22] In 2021, several researchers described a text predating the work of al-Nafis, fargh- beyn-roh va nafs, in which there is a comparable report on pulmonary circulation. The researchers argue that its author, Qusta ibn Luqa, is the best candidate for the discoverer of pulmonary circulation on a similar basis to arguments in favour of al-Nafis generally.[21]

It took centuries for other scientists and physicians to reach conclusions that were similar to and then more accurate than those of al-Nafis and ibn Luqa. This later progress, constituting the gap between medieval and modern understanding, occurred throughout Europe. Italian polymath Leonardo da Vinci (1452 – 1519 CE) was one of the first to propose that the heart was just a muscle, rather than a vessel of spirits and air, but he still subscribed to Galen's ideas of circulation and defended the existence of interventricular pores.[23] The Flemish physician Andreas Vesalius (1514 – 1564 CE) published corrections to Galen's view of circulatory anatomy, questioning the existence of interventricular pores, in his book De humani corporis fabrica libri septem in 1543.[27] Spanish Michael Servetus, after him, was the first European physician to accurately describe pulmonary circulation.[18] His assertions largely matched those of al-Nafis. In subsequent centuries, he has frequently been credited with the discovery, but some historians have propounded the idea that he potentially had access to Ibn al-Nafis's work while writing his own texts.[19] Servetus published his findings in Christianismi Restituto (1553): a theological work that was considered heretical by Catholics and Calvinists alike. As a result, both book and author were burned at the stake and only a few copies of his work survived.[19] Italian physician Realdo Colombo (c. 1515 – 1559 CE) published a book, De re anatomica libri XV, in 1559 that accurately described pulmonary circulation. It is still a matter of debate among historians as to whether Colombo reached his conclusions alone or based them to an unknown degree on the works of al-Nafis and Servetus.[19][23] Finally, in 1628, the influential British physician William Harvey (1578 – 1657 AD) provided at the time the most complete and accurate description of pulmonary circulation of any scholar worldwide in his treatise Exercitatio Anatomica de Motu Cordis et Sanguinis in Animalibus. At the macroscopic level, his model is still recognizable in and reconcilable with modern understandings of pulmonary circulation.[16]

References

[edit]- ^ Hine R (2008). A dictionary of biology (6th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 540. ISBN 978-0-19-920462-5.

- ^ Goldblum, John R.; Lamps, Laura Webb; McKenney, Jesse K.; Myers, Jeffrey L.; Ackerman, Lauren Vedder, eds. (2018). Rosai and Ackerman's surgical pathology (11th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-323-26339-9.

- ^ a b Ehrlich, Ann; Schroeder, Carol L.; Ehrlich, Laura; Schroeder, Katrina A (2016). Medical Terminology for Health Professions, Spiral bound Version. Cengage Learning. p. 128. ISBN 978-1-305-88714-5.

- ^ a b Cohen, Barbara Janson; Jones, Shirley A (2020). Medical Terminology: An Illustrated Guide. Jones & Bartlett Learning. pp. 317–318. ISBN 978-1-284-21880-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Hall, John E.; Hall, Michael E. (2021). "Chapter 39 - Pulmonary Circulation, Pulmonary Edema, and Pleural Fluid". Guyton and Hall Textbook of Medical Physiology (14th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-323-59712-8.

- ^ Arroyo, Juan Pablo; Schweickert, Adam J. (2015). Back to Basics in Physiology: O2 and CO2 in the Respiratory and Cardiovascular Systems. Elsevier/Academic Press. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-12-801768-5. OCLC 903596350.

- ^ a b c McConnell, Thomas H; Hull, Kerry L. (2020). Human Form, Human Function: Essentials of Anatomy & Physiology, Enhanced Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 703. ISBN 978-1-284-21805-3.

- ^ Davis, FA (2016). Taber's Quick Reference for Cardiology and Pulmonology. F.A. Davis. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-8036-4721-3.

- ^ Anderson, Robert H.; Krishna, Kumar; Mussato, Kathleen A.; Redington, Andrew; Tweddell, James S.; Tretter, Justin (2020). Anderson's Pediatric Cardiology E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. PA1381. ISBN 978-0-7020-7924-5.

- ^ L. McCance, Kathryn; Huether, Sue E. (2018). Pathophysiology - E-Book: The Biologic Basis for Disease in Adults and Children. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 1190. ISBN 978-0-323-41320-6.

- ^ Moini, Jahangir; Piran, Pirouz (2020). Functional and Clinical Neuroanatomy: A Guide for Health Care Professionals. Academic Press. pp. 146–147. ISBN 978-0-12-817425-8.

- ^ Joffe, Denise C.; Shi, Mark R.; Welker, Carson C. (April 2018). "Understanding cardiac shunts". Pediatric Anesthesia. 28 (4): 316–325. doi:10.1111/pan.13347. PMID 29508477. S2CID 4323077.

- ^ Widrich, J; Shetty, M (March 2021). "Physiology, Pulmonary Vascular Resistance". StatPearls Publishing. PMID 32119267.

- ^ "lesser circulation". TheFreeDictionary.com. Retrieved 2021-07-09.

- ^ de Man, Frances S.; La Gerche, Andre (2017-10-01). "A focus on the greatness of the lesser circulation: spotlight issue on the right ventricle". Cardiovascular Research. 113 (12): 1421–1422. doi:10.1093/cvr/cvx168. ISSN 0008-6363. PMID 28957539.

- ^ a b Ribatti D (September 2009). "William Harvey and the discovery of the circulation of the blood". Journal of Angiogenesis Research. 1: 3. doi:10.1186/2040-2384-1-3. PMC 2776239. PMID 19946411.

- ^ Azizi MH, Nayernouri T, Azizi F (May 2008). "A brief history of the discovery of the circulation of blood in the human body" (PDF). Archives of Iranian Medicine. 11 (3): 345–50. PMID 18426332.

- ^ a b Bosmia A, Watanabe K, Shoja MM, Loukas M, Tubbs RS (July 2013). "Michael Servetus (1511-1553): physician and heretic who described the pulmonary circulation". International Journal of Cardiology. 167 (2): 318–21. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.06.046. PMID 22748500.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Akmal M, Zulkifle M, Ansari A (March 2010). "Ibn nafis - a forgotten genius in the discovery of pulmonary blood circulation". Heart Views. 11 (1): 26–30. PMC 2964710. PMID 21042463.

- ^ a b c d Gregory Tsoucalas; Markos Sgantzos (21 March 2017). "The pulmonary circulation, it all started in the Hippocratic era". European Heart Journal. 38 (12): 851. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehx072. PMID 28931233.

- ^ a b Mahlooji, Kamran; Abdoli, Mahsima; Tekiner, Halil; Zargaran, Arman (2021-03-23). "A new evidence on pulmonary circulation discovery: A text of Ibn Luqa (860 - 912 CE)". European Heart Journal. 42 (26): 2522–2523. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehab039. ISSN 1522-9645. PMID 33755117.

- ^ a b c d West JB (December 2008). "Ibn al-Nafis, the pulmonary circulation, and the Islamic Golden Age". Journal of Applied Physiology. 105 (6): 1877–80. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.91171.2008. PMC 2612469. PMID 18845773.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Bestetti RB, Restini CB, Couto LB (December 2014). "Development of anatomophysiologic knowledge regarding the cardiovascular system: from Egyptians to Harvey". Arquivos Brasileiros de Cardiologia. 103 (6): 538–45. doi:10.5935/abc.20140148. PMC 4290745. PMID 25590934.

- ^ a b c d ElMaghawry M, Zanatta A, Zampieri F (2014). "The discovery of pulmonary circulation: From Imhotep to William Harvey". Global Cardiology Science & Practice. 2014 (2): 103–16. doi:10.5339/gcsp.2014.31. PMC 4220440. PMID 25405183.

- ^ Nunn, J. F. (1996). Ancient Egyptian Medicine. Vol. 113. London: British Museum Press. pp. 57–68. ISBN 978-0-7141-0981-7. PMID 10326089.

- ^ Loukas M, Tubbs RS, Louis RG, Pinyard J, Vaid S, Curry B (August 2007). "The cardiovascular system in the pre-Hippocratic era". International Journal of Cardiology. 120 (2): 145–9. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.11.122. PMID 17316844.

- ^ a b Aird WC (July 2011). "Discovery of the cardiovascular system: from Galen to William Harvey". Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 9 (Suppl. 1): 118–29. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04312.x. PMID 21781247. S2CID 12092592.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Pulmonary circulation at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Pulmonary circulation at Wikimedia Commons