Skutterudite

| Skutterudite | |

|---|---|

Skutterudite from Bou Azzer, Morocco | |

| General | |

| Category | Arsenide mineral |

| Formula | CoAs3 |

| IMA symbol | Skt[1] |

| Strunz classification | 2.EC.05 |

| Crystal system | Cubic |

| Crystal class | Diploidal (m3) H-M symbol: (2/m 3) |

| Space group | Im3 |

| Unit cell | a = 8.204 Å, Z = 8 |

| Identification | |

| Color | Tin-white to silver-gray, tarnishes gray or iridescent; in polished section, gray, creamy or golden white |

| Crystal habit | Crystals are cubes, octahedra, dodecahedra, rarely prismatic; in skeletal growth forms, distorted aggregates; also massive, granular |

| Twinning | On {112} as sixlings and complex shapes |

| Cleavage | Distinct on {001} and {111}; in traces on {011} |

| Fracture | Conchoidal to uneven |

| Mohs scale hardness | 5.5–6 |

| Luster | Metallic |

| Streak | Black |

| Diaphaneity | Opaque |

| Specific gravity | 6.5 |

| References | [2][3][4][5] |

Skutterudite is a cobalt arsenide mineral containing variable amounts of nickel and iron substituting for cobalt with the ideal formula CoAs3. Some references give the arsenic a variable formula subscript of 2–3. High nickel varieties are referred to as nickel-skutterudite, previously chloanthite. It is a hydrothermal ore mineral found in moderate to high temperature veins with other Ni-Co minerals. Associated minerals are arsenopyrite, native silver, erythrite, annabergite, nickeline, cobaltite, silver sulfosalts, native bismuth, calcite, siderite, barite and quartz.[3] It is mined as an ore of cobalt and nickel with a by-product of arsenic.

The crystal structure of this mineral has been found to be exhibited by several compounds with important technological uses.

The mineral has a bright metallic luster, and is tin white or light steel gray in color with a black streak. The specific gravity is 6.5 and the hardness is 5.5–6. Its crystal structure is isometric with cube and octahedron forms similar to that of pyrite. The arsenic content gives a garlic odor when heated or crushed.

Origins

[edit]Skutterudite has been known since the Middle Ages, when it was used in the production of smalt.[6][7] It was discovered in the Skuterud Mines, Modum, Buskerud, Norway, in 1845.[4] Smaltite is an alternative name for the mineral.[8] Notable occurrences include Cobalt, Ontario[9] and Franklin, New Jersey, in the United States.[10]

Structure

[edit]

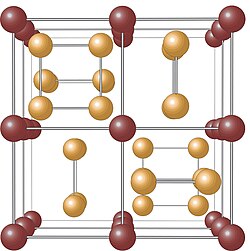

The crystal structure of the skutterudite mineral was determined in 1928 by Oftedahl to be cubic, belonging to space group Im 3 (number 204).[11][12]

The unit cell of a skutterudite consists of a total of 32 atoms,[13] arranged in eight smaller cubes composed of cobalt atoms, which form octahedra with cobalt at the center. Six of these cubes are filled with planar square rings of arsenic, each oriented parallel to one of the unit cell's edges.[14] In its structure, at the 2a Wyckoff position, there are two large structural voids—each approximately five angstroms in size—that can be filled with impurity atoms.[15][16] Together with the unit cell size and the assigned space group, the parameters mentioned above fully describe the crystalline structure of the material. This structure is commonly referred to as a skutterudite structure.[17]

Applications

[edit]Materials with a skutterudite structure are studied as a low cost thermoelectric material[18] with low thermal conductivity.[19][20] These materials have been synthesized with a thermoelectric figure of merit (ZT) close to 1 at 800 kelvin.[21] A relatively high dimensionless figure of merit has been observed in a polycrystalline skutterudite partially filled with ytterbium ions. The small-diameter but heavy ytterbium atoms partially occupy the voids in the CoSb3 host structure, resulting in low thermal conductivity values while the favorable electronic properties are not substantially disrupted by the addition of ytterbium.[22]

References

[edit]- ^ Warr, L.N. (2021). "IMA–CNMNC approved mineral symbols". Mineralogical Magazine. 85 (3): 291–320. Bibcode:2021MinM...85..291W. doi:10.1180/mgm.2021.43. S2CID 235729616.

- ^ "Skutterudite". Mineral Atlas. 2025. Retrieved May 29, 2025.

- ^ a b Anthony, John W.; Bideaux, Richard A.; Bladh, Kenneth W.; Nichols, Monte C., eds. (29 January 1990). "Skutterudite" (PDF). Handbook of Mineralogy. Vol. III (Halides, Hydroxides, Oxides). Chantilly, VA: Mineralogical Society of America. ISBN 0962209724. Retrieved 20 October 2024.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b "Skutterudite". Mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. 2025. Retrieved May 29, 2025.

- ^ Dana, James Dwight; Klein, Cornelis; Hurlbut, Cornelius S. (1985). Manual of Mineralogy (after James D. Dana). New York Chichester Brisbane [etc.]: J. Wiley and sons. p. 289. ISBN 0-471-80580-7 – via the Internet Archive.

- ^ Kraft, Alexander (August 2019), "Dorothea Juliana Wallich (1657–1725) and Her Contributions to the Chymical Knowledge about the Element Cobalt", Women in Their Element, World Scientific, pp. 57–69, doi:10.1142/9789811206290_0002, ISBN 978-981-12-0628-3, retrieved 2025-05-29

- ^ Cavallo, Giovanni; Riccardi, Maria Pia (November 2021). "Glass-based pigments in painting: smalt blue and lead–tin yellow type II". Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences. 13 (11). doi:10.1007/s12520-021-01453-7. ISSN 1866-9557.

- ^ Uher, Ctirad (2021-04-27). Thermoelectric Skutterudites (1 ed.). Boca Raton : CRC Press, 2021.: CRC Press. pp. xi. doi:10.1201/9781003105411. ISBN 978-1-003-10541-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Walker, T. L. (1921-03-01). "Skutterudite from Cobalt, Ontario1". American Mineralogist. 6 (3): 54–56. ISSN 0003-004X.

- ^ Oen, S; Dunn, P. J.; Kieft, C. (1984). "The nickel-arsenide assemblage from Franklin, New Jersey: description and interpretation". Neues Jahrbuch für Mineralogie. Abhandlungen. 150 (3): 259–272. ISSN 0077-7757.

- ^ Nolas, G. S., Morelli, D. T., Tritt, T. M. (1999). "SKUTTERUDITES: A Phonon-Glass-Electron Crystal Approach to Advanced Thermoelectric Energy Conversion Applications". Annual Review of Materials Science. 29 (1): 89–116. Bibcode:1999AnRMS..29...89N. doi:10.1146/ANNUREV.MATSCI.29.1.89. ISSN 0084-6600.

- ^ Oftedal, I. (1926). "The crystal structure of skutterudite and related minerals" (PDF). Norsk Geologisk Tidsskrift. 8: 250–257. Retrieved 13 March 2022.

- ^ Zhang, Shuye; Xu, Sunwu; Gao, Hui; Lu, Qingshuang; Lin, Tiesong; He, Peng; Geng, Huiyuan (January 2020). "Characterization of multiple-filled skutterudites with high thermoelectric performance". Journal of Alloys and Compounds. 814: 152272. doi:10.1016/j.jallcom.2019.152272.

- ^ Uher, Ctirad (2022). "Skutterudites: Prospective novel thermoelectrics". Semiconductors and Semimetals. Vol. 111. Elsevier. doi:10.1016/bs.semsem.2022.08.004. ISBN 978-0-323-98933-6. Retrieved 29 May 2025.

- ^ Nieroda, P.; Kutorasinski, K.; Tobola, J.; Wojciechowski, K. T. (June 2014). "Search for Resonant-Like Impurity in Ag-Doped CoSb3 Skutterudite: Theoretical and Experimental Study". Journal of Electronic Materials. 43 (6): 1681–1688. doi:10.1007/s11664-013-2833-3. ISSN 0361-5235.

- ^ Volja, Dmitri; Kozinsky, Boris; Li, An; Wee, Daehyun; Marzari, Nicola; Fornari, Marco (2012-06-22). "Electronic, vibrational, and transport properties of pnictogen-substituted ternary skutterudites". Physical Review B. 85 (24). arXiv:1112.1749. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.85.245211. ISSN 1098-0121.

- ^ Laufek, F.; Navrátil, J.; Plášil, J.; Plecháček, T.; Drašar, č. (June 2009). "Synthesis, crystal structure and transport properties of skutterudite-related CoSn1.5Se1.5". Journal of Alloys and Compounds. 479 (1–2): 102–106. doi:10.1016/j.jallcom.2009.01.067.

- ^ Salvador, James R; Cho, Zuxin Ye; Moczygemba, Joshua E; Thompson, Alan J; Sharp, Jeffrey W; König, Jan D; Maloney, Ryan; Thompson, Travis; Sakamoto, Jeffrey; Wang, Hsin; Wereszczak, Andrew A; Meisner, Gregory P (5 Oct 2012). "Thermal to Electrical Energy Conversion of Skutterudite-Based Thermoelectric Modules". Journal of Electronic Materials. 42 (7): 1389–1399. doi:10.1007/s11664-012-2261-9. S2CID 93808796.

- ^ Nolas, G. S., Slack, G. A., Morelli, D. T., Tritt, T. M., Ehrlich, A. C. (1996). "The effect of rare-earth filling on the lattice thermal conductivity of skutterudites". Journal of Applied Physics. 79 (8): 4002–4008. Bibcode:1996JAP....79.4002N. doi:10.1063/1.361828. ISSN 0021-8979.

- ^ Gharleghi, Ahmad; Pai, Yi-Hsuan; Fei-Hung, Lina; Liu, Chia-Jyi (17 Mar 2014). "Low thermal conductivity and rapid synthesis of n-type cobalt skutterudite via a hydrothermal method". Journal of Materials Chemistry C. 2 (21): 4213–4220. doi:10.1039/C4TC00260A. S2CID 97681877.

- ^ Sales, B. C.; Mandrus, D.; Williams, R. K. (1996-05-31). "Filled Skutterudite Antimonides: A New Class of Thermoelectric Materials". Science. 272 (5266): 1325–1328. doi:10.1126/science.272.5266.1325. ISSN 0036-8075.

- ^ Nolas, G. S.; Kaeser, M.; Littleton, R. T.; Tritt, T. M. (2000-09-18). "High figure of merit in partially filled ytterbium skutterudite materials". Applied Physics Letters. 77 (12): 1855–1857. doi:10.1063/1.1311597. ISSN 0003-6951.