Suzhou dialect

| Suzhounese | |

|---|---|

| 蘇州閒話;苏州闲话 Sou-tseu ghé-ghô | |

| Pronunciation | [soʊ˥tsøʏ˥꜓ ɦɛ˨˨˧꜕ɦo˨˧˩꜔] or [soʊ˥tsøʏ˥꜓ ɦɛ˨˨˦꜔ɦo˨˧˩꜕꜖] |

| Native to | China |

| Region | Suzhou and southeast Jiangsu province |

| Chinese characters | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| ISO 639-6 | suji |

wuu-suh | |

| Glottolog | suzh1234 |

| Linguasphere | 79-AAA-dbb |

| Suzhou dialect | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 蘇州話 | ||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 苏州话 | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 蘇州閒話 | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

Suzhounese (Suzhounese: 蘇州閒話; sou1 tseu1 ghe2 gho6), also known as the Suzhou Language, is the language belonging to the Sinitic Language Family traditionally spoken in the city of Suzhou in Jiangsu, China. Suzhounese is a dialect of Wu Chinese, and was traditionally considered the Wu Chinese prestige dialect. Suzhounese has a large vowel inventory and it is relatively conservative in initials by preserving voiced consonants from Middle Chinese.[citation needed]

Distribution

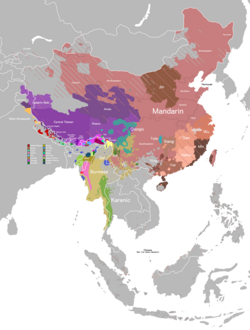

[edit]Suzhou dialect is spoken within the city itself and the surrounding area, including migrants living in nearby Shanghai.

The Suzhou dialect is mutually intelligible with dialects spoken in its satellite cities such as Kunshan, Changshu, and Zhangjiagang, as well as those spoken in its former satellites Wuxi and Shanghai. It is also partially intelligible with dialects spoken in other areas of the Wu cultural sphere such as Hangzhou and Ningbo. However, it is not mutually intelligible with Cantonese or Standard Chinese; but, as all public schools and most broadcast communication in Suzhou use Mandarin exclusively, nearly all speakers of the dialect are at least bilingual. Owing to migration within China, many residents of the city cannot speak the local dialect but can usually understand it after a few months or years in the area.[citation needed]

History

[edit]This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (October 2022) |

Grammar

[edit]| Pronoun | Number | Word | Pinyin | IPA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | Singular | 吾 | ngou6 | ŋəu |

| Plural | 伲 | gni6 | nʲi | |

| 2nd | Singular | 倷 | ne6 | ne |

| Plural | 唔笃 | n6 toq7 | n toʔ | |

| 3rd | Singular | 俚 | li1 | li |

| 俚倷 | li1 ne6 | li ne | ||

| 唔倷 | n1 ne6 | n ne | ||

| Plural | 俚笃 | li1 toq7 | li toʔ |

Second and third-person pronouns are suffixed with 笃 [toʔ] for the plural. The first-person plural is a separate root, 伲 [nʲi].[3]

Demonstrative

[edit]| Proximal | Neutral | Distal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 哀 | e1 | 搿 | geq8 | 弯 | ue1 |

| 该 | ke1 | 归 | kue1 | ||

In the Suzhou dialect, geq8 /ɡəʔ/ [gə̯] is a very special demonstrative that is used alongside a separate set of proximal and distal demonstratives. geq8 can indicate referents appearing in a speech situation, which may be close to or far away from the deictic center, and under these conditions, geq8 is always used in combination with gestures. Hence geq8 can serve both proximal and distal functions.[4]

哀 with 该 and 弯 with 归 means exactly the same thing and only differ in pronunciation. The use of neutral demonstrative pronoun became clear once proximal and neutral demonstrative pronouns are used.

- 哀杯茶是吾葛,掰杯茶是僚葛,弯杯茶是俚葛。

When "搿" refers to time, there is no need to use the proximal and distal in opposition. The role of the neutral demonstrative is very obvious.

- 抗战是民国二十六年到民国三十四年,掰歇(弯歇)辰光日脚勿好过。

In this sentence, "掰歇(弯歇)" cannot be replaced by "哀歇" because the Anti-Japanese War happened more than fifty years ago, so only the neutral or distal demonstrative can be used, not proximal.

When not referring to time, the proximal "哀" and the neutral demonstrative "掰" can be interchanged. For example, the "掰" in "掰个人勿认得" can be replaced by "哀".

"哀", "该", "掰", "弯" and "归" cannot be used as subjects or objects alone, but must be combined with the following quantifiers, locative words, etc.

| Suzhou | Mandarin | English | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 哀葛 | e1 keq7 | 这个 | this (thing) |

| 哀点 | e1 tie3 | 这些 | these |

| 哀歇 | e1 shieq3 | 这时候 | this (moment) |

| 哀呛 | e1 tie3 | 这阵子 | this (period) |

| 哀面 | e1 mie6 | 这边 | this (side) |

| 哀搭 | e1 taeq7 | 这里 | this place (here) |

Example phrases:

- 哀歇啥辰光则?

现在什么时候了? What time is it now?

- 哀呛倷身体好啘?

现阵子你身体好吗? How are you now?

Varieties

[edit]Some non-native speakers of Suzhou speak the Suzhou dialect in a "stylized variety" to tell tales.[5]

Phonology

[edit]Initials

[edit]The Suzhou dialect has series of voiced, voiceless, and aspirated stops, and voiceless and voiced fricatives. Moreover, palatalized initials also occur.

Finals

[edit]| Front | Central | Back | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unrounded | Rounded | |||

| Apical | /ɿ/ | /ʮ/ | ||

| Fricated | /i/ | /y/ | /u/ | |

| Close | /ɪ/ | /ʏ/ | ||

| Near-close | /ɵ/ | /o/ | ||

| Mid | /ɛ/ | /ə/ | ||

| Open | /æ/ | /a/ | /ɑ/ | |

| Diphthong | /øʏ, oʊ/ | |||

| Coda | Open | Nasal | Glottal stop | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medial | ∅ | j | w | ∅ | j | w | ɥ | ∅ | j | w | ɥ | |

| Nucleus | ɿ [z̩] | z̩ | ||||||||||

| ʮ [z̩ʷ] | z̩ʷ | |||||||||||

| u | u | |||||||||||

| i | i | iɲ | ||||||||||

| y | y | |||||||||||

| ɪ | jɪ | |||||||||||

| ʏ | ʏ~øʏ | jʏ | ʏɲ | |||||||||

| ɵ | ɵ | jɵ | wɵ | |||||||||

| ɛ | ɛ | wɛ | ||||||||||

| ə | ən | wən | ɥən | əʔ | jəʔ | wəʔ | ɥəʔ | |||||

| o | o | jo | oŋ | joŋ | oʔ | joʔ | ||||||

| oʊ | oʊ | |||||||||||

| æ | æ | jæ | ||||||||||

| a | ã | jã | wã | aʔ | jaʔ | waʔ | ɥaʔ | |||||

| ɑ | ɑ | jɑ | wɑ | ɑ̃ | jɑ̃ | wɑ̃ | ɑʔ | jɑʔ | ||||

- Syllabic continuants: /ɿ/ [z̩] /ʮ/ [z̩ʷ] /u/ [β̩~v̩] [m̩] [ŋ̩] [l̩]

Notes:

- The Suzhou dialect has a rare contrast between "fricative vowels" [i, y] and ordinary vowels [ɪ, ʏ].

- /j/ is pronounced [ɥ] before rounded vowels.

- /ɛ/ is a true mid vowel, [ɛ̝]. May also be transcribed with the Sinological symbol /ᴇ/.

- In open syllables, /o/ is articulated close to a position for a close back vowel [o̝]

- Depending on the source, transcriptions differ:

- /oʊ/ may also be transcribed as /əu/

- /ɵ/ may also be transcribed as /ø/; also applies to on-glide final rhymes /jɵ/ (/iø/) and /wɵ/ (/uø/)

- /øʏ/ may also be transcribed as /ʏ/

- Close vowels /ɪ ʏ/ may be analyzed as diphthongs and transcribed as /iɪ iʏ/

Historical Finals

[edit]The Suzhou dialect allows a nasal coda but does not distinguish between them. As such, the Middle Chinese nasal codas *-m *-n *-ŋ have largely either merged or been lost depending on the vowel it follows. Historical *-ŋ rimes following certain vowels are distinguished as the nasalized vowels /ã ɑ̃/, but otherwise merge into modern /-n/. Historical *-n and *-m rimes are entirely merged and also result in modern /-n/, or are lost after certain vowels becoming modern /ɪ ɛ ɵ/. Modern /ɛ/ also results from the monophthongization of the historical diphthong rime *-ɑi (-oj in Baxter's notation, corresponding to the 咍 final).

Middle Chinese *-p *-t *-k rimes have become glottal stops, [-ʔ]. Like other Northern Wu varieties, syllables with an underlying glottal stop coda /-ʔ/ usually manifest as a shortening of the vowel instead of an actual glottal stop [-ʔ], unless before a pause or at the end of an utterance.

Tones

[edit]Suzhou is considered to have seven tones. However, since the tone split dating from Middle Chinese still depends on the voicing of the initial consonant. Yang tones are only found with voiced initials, namely [b d ɡ z v dʑ ʑ m n nʲ ŋ l ɦ], while the yin tones are only found with voiceless initials. These constitute just three phonemic tones: ping, shang, and qu. (Ru syllables are phonemically toneless.)

| Tone number | Wugniu Tone | Tone name | Tone letters | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | yin ping (阴平) | ˦ (44) | high |

| 2 | 2 | yang ping (阳平) | ˨˨˦ (224) | level-rising |

| 3 | 3 | shang (阴上) | ˥˨ (52) | high falling |

| 4 | 5 | yin qu (阴去) | ˦˩˨ (412) | dipping |

| 5 | 6 | yang qu (阳去) | ˨˧˩ (231) | rising-falling |

| 6 | 7 | yin ru (阴入) | ˦ʔ (4) | high checked |

| 7 | 8 | yang ru (阳入) | ˨˧ʔ (23) | rising checked |

In Suzhou, the Middle Chinese 阳上 tone and 阳去 tones have fully merged as (2)31. The original 阳去 313 tone possibly still occurs in tone sandhi patterns as the second element of a chain, following a 阴入 syllable[7] (though it could be analyzed differently; see Tone Sandhi section below).

Therefore, 买 and 卖 has exactly the same pronunciation in literary and colloquial readings 6ma /mɑ˨˧˩/

Tone Sandhi

[edit]Tone in Suzhou dialect, like other Northern Wu varieties is generally grouped by phrasal tone pattern, also called sandhi chains or sandhi domains.

An analysis by Wang (2011)[8] describes Suzhou tone sandhi as rightward tone-spreading of the left-most (i.e. initial) syllable of a phrase. Such described "left-prominent" phrases with non-checked initial syllables of a given length have one of five possible contours, each equivalent to each of the five tones. While generally described as rightward tone-spreading of the initial syllable, it is also common for the phrasal tone pattern to not be the same as that of the initial tone. This is currently the system used on Wiktionary entries with Suzhou data.

To distinguish the individual tone from the pattern expected from its tone spreading, the patterns themselves are referred to with the format of tone number + X (1x, 2x, 3x, etc).

| Initial syllable's tone | 2-syllable | 3-syllable | 4-syllable | Chain |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 陰平 44 | 4 0 歡喜 |

4 4 0 | 4 4 4 0 | 1x |

| 陽平 223 | 2 3 圍身 |

2 3 0 | 2 3 4 0 | 2x |

| 上聲 52 | 52 1 寫意 |

52 1 0 | 52 1 1 0 | 3x |

| 陰去 523 | 52 3 啥體 |

52 3 0 | 52 3 4 0 | 5x |

| 陽去 231 | 23 1 後日 |

23 1 0 | 23 1 1 0 | 6x (or 4x) |

A tone level of 0 in the above chart indicates a syllable with a neutral tone (轻声; 輕聲; qīngshēng; 'light tone'), functionally comparable to that of Standard Chinese. The surface realization at the end of an utterance is a low akin to downstep, but in flowing speech is a mid/neutral pitch or may appear to copy the previous tone target.

Additionally, Li (1998)[9] describes the 5x chain such that the second syllable has a slight rise. Li also describes a higher mid/high-level for the second syllable of a 6x chain.

| Tone pattern | 2-syllable | 3-syllable |

|---|---|---|

| 阳上式 (6x/4x) | 23 1 两人 |

23 44 21 同志们,碰碰看,五十岁 |

| 去声式 (5x) | 52 23 四首 |

52 23 21 解放军,打火机,卷心菜 |

In phrases with checked initial syllables, the first two tones determine the overall contour. The resulting contour can be summarized as retaining the tone class (平上去) of the second syllable, but not the voicing class (陰陽). Both Tone 1 陰平 /44/ and Tone 2 陽平 /223/ will result in a Tone 2 contour (/223/). Both Tone 5 陰去 /523/ and Tone 6 陽去 /231/ will result in a Tone 5 contour (/523/).

| First tone | Second tone | 2-syllable | 3-syllable | 4-syllable | Chain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 陰入 5 | 平聲 44 or 223 |

4 23 塌車 |

4 23 0 | 4 23 4 0 | 7.2 |

| 陽入 23 | 2 3 搿星 |

2 3 0 | 2 3 4 0 | 8.2 | |

| 陰入 5 | 上聲 52 | 5 51 則到 |

5 51 0 | 5 51 1 0 | 7.3 |

| 陽入 23 | 2 51 杌子 |

2 51 0 | 2 51 1 0 | 8.3 | |

| 陰入 5 | 去聲 523 or 231 |

5 523 搭檔 |

5 52 3 | 5 52 2 3 | 7.5 |

| 陽入 23 | 2 523 白菜 |

2 52 3 | 2 52 2 3 | 8.5 | |

| 陰入 5ˀ | 入聲 5ˀ or 23ˀ |

4 4 赤膊 |

4 4 0 | 4 4 2 0 | 7.7 |

| 陽入 23ˀ | 3 4 直腳 |

3 4 0 | 3 4 2 0 | 8.7 |

Ye 1988[10] describes additional patterns where

- Tone 7 阴入 + Tone 1/3/5 retaining full tone, resulting in a /5ˀ 5/ pattern if Tone 7 阴入 is followed by Tone 1 阴平

- the original un-merged Yangshang 阳去 313 tone still occurs as the second element of a chain, following a 阴入 syllable (7.6 chain).

- The second syllable of an 8x chain having a low-falling /21/ regardless of original tone

However, Wang describes the same phrases differently, and so it is debatable whether these form distinct patterns:

| Phrase | Wang 2011 | Ye 1988 |

|---|---|---|

| 菊花 cioq ho |

4 23 (p. 190) |

˥ˀ ˥ (~4ˀ 44) (p. 124, 366) |

| 綠豆 loq deu |

2 51 (p. 191) |

(~3ˀ 21) (p. 126, 361) |

| 赤豆 tshaq deu |

5 523 (p. 181) |

5 313 (p. 119) |

| 結冰 ciq pin |

4 23 (p. 182) |

5ˀ 5 (i.e. no change) (p. 124) |

Tone Category Shifts

[edit]As mentioned above, the tone pattern of a phrase frequently does not match the expected pattern based on the initial syllable's underlying tone.

Most frequently:

- a phrase beginning with a Tone 3 syllable takes on the tone pattern expected of a Tone 5 syllable (in other words, a 5x chain) or a Tone 1 syllable (a 1x chain)

- i.e. expected 3x > 5x or 1x

- (5x) 短衫 : 5toe3-se1 [tɵ52 sɛ3]

- (1x) 暑假 : 1syu3-ka5 [sʮ44 kɑ0]

- i.e. expected 3x > 5x or 1x

- a phrase beginning with a Tone 5 syllable frequently takes on the tone pattern expected of a Tone 1 syllable (a 1x chain)

- i.e. expected 5x > 1x

- (1x) 菜飯 : 1tshe5-ve6 [tsʰɛ44 vɛ0]

- i.e. expected 5x > 1x

- a phrase beginning with a Tone 6 syllable frequently takes on the tone pattern expected of a Tone 2 syllable (a 2x chain)

- i.e. expected 6x > 2x

- (2x) 大菜 : 2da6-tshe5, 2dou6-tshe5 [dɑ22 tsʰɛ33 ~ dəu22 tsʰɛ33]

- i.e. expected 6x > 2x

- less frequently, the above shifts can happen in reverse

- i.e. expected 5x > 3x

- i.e. expected 2x > 6x

- syllables following Tone 7 can also shift chains[11]

- Tone 7 + Tone 5/6 > (Tone 7 + Tone 1/2) > 7.2

- Tone 7 + Tone 6 > 7.3

- most non-checked syllables following Tone 8 collapse into a falling tone, equivalent to a 8.3 chain

- Tone 8 + {Tone 1, 2, 3, 5, 6} > 8.3

Functionally, a Tone 3 pattern (3x chain) is the least common to occur and mostly surfaces when the initial syllable is a numeral phrase (几时; 機時 3ci-zyu6 [tɕi⁵² zʮ¹]) or reduplicated verb (写写; 寫寫 3sia-sia3 [siɑ⁵² siɑ¹]). Below is chart with common other tone patterns included:

| Initial syllable's tone | Chains | 2-syllable[12] | 3-syllable[13] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 陰平 44 | 1x | sin syu 新书 |

sy tsy lin 狮子林 |

| 陽平 223 | 2x | zie syu 泉水 |

waon thie gnioe 黃天源 |

| 6x | don zin 同情 |

don zy men 同志们 | |

| 上聲 52 | 5x | tshau tsy 草纸 |

tan hou ci 打火机 |

| 3x | cieu ngeq 九月 |

||

| 1x | khou nen 可能 |

||

| 陰去 523 | 1x | syu ka 世界 |

|

| 5x | ho kon 化工 |

ia faon ciun 解放军 | |

| 3x | phiau lian 漂亮 |

||

| 陽去 231 | 2x | zy ka 自家 |

dou khue deu 大块头 |

| 6x | gheu gnie 后年 |

ng seq se 五十岁 | |

| 1x | lau sy 老师 |

| Initial Syllable | Chain | 阴平 44 | 阳平 223 | 阴上 52 | 阴去 523 | 阳上去 231 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7x | 7.2 | tshaeq tsho 塌车 |

tsiq deu 节头 |

piq kou 不过 |

feq de 弗但 | |

| 7.3 | poq pau ve 八宝饭 |

|||||

| 7.5 | taeq taon 搭档 |

|||||

| 8x | 8.3 | gnioq te 褥单 |

ngoq jiau 乐桥 |

beq thi 鼻涕 |

gniq li 日里 |

Tone reduction

[edit]Wang (p. 50) additionally identifies a pattern where in certain constructions Tone 5 (/523/) followed by another syllable simplifies to [52] while the second syllable retains its full tone. This can be analyzed comparably to Shanghainese right-prominent sandhi that prioritizes the second syllable and reduces preceding syllables. This right-prominent sandhi pattern occurs commonly in Verb + Object compounds.

- 做人 tsəu523-52 ɲin223

In addition to the above simplification of Tone 5 /523/ to [52], Li (p. 216) additionally describes Tone 2 /223/ and Tone 6 /231/ similarly simplifying to [23 ˨˧] in similar Verb + Object, as well as Adverb + Adjective structures

- 穷大 dʑioŋ223-23 dou231

- 是鬼 zɿ231-23 tɕy52

- 过桥 kou523-52 dʑiæ223

Identified by Bu (2025)[14] describing Suzhou pingtan (but also applicable to Suzhou dialect normally), such tonal reduction generally occurs particularly for Tone 2 and Tone 6 syllables even when not in sandhi chains, and can further reduce to a simple mid/low tone. Because it can occur outside of Verb + Object or Adverb + Adjective syntactic conditions, Bu considers this tonal reduction to simply be a reduction of non-final syllables motivated by those tones (Tone 5 /523/, Tone 2 /223/, Tone 6 /231/) underlyingly being longer and having more tonal targets.

我

6ngou

/ŋəu˨˧˩

[ŋəuᵝ˨˧

1sg

是

6zy

zz̩˨˧˩

zz̩˨˧~zz̩˨

COP

蘇 州 人

1sou-tseu1-gnin2

səu˥ tsøʏ˥ ɲ̟iɲ˨˧/

səuᵝ˥ tsʏ˥ ɲ̟iɲ˩]

Suzhou person

"I am a Soutseu native"

There can be additional variation in how reduced the tones can become based on how casual the sentence is spoken by the speaker.

搿麽

8geq meq

ɡəʔ˨ məʔ˦

ɡəʔ˨ məʔ˧

倷

6ne

ne˨˧

ne˨˧

吃仔

7chiq-3tsy

tɕiəʔ˦ tsz̩˥˩

tɕiəʔ˦ tsz̩˥

飯

6ve

vɛ˨˧

vɛ˨˧

勒

leq

ləʔ˨

ləʔ˨

再

5tse

tse˥˩

tse˥

去吧

5chi ba

tɕiʑ˥˩ bɑ˨˧

tɕiʑ˥˩ bɑ˨˧

"So, maybe you eat your meal first and then go."

In the above sentence, the falling tone [˥˩] on 仔 tsy and 再 tse is reduced to a high-flat [˥] in casual speech, in addition to the Tone 6 /231 ˨˧˩/ (倷 ne, 飯 ve) and Tone 5 /523 ˥˩˧/ (再 tse, 去 chi) words already reducing to [23 ˨˧] and [52 ˥˩] even in slower speech.

Suzhou dialect in literature

[edit]Ballad-narratives

A "ballad–narrative" (說唱詞話) known as "The story of Xue Rengui crossing the sea and Pacifying Liao" (薛仁貴跨海征遼故事), which is about the Tang dynasty hero Xue Rengui[15] is believed to have been written in the Suzhou dialect.[16]

Novels

Han Bangqing wrote The Sing-song Girls of Shanghai, one of the earliest novels in Wu dialect, in Suzhou dialect. Suzhou serves as an important drive for Han to write the novel. Suzhou dialect is used in innovative methods to demonstrate urban space and time, as well as the interrupted narrative aesthetics, making it an integral part of an effort, which is presented as a fundamental and self-conscious new thing.[17] Han's novel also inspired other authors to write in Wu dialect.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ 叶, 祥苓 (1988). 蘇州方言詞典. 江苏教育出版社. p. 407.

- ^ 叶, 祥苓 (1993). 苏州方言志. 江苏教育出版社. p. 454.

- ^ Yue, Anne O. (2003). "Chinese Dialects: Grammar". In Thurgood, Graham; LaPolla, Randy J. (eds.). The Sino-Tibetan Languages (illustrated ed.). London: Routledge. p. 86. ISBN 0-7007-1129-5.

- ^ Chen, Yujie (2015), Chappell, Hilary M (ed.), "The semantic differentiation of demonstratives in Sinitic languages", Diversity in Sinitic Languages, Oxford: Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198723790.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-872379-0, retrieved 2021-12-06

- ^ Clements, Clancy (2000). "Review of Creole and Dialect Continua". Language. 76 (1): 160. doi:10.1353/lan.2000.0054. JSTOR 417399. S2CID 141755433.

She also examines a stylized variety of Suzhou Wu as used to tell stories by native speakers of another dialect.

- ^ Ling, Feng (2009). A Phonetic Study of the Vowel System in Suzhou Chinese (PhD thesis). City University of Hong Kong.

- ^ 叶, 祥苓 (1993). 苏州方言志. 江苏教育出版社. p. 3.

- ^ Wang, Ping (汪平) (2011). 苏州方言研究. pp. 28–29.

- ^ Li, Xiaofan (李小凡) (1998). 苏州方言语法研究. pp. 217, 222.

- ^ Ye, Xiangling (叶祥苓) (1988). 苏州方言志. 江苏教育出版社. p. 118.

- ^ Bu, Tianrang (2025). Phonologies and Language Use in Bindae 評彈, A Genre of Traditional Chinese Music and Storytelling (PhD thesis). University of Chicago. p. 142.

- ^ "【苏白学堂/教程】苏州话连读变调第二课-二字变调".

- ^ "【苏白学堂/教程】苏州话连读变调第三课,多字变调".

- ^ Bu, Tianrang (2025). Phonologies and Language Use in Bindae 評彈, A Genre of Traditional Chinese Music and Storytelling (PhD thesis). University of Chicago. pp. 152–155.

- ^ Idema, Wilt L. (2007). "Fighting in Korea: Two Early Narratives of the Story of Xue Rengui". In Breuker, Remco E. (ed.). Korea in the Middle: Korean Studies and Area Studies: Essays in Honour of Boudewijn Walraven (illustrated ed.). Leiden: CNWS Publications. p. 341. ISBN 978-90-5789-153-3.

A prosimetrical rendition, entitled Xue Rengui kuahai zheng Liao gushi 薛仁貴跨海征遼故事 (The story of Xue Rengui crossing the sea and Pacifying Liao), which shares its opening prose paragraph with the Xue Rengui zheng Liao shilüe, is preserved in a printing of 1471; it is one of the shuochang cihua 說唱詞話 (ballad-narratives

- ^ Idema, Wilt L. (2007). "Fighting in Korea: Two Early Narratives of the Story of Xue Rengui". In Breuker, Remco E. (ed.). Korea in the Middle: Korean Studies and Area Studies: Essays in Honour of Boudewijn Walraven (illustrated ed.). Leiden: CNWS Publications. p. 342. ISBN 978-90-5789-153-3.

for telling and singing) which were discovered in the suburbs of Shanghai in 1967. While these shuochang cihua had been printed in modern-day Beijing, their language suggests that they had been composed in the Wu Chinese area of Suzhou and surroundings,

- ^ Des Forges, Alexander (2007). Mediasphere Shanghai: The Aesthetics of Cultural Production. University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-3081-6. JSTOR j.ctt13x1jm2.