Soup

| |

| Main ingredients | Liquid, meat or vegetables |

|---|---|

| Variations | Clear soup, thick soup |

Soup is a primarily liquid food, generally served warm or hot – though it is sometimes served chilled – made by cooking or otherwise combining meat or vegetables with stock, milk, or water. According to The Oxford Companion to Food, "soup" is "the most general of the terms which apply to liquid savoury dishes";[1] others include broth, bisque, consommé, potage and many more.

The consistency of soups varies from thin to thick: some soups are light and delicate; others are so substantial that they verge on being stews. Although most soups are savoury, sweet soups are familiar in some parts of Europe.

Soups have been made since prehistoric times, and have evolved over the centuries. Originally "sops" referred to pieces of bread covered with savoury liquid; gradually the term "soup" was transferred to the liquid itself. Soups are common to the cuisines of all continents and have been served at the grandest of banquets as well as in the poorest peasant homes. Some soups from Asia have become familiar in the west, but others remain almost entirely exclusive to their region of origin.

Name

The term soup, or words like it, can be found in many languages. Similar terms include the Italian zuppa, the German Suppe, the Danish suppe the Russian суп (pronounced "soup"), the Spanish sopa and the Polish zupa.[1] Other terms embraced by "soup" include broth, bisque, consommé, potage and many more.[1]

According to the lexicographer John Ayto, "the etymological idea underlying the word soup is that of 'soaking'". In his 2012 The Diner's Dictionary Ayto writes that the word dates back to an unrecorded post-classical Latin verb suppare – "to soak", which was derived from the prehistoric Germanic root "sup–", which also produced the English "sup" and "supper". The term passed into Old French as soupe, meaning a piece of bread soaked in liquid" and, by extension, "broth poured on to bread".[2] The ancient conjunction of bread and soup still exists not only in the croutons often served with soup, and the slice of baguette and Gruyère floating on traditional French onion soup, but also in bread-based soups including the German Schwarzbrotsuppe (black bread soup), the Russian Okroshka and the Italian pappa al pomodoro (tomato pulp).[3] The Dictionnaire de l'Académie française records the term "soupe" in French use from the twelfth century but adds that it is probably earlier.[4] The Oxford English Dictionary records the use of the word in English in the fourteenth century: "Soppen nim wyn & sucre & make me an stronge soupe",[5] but the first known cookery book in English, The Forme of Cury, c. 1390, refers to several "broths", but not to soups.[6]

The Oxford Companion to Food (OCF) comments that soups can stray, "over what is necessarily an imprecisely demarcated frontier", into the realm of stews. The Companion adds that this tendency is noticeable among fish soups such as bouillabaisse.[1] The Hungarian goulash is regarded by many as a stew but by others, particularly in Hungary, as a soup (Gulyás).[7] The food writer Harold McGee contrasts soups with sauces in On Food and Cooking, commenting that they can be so similar that soups may only be distinguished as less intensely flavoured, permitting them to be "eaten as a food in themselves, not an accent."[8]

History

Prehistory

The cooking of soup or something akin can be dated back to the Upper Palaeolithic period.[9][10] Small boiling pits are present on the Gravettian site Pavlov VI.[11] Some archaeologists conjecture that early humans employed hides and watertight baskets to boil liquids.[12]

Ancient times and later

In 1988 the food writer M. F. K. Fisher commented, "It is impossible to think of any good meal, no matter how plain or elegant, without soup or bread in it. It is almost as hard to find any recorded menu, ancient or modern, without one or both".[13] In her 2010 work Soup: A Global History, Janet Clarkson writes that the ancient Romans had a great variety of soups. De re coquinaria (On the Subject of Cooking), a collection of Roman recipes compiled in the fourth or fifth century from earlier manuscripts gives details of numerous ingredients, mostly vegetable.[14]

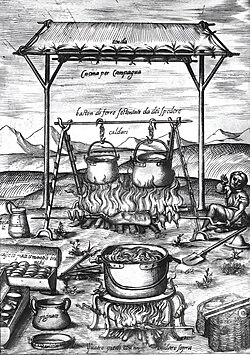

After the fall of the Roman Empire soups continued to feature in European and Arab cuisines. Clarkson writes that the earliest known German cookery book, Ein Buch von guter Spise (A Book of Good Food) published in about 1345, includes recipes for many soups, including one made with beer and caraway seeds, another with leeks, almond milk and rice meal, others with carrots and almond milk or goose cooked in broth with garlic and saffron. The early fifteenth-century French book Du fait de Cuisine (From the Kitchen) has many recipes for potages and "sops" including several regional variants.[15]

During the seventeenth century the soup itself, rather than the "sops" it contained, became seen as the most important element of the dish.[16] One of the most famous cookery books of its time was Robert May's The Accomplisht Cook (1660). Clarkson comments that about a fifth of May's recipes are for soups of one kind or another.[17]

In the eighteenth century, meals at grand European tables were still served in the style that had persisted since the Middle Ages, with successive courses of three or four dishes placed on the table simultaneously and then replaced by three or more contrasting dishes.[18] Soup was typically part of the first course. Exceptionally, at particularly grand dinners, a first course might consist of four different soups, succeeded by four dishes of fish and then four of meat.[n 1] In the early nineteenth century a new style of dining became fashionable in Europe and elsewhere: service à la russe – Russian-style service: dishes were served one at a time, usually beginning with soup.[18]

Asia

In Asian countries soup became a familiar breakfast dish, but has not, according to Clarkson, done so in the west.[20][n 2] In China and Japan, soup came to have a different place in meals. As in the west, there was a distinction between thick and thin soups, but the latter would often be treated as a beverage, to be drunk from the bowl rather than eaten with a spoon.[22] In Japan miso soup became the best known of the thick type, with many variations on the basic theme of dashi, a stock made from kombu (edible seaweed) and dried fermented tuna, with miso (fermented soy bean) paste. Clarkson writes, "Miso soup is the traditional breakfast soup in the ordinary home, and the traditional end to a formal banquet".[22] In China, soups wholly unknown in the west were developed, including bird's nest and shark's fin soups.[23] Snake soup continues to be an iconic tradition in Cantonese culture, and that of Hong Kong.[24] In China, rat soup is considered equal to oxtail soup.[25]

Indian cuisine includes rasam (sometimes called pepper-water), a thin, spicy soup, typically made with lentils, tomatoes, and seasonings including tamarind, pepper, and chillies.[26] In Thai cuisine gaeng chud are soups: the most popular are tom yum kung made with prawns and tom khaa gai made from galangal, chicken and coconut milk.[27] Pho is a Vietnamese soup, usually made from beef stock and spices with noodles and thinly sliced beef or chicken added.[28] In Filipino cookery sinigang is a soup made with meat, shrimp, or fish and flavoured with a sour ingredient such as tamarind or guava;[29] also from the Philippines is caldereta, a goat soup.[30] The soups of Indonesia include soto ayam (chicken), sop udang (shrimp with rice vermicelli) and soto dengan keptiting (crab).[31] Garudhiya is a soup served in the Maldives, with chunks of tuna in it.[32]

Two soups from Armenia are a cucumber and yoghurt soup called jajik, and bozbash, containing lamb and fruit;[33] dyushbara is a dumpling soup from Azerbaijan;[34] Tibetan cooking includes tsamsuk, made from grains, butter, soya and cheese.[35]

Europe and the Americas

(William-Adolphe Bouguereau, 1865)

In the OCF Alan Davidson writes that although soup is now typically served as the first of several courses in western menus, in many places around the world substantial soups have historically been an entire meal for poorer people, particularly in rural areas.[1] Many Russian peasants subsisted on rye bread and soup made from pickled cabbage.[36] Charitable soup-kitchens preparing soup and supplying it to the needy, either free or at a very low charge,[37] were known in the Middle East in the sixteenth century. From the late eighteenth century, soup-kitchens (in German Suppenküche, in French, soupes populaires) were set up in Germany, England and France and elsewhere. In the 1840s the chef Alexis Soyer established a soup-kitchen in the East End of London to feed Huguenot silk weavers impoverished by cheap imports.[38] During the Irish famine, which began in 1845, he set up a kitchen in Dublin capable of feeding a thousand people an hour.[39] In the United States soup-kitchens were set up in the 1870s. During the Great Depression, Al Capone established and sponsored a soup-kitchen in Chicago.[40]

From the sixteenth century onwards, Paris was known for its street vendors selling soup,[n 3] and in mid-nineteenth-century Paris, Les Halles, the large food market, became known for its stalls selling onion soup with a substantial topping of grated cheese, put under a grill and served au gratin.[42][43] According to one writer, the classic gratinée des Halles transcended class distinctions:

The many cuisines of Europe have a wide range of soups. Among the soups of Italy are minestrone, zuppa pavese and straciatella, respectively a vegetable broth, consommé with poached eggs, and a meat broth with eggs and cheese.[45] From Belgium there are potage liégeois – a pea and bean soup – and soupe tchantches, a vegetable soup with fine vermicelli and milk.[46] Bulgarian cuisine includes tarator, a cold yoghurt and cucumber soup[47] Dutch soups include erwtensoep – a split pea soup – and bruinebonensoep, a brown bean soup eaten with rye bread and bacon.[48] A soup from the Faeroe Islands is raskjøt, made with dried mutton.[49] Erbensuppe mit Schweinsohren, is a German split pea soup with pig's ear.[50] Zivju supa, a Latvian fish soup incorporates whole pieces of cooked fish with potato;[51] The Finnish kesäkeitto is a light summer soup of seasonal vegetables cooked in milk and water;[52] the Swedish köttsoppa is a meat and vegetable soup;[53] the Norwegian blomkålspuré is cauliflower soup with egg yolks and cream.[52] Gehdck, from Luxembourg, is made with pork offal, and finished with prunes soaked in local white wine.[54]

Maltese soups include soppa tal-armla ("widow's soup"), made with green and white vegetables and garnished with a poached egg and cheese, and aljotta a light fish soup flavoured with garlic and marjoram.[55] two soups from Poland are chlodnik, a crayfish and beetroot soup, served chilled[56] and grochowka, yellow-pea soup with barley.[57] Portuguese soups include canja (chicken) and caldo verde (potato and cabbage).[58] Cullen skink (smoked haddock soup)[59] and nettle soup[60] are of Scottish origin. A Welsh soup, cawl, is typically made with lamb or beef together with vegetables including potatoes, swedes and carrots.[61] Slovenian cuisine includes juha, a meat and vegetable soup.[62] Russian soups include schi (cabbage soup), solyanka (vegetable soup with meat or fish), rassolnik (pickled cucumber soup), and ukha (fish soup).[63]

Soups from the Americas include a spiny lobster soup from Belize,[64] Cajun crayfish bisque,[65] and gumbo, a hearty soup (or stew) traditionally made from meat or shellfish with tomatoes, vegetables, herbs, and spices, thickened with okra.[66] In the Caribbean and Latin America sancocho is a thick soup typically consisting of meat, tubers, and other vegetables.[67] Callalloo soups are found in the West Indies and Brazil;[68] ajiaco Santaferenio is a Colombian avocado soup),[69] and Mexico has a black bean soup.[70] Honduras and the US both have a tripe soup, the former called mondongo and the latter pepper pot soup.[71] The clam chowder of New England has entered the international culinary repertoire.[72]

Other cuisines

Arab shorba typically contains meat and oats;[73] Egyptian food includes melokhia soup.[74] An Iranian summer soup, mast-o khiar, is made with yoghurt, cucumber, and mint.[75] The Moroccan harira contains chickpeas, meat and rice.[76] Turkish kelle-paça is made from the meat from animal heads and feet.[77] In Nigeria, according to Davidson, "soupy stews or stewlike soups" are popular. He gives as examples egusi soup, often made with offal, palm oil, carob, lemon basil, and egusi powder, and various okra soups. He adds that in Nigeria soup made from goat is "so important that it is usually served at the most important functions".[78] Australasian soups include toheroa (clam) soup from New Zealand,[79] and the Australian wallabi-tail soup.[80]

Modern times

In the western cuisine of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries there have been and are numerous soups. Auguste Escoffier divided them into two main types:

- Clear soups, which include plain and garnished consommés

- Thick soups, which comprise the purées, veloutés, and creams

He added, "A third class, which is independent of either of the above, in that it forms part of plain, household cookery, embraces vegetable soups and garbures or gratinéd soups. But in important dinners – by this I mean rich dinners – only the first two classes are recognised".[81]

Louis Saulnier's Le Répertoire de la cuisine, first published in 1914, contains six pages of details of potages (clear soups), two pages on soupes (moistened with water, milk or thin white stock), eight pages on veloutés (soups thickened with egg yolks) and crèmes (thickened with double cream),[82] as well as a further three pages on fifty-three "Potages étrangers" – foreign soups – including borscht from Russia, clam chowder from the United States, cock-a-leekie from Scotland, minestrone from Italy, mock turtle from England, and mulligatawny from British India.[83]

The French distinction between clear and thick soups is echoed in other languages: in German Klare Suppen and Gebundene Suppen; in Italian Brodi and Zuppe; and in Spanish Sopas claras and Sopas spessas.[84] Many soups are fundamentally the same in the cuisines of various countries, with minor local variations. Oxtail soup, a familiar item in British and American cooking, is one of several oxtail soups from round the world, including one from Sichuan, others from Austria (Ochsenschleppsuppe), Jamaica, and the French potage bergére, oxtail consommé thickened with tapioca, garnished with asparagus and diced mushrooms.[85]

Elizabeth David comments in French Provincial Cooking (1960), "No doubt because the tin and the package have become so universal, people are astonished by the true flavours of a well-balanced home-made soup and demand more helpings if only to make sure that their noses and palates are not deceiving them".[86] In their Mastering the Art of French Cooking (1961), Simone Beck, Louisette Bertholle and Julia Child write:

Cold soups

Cold soups are a particular variation on the traditional soup. Two well-known chilled soups are the Franco-American vichyssoise and the Spanish gazpacho. The Oxford English Dictionary defines the former as "A soup made with potatoes, leeks, and cream, usually served chilled", and the latter as "A cold Spanish vegetable soup consisting of onions, cucumbers, pimentos, etc., chopped very small with bread and put into a bowl of oil, vinegar, and water".[88]

Sweet soups

Fruit soups are well known in Germany and Nordic countries. Although they may sometimes be served at the beginning of a meal they are sweet dishes. Davidson instances rødgrød, also known as rote Grütze, a red berry soup popular in Denmark, other parts of Scandinavia and Germany, sitruunakeitto, a creamy lemon soup from Finland, and the Middle Eastern khoshab, made with dried fruits. Other fruits used to make sweet soups include apples, blueberries, cherries, gooseberries, rhubarb and rose-hips.[89]

Sour soups

Davidson mentions a category, "sour soups", important in northern, eastern and central Europe. Some have a fermented beer base or use Sauerkraut, others are soured with vinegar, pickled beetroot, lemon or yoghurt. Examples include sinisang (above), chorba, a meat and vegetable soup found in many coutries of eastern Europe, north Africa and Asia,[90] and sop ikan pedas, a fish soup from Indonesia.[91]

Portable, tinned and dried soups

Food preservation has, in Clarkson's phrase, "always been a preoccupation of the human animal",[92] allowing food to be kept for long periods. In her Domestic Cookery (1806), Maria Rundell gave a recipe for "Portable Soup – a very useful thing"[93] – highly concentrated meat stock that set to a solid consistency: for a bowl of soup it was only necessary to dissolve some in hot water.[94] By the beginning of the nineteenth century the Royal Navy had been victualling its ships with portable soup for some years.[95] Recipes were published under many names; Clarkson lists "veal glew", "cake soup", "cake gravey", "broth cakes", "solid soop", "portmanteau pottage", "pocket soup", "carry soup and "soop always in readiness".[96]

In 1810 an English inventor called Peter Durand was granted a patent for the first tin can for soup. The first commercial canning factory opened in England in 1813; it had a capacity of only six cans an hour; each can was cut by hand, filled and the lid soldered on individually.[97] With advances in technology the canning of food had expanded by the end of the century and companies such as Heinz were promoting their soups as gourmet products indistinguishable from home-made versions.[98] In 1897 Heinz's rival Campbell's introduced condensed canned soups, to be diluted with water to produce double the volume.[n 4] The first five soups in Campbell's range were tomato, chicken, oxtail, consommé, and vegetable.[100] According to the food historian Reay Tannahill, tomato soup did not become popular in the US or Britain until then.[101]

Drying is one of the oldest methods of preserving food, and in the nineteenth century Soyer praised commercially dried vegetables as a good ingredient of soldiers' soup during the Crimean War.[102] Dried soups remained in military use into the 1950s, but it was not until the mid-twentieth century that manufacturers began extensively marketing them for domestic use. The Good Nutrition Guide (2008) commented, "Although many types of processed soup have been criticised for their salt levels, packet soups are by far the worst".[103] Subsequently, some manufacturers have experimented with reduced-salt packet soups. A trial in France in 2012 found that reducing salt in chicken noodle soup by more than thirty per cent did not affect consumers' liking for the product.[104]

Gallery

-

Chicken phở

-

Vegetable beef barley soup

-

Chicken pasta soup

-

Chunky tomato soup

Notes, references and sources

Notes

- ^ For a dinner given by the Prince Regent in 1817, Antonin Carême served a first course of Potage à la Monglas, Garbure aux choux, Potage d'orge perlée à la Crécy and Potage de poisons à la russe (respectively, a brown cream soup with foie gras and truffles, rustic vegetable broth with cabbage, a delicate purée of pearl barley and carrots, and Russian style fish soup).[19]

- ^ Nevertheless, the creator of vichyssoise, Louis Diat recalled in his memoirs, published in 1961: "Casting about one day for a new cold soup, I remembered how maman used to cool our breakfast soup, on a warm morning, by adding cold milk to it. A cup of cream, an extra straining, and a sprinkle of chives, et voila, I had my new soup. I named my version of maman's soup after Vichy, the famous spa located not twenty miles from our Bourbonnais home, as a tribute to the fine cooking of the region".[21]

- ^ In 1765, according to Prosper Montagné's Larousse Gastronomique, a Parisian entrepreneur opened a shop specialising in soups. This prompted the use of the modern word restaurant to refer to eating establishments.[41]

- ^ To sell condensed soup at low prices, Campbell's management drove down costs by automating production as much as possible and applying anti-union policies against the workforce.[99]

References

- ^ a b c d e Davidson, p. 735

- ^ Ayto, p. 344

- ^ Clarkson, pp. 90–91

- ^ "soupe", Dictionnaire de l'Académie française. Retrieved 14 June 2025

- ^ "soup". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Clarkson, pp. 26–27

- ^ Bickel, p. 426; and Grigson, p. 308

- ^ McGee, p. 581

- ^ Wu, X.; Zhang, C.; Goldberg, P.; Cohen, D.; Pan, Y.; Arpin, T.; Bar-Yosef, O. (2012). "Early Pottery at 20,000 Years Ago in Xianrendong Cave, China". Science. 336 (6089): 1696–1700. Bibcode:2012Sci...336.1696W. doi:10.1126/science.1218643. PMID 22745428. S2CID 37666548.

- ^ Speth, John D. (5 September 2014). "When Did Humans Learn to Boil?" (PDF). Paleoanthropology Society. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 October 2022. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ^ Svoboda, Jiří A. (30 December 2007). "The Gravettian on the Middle Danube". PALEO. Revue d'archéologie préhistorique (19): 203–220. doi:10.4000/paleo.607. ISSN 1145-3370. Archived from the original on 30 December 2022. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ^ Nelson, Kit (1 June 2010). "Environment, cooking strategies and containers". Journal of Anthropological Archaeology. 29 (2): 238–247. doi:10.1016/j.jaa.2010.02.004. ISSN 0278-4165.

- ^ Fisher, p. 34

- ^ Clarkson, p. 26

- ^ Clarkson, p. 27

- ^ Tannahill, p. 237

- ^ Clarkson, p. 29

- ^ a b Clarkson, p. 30

- ^ Tannahill, pp. 298–299

- ^ Clarkson, pp. 107–108

- ^ Diat, p. 59

- ^ a b Clarkson, p. 106

- ^ Clarkson, pp. 106–107

- ^ Landry Yuan, Félix et al. "Conservation and Cultural Intersections within Hong Kong’s Snake Soup Industry", Oryx 57.1 (2023), p. 40

- ^ Davidson and Jaine, p. 673

- ^ "rasam". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Davidson, p. 791

- ^ "pho". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ "sinigang". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Davidson, p. 342

- ^ Anderson, pp. 18–20 and 24

- ^ Davidson and Jaine, p. 487

- ^ Davidson, p. 35

- ^ Davidson, p. 44

- ^ Davidson, p. 808

- ^ Tannahill, p. 251

- ^ "soup-kitchen". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Cowen, pp. 120–121

- ^ Ray, Elizabeth. "Soyer, Alexis Benoît (1810–1858)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2011. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- ^ Clarkson, p, 57

- ^ Montagné, p. 764

- ^ " Dégustation : la soupe à l'oignon, bonne à en pleurer!", Le Parisien, 21 January 2015. Retrieved 27 August 2023

- ^ Briffault, p. 155

- ^ "French Onion Soup", World in Paris, 2016. Retrieved 27 August 2023

- ^ David (1987), pp. 53 and 58–61

- ^ Davidson, p. 71

- ^ Davidson, p. 783

- ^ Davidson and Jaine, p. 550

- ^ Davidson, p. 286

- ^ Davidson, p. 265

- ^ Davidson, p. 445

- ^ a b Bonekamp, p. 27

- ^ Bonekamp, p. 25

- ^ Davidson, p. 464

- ^ Davidson and Jaine, p. 489

- ^ Davidson, p. 175

- ^ Davidson, p. 615

- ^ Davidson and Jaine, p. 644

- ^ Davidson, p. 233

- ^ Davidson, p. 531

- ^ "cawl". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Davidson and Jaine, pp. 746–746

- ^ "schi". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.); "solyanka". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.); "rassolnik". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.); "ukha". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Davidson, p. 151

- ^ Davidson, p. 122

- ^ "gumbo". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ "scancocho". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Davidson, p. 125

- ^ Davidson and Jaine, p. 208

- ^ Davidson, p. 371

- ^ Davidson, pp. 151 and 596

- ^ Saulnier, p. 51

- ^ Davidson, p. 32

- ^ Davidson, p. 257

- ^ Davidson and Jaine, p. 415

- ^ Davidson, p. 515

- ^ Davidson, p. 294

- ^ Davidson, p. 842

- ^ Davidson and Jaine, p. 552

- ^ Davidson, p. 40

- ^ Escoffier, p. 197

- ^ Saulnier, pp. 33–50

- ^ Saulnier, pp. 50–53

- ^ Bickel, p. 59

- ^ Davidson, p. 562; Hess and Hess, p. 14; Scala Quinn, p. 61; and Saulnier, p. 33

- ^ David (2008), p. 136

- ^ Beck et al, p. 35

- ^ "vichyssoise". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.);"gazpacho". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Davidson, p. 323

- ^ Davidson, p. 736

- ^ Anderson, p. 23

- ^ Clarkson, p. 67

- ^ Rundell, pp. 101–102

- ^ Tannahill, p. 229

- ^ Clarkson, p. 70

- ^ Clarkson, p. 68

- ^ Clarkson, p. 81

- ^ Clarkson, p. 83

- ^ Stanger, Howard R. "Condensed Capitalism: Campbell Soup and the Pursuit of Cheap Production in the Twentieth Century". Business History Review 85.2 (2011), p. 419

- ^ Genovese, p. 174

- ^ Tannahill, p. 207

- ^ Clarkson, p. 76

- ^ Edwardes, p. 234

- ^ Willems, Astrid A. et al. "Effects of Salt Labelling and Repeated In-Home Consumption on Long-Term Liking of Reduced-Salt Soups", Public Health Nutrition 17.5 (2014), p. 1130

Sources

- Anderson, Susan (1995). Indonesian Flavors. Berkeley: Frog. ISBN 1-883319-28-5.

- Ayto, John (2012). The Diner's Dictionary: Word Origins of Food & Drink (second ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-174443-3.

- Beck, Simone; Louisette Bertholle; Julia Child (2012) [1961]. Mastering the Art of French Cooking, Volume One. London: Particular. ISBN 978-0-241-95339-6.

- Bickel, Walter (1989). Hering's Dictionary of Classical and Modern Cookery (eleventh ed.). London: Virtue. ISBN 978-3-8057-0307-9.

- Bonekamp, Gunnevi (1973). Scandinavian Cooking. New York: Drake. OCLC 1036846656.

- Briffault, Eugène (2018). Paris à table 1846. Oxford: Oxford Universtiry Press. ISBN 978-0-19-084203-1.

- Clarkson, Janet (2010). Soup: A Global History. London: Reaktion. ISBN 978-1-86-189890-6.

- Cowen, Ruth (2006). Relish: The Extraordinary Life of Alexis Soyer, Victorian Celebrity Chef. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-297-64562-7.

- David, Elizabeth (1987) [1954]. Italian Food. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-046841-0.

- David, Elizabeth (2008) [1960]. French Provincial Cooking. London: Folio Society. OCLC 809349711.

- Davidson, Alan (1999). The Oxford Companion to Food (first ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-211579-9.

- Davidson, Alan (2014). Tom Jaine (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Food (third ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-967733-7.

- Diat, Louis (1979) [1961]. Gourmet's Basic French Cookbook: Techniques of French Cuisine. New York: Gourmet Books. OCLC 1246316969.

- Edwardes, Sarah (2008). The Good Nutrition Guide. London: Ethical Marketing Group. ISBN 978-0-95-529072-5.

- Escoffier, Auguste (1907). A Guide to Modern Cookery. London: Heinemann. OCLC 1097154246.

- Fisher, M. F. K. (1988). Dubious Honors. San Francisco: North Point Press. OCLC 17926657.

- Genovese, Peter (2007). New Jersey Curiosities. Guilford: Globe Pequot Press. ISBN 978-0-76-274112-0.

- Grigson, Sophie (2009). The Soup Book. London: Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 978-1-40-534785-3.

- Hess, Olga; Adolf Franz Hess (1977). Wiener Küche (in German). Vienna: Deuticke. ISBN 3-70-054406-5.

- McGee, Harold (2004). On Food and Cooking (2nd ed.). New York: Scribner. ISBN 1-4165-5637-0.

- Montagné, Prosper (1977). The New Larousse Gastronomique. London: Hamlyn. ISBN 978-0-60-036545-7.

- Rundell, Maria (1806). A New System of Domestic Cookery. London: John Murray. OCLC 970770908.

- Saulnier, Louis (1978) [1914]. Le répertoire de la cuisine (fourteenth ed.). London: Jaeggi. OCLC 1086737491.

- Scala Quinn, Lucinda (2006). Lucinda's Authentic Jamaican Kitchen. Hoboken: Wiley. ISBN 978-0-47-174935-6.

- Tannahill, Reay (2002). Food in History. London: Hodder. ISBN 0-7472-6796-0.

See also

- Lists of foods

- List of bean soups

- List of fish and seafood soups

- Soup and sandwich

- Soup spoon

- Stone Soup

- Three grand soups

Further reading

- Fernandez-Armesto, Felipe. Near a Thousand Tables: A History of Food (2002). New York: Free Press ISBN 0-7432-2644-5

- Jennifer Harvey Lang, ed., Larousse Gastronomique, American Edition (1988). New York: Crown Publishers ISBN 0-609-60971-8

- Morton, Mark. Cupboard Love: A Dictionary of Culinary Curiosities (2004). Toronto: Insomniac Press ISBN 1-894663-66-7

- Rumble, Victoria R. (2009). Soup Through the Ages. McFarland. ISBN 9780786439614.

- Van Dyk, Garritt C. (4 June 2023). "'Good soup is one of the prime ingredients of good living': a (condensed) history of soup, from cave to can". The Conversation. Retrieved 28 July 2024.