Titian

Titian | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Tiziano Vecellio c. 1488/90 |

| Died | 27 August 1576 (aged 87–88) Venice, Republic of Venice |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Occupation | Artist |

| Movement | Venetian school |

| Signature | |

| Part of a series on the |

| Counter-Reformation |

|---|

|

| Catholic Reformation and Revival |

Tiziano Vecellio (Italian: [titˈtsjaːno veˈtʃɛlljo]; c. 1477/88/90[a] – 27 August 1576),[1] Latinized as Titianus, hence known in English as Titian (/ˈtɪʃən/ ⓘ TISH-ən), was an Italian Renaissance painter,[b] the most important artist of Renaissance Venetian painting. He was born in Pieve di Cadore, near Belluno.[3]

Titian was one of the most versatile of Italian painters, equally adept with portraits, landscape backgrounds, and mythological and religious subjects. His painting methods, particularly in the application and use of colour, exerted a profound influence not only on painters of the late Italian Renaissance, but on future generations of Western artists.[4]

His career was successful from the start, and he became sought after by patrons, initially from Venice and its possessions, then joined by the north Italian princes, and finally the Habsburgs and the papacy. Along with Giorgione, he is considered a founder of the Venetian school of Italian Renaissance painting. In 1590, the painter and art theorist Giovanni Paolo Lomazzo described Titian as "the sun amidst small stars not only among the Italians but all the painters of the world".[5]

During his long life, Titian's artistic manner changed drastically,[c] but he retained a lifelong interest in colour. Although his mature works may not contain the vivid, luminous tints of his early pieces, they are remarkable and original in their loose brushwork and subtlety of tone.

Biography

[edit]Early years

[edit]

The exact time or date of Titian's birth is uncertain. When he was an old man he claimed in a letter to Philip II of Spain to have been born in 1474, but this seems most unlikely.[6] Other writers contemporary to his old age give figures that would equate to birth dates between 1473 and after 1482. Most modern scholars believe a date between 1488 and 1490 is more likely,[7] though his age at death being 99 had been accepted into the 20th century.[8]

He was the son of Gregorio Vecellio and his wife Lucia, of whom little is known. The Vecellio family was well-established in the area, which was ruled by Venice. Titian's grandfather Conte Vecellio was a prominent notary who held a number of offices in the local administration. Three of Conte's sons were notaries, not including Gregorio,[9] who was active as a soldier and closely associated with the Venetian Arsenal,[10] but worked mainly as a timber merchant and also managed mines in the mountainous Cadore region for their owners.[11]

Ludovico Dolce, who knew Titian, says that Titian had four masters, the first being Sebastiano Zuccato, the second Gentile Bellini, then his brother Giovanni Bellini, and last, Giorgione. No documentation for these relationships has been found. The Zucatti family of artists are best known as mosaicists, but there is no evidence that the painter Sebastiano Zuccato himself was active as a mosaicist, although Joannides says he probably was.[12]

According to Giorgio Vasari, who also knew Titian and included a not always accurrate biography of the artist in his Lives, Titian first studied under Giovanni Bellini. Dolce writes that the boy was sent to Venice at age nine, along with his brother Francesco, to live with an uncle and apprentice to Sebastiano Zuccato. Leaving Zuccato, Titian briefly transferred to the studio of Gentile Bellini, one of the largest and most productive workshops in Venice. Following Gentile's death in 1507 he entered into an apprenticeship with Gentile's younger brother Giovanni, acknowledged by contemporaries as the preeminent Venetian painter of the day. As there is no documentation of Titian's work before 1510, there is no way to know which version, Dolce's or Vasari's, is closer to the truth.[13] Living in the city, Titian found a group of young men about his own age, among them Giovanni Palma da Serinalta, Lorenzo Lotto, Sebastiano Luciani, and Giorgio da Castelfranco, nicknamed Giorgione.[14] Francesco Vecellio, Titian's brother, while more workmanlike in his approach to painting and lacking Titian's talent, was able to achieve some notice in his home town of Cadore and the Bellunese area around it.[15]

Giorgio Martinioni mentions in his edition (1663) of Sansovino's guide to Venice a fresco of Hercules painted by Titian above the entrance to the Morosini house, a painting that would have been one of his earliest works, although a year later Marco Boschini rejected this attribution.[16] Others attributed to his early years were the Bellini-esque so-called Gypsy Madonna in Vienna,[17] and The Visitation from the monastery of Sant'Andrea,[18] now in the Accademia, Venice.[d] According to Joannides, features of the Visitation's execution such as the painter's deployment of light to stress the two pregnant women and the focus on colouristic values are qualities to be found in the earliest of Titian's works, and its attribution to him is supported as well by its dramatic expression of movement and the geometry of the arrangement of visual elements on the canvas.[20]

A Man with a Quilted Sleeve is an early portrait, painted around 1509 and described by Giorgio Vasari in 1568. Scholars long believed it depicted Ludovico Ariosto, but now think it is of Gerolamo Barbarigo.[21] Rembrandt had seen A Man with a Quilted Sleeve at auction, and drew a thumbnail sketch of it. Later he was able to examine the painting more closely in the home of the Sicilian merchant Ruffio, who had bought it. The work inspired the Dutch artist to sketch his own self-portrait in 1639 and then to make a similar etching, followed by a self-portrait in oils in 1640.[22]

In 1507–1508, Giorgione was commissioned by the state to create exterior frescoes on the recently rebuilt Fondaco dei Tedeschi, a warehouse for the German merchants in the city,[23] which stood next to the Rialto bridge facing the Grand Canal.[24] Titian and Morto da Feltre worked alongside him. Giorgione painted the facade facing the canal in 1508, while Titian painted the facade above the street, probably in 1509. Many contemporary critics found Titian's work more impressive.[25] Only some badly damaged fragments of the paintings remain.[26] Some of their work is known, in part, through the engravings of Fontana.

The relationship between the two young artists evidently contained a significant element of rivalry. Distinguishing between their works during this period remains a subject of scholarly controversy. A substantial number of attributions have moved from Giorgione to Titian in the 20th century, with little traffic the other way. One of the earliest known Titian works, Christ Carrying the Cross in the Scuola Grande di San Rocco, was long regarded as being by Giorgione.[27]

After Giorgione's early death in 1510, Titian continued to paint Giorgionesque subjects for some time, though his style developed its own features, including the bold and expressive brushwork so characteristic of his later years.[28]

Titian's talent in fresco is shown in those he painted in 1511 at Padua in the Carmelite church and in the Scuola del Santo, some of which have been preserved, among them the Meeting at the Golden Gate, and three scenes (Miracoli di sant'Antonio) from the life of St. Anthony of Padua, Murder of a Young Woman by Her Husband, which depicts The Miracle of the Jealous Husband,[29] A Child Testifying to Its Mother's Innocence, and The Saint Healing the Young Man with a Broken Limb. The Resurrected Christ (Uffizi) also dates to 1511-1512.

On 31 May 1513 Titian petitioned the Council of Ten for a commission to paint a canvas depicting a great battle scene for the Doge's palace (completed only in 1538).[30] At the same time he requested the next available sansaria (or senseria), a broker's patent at the Fondaco dei Tedeschi which assured the recipient an annual stipend of 120 ducats,[31] and whose symbolic value was usually greater than the income itself. The Council, who already knew his reputation, were receptive to his offer. The request was granted, but it was reversed in March 1514. His application was recorded again in November 1514, with the understanding that he had an expectation of Giovanni Bellini's position unless another became vacant in the meantime. Titian did not obtain the sansaria upon Bellini's death in late 1516, however.[32] Apparently the Senate wanted to keep his services in reserve until he proved himself, and the appointment was withheld until 1523.[33]

The sansaria was important for Titian with its implicit recognition as quasi-official painter to the republic and represented an opportunity to gain major commissions from the state. Once he obtained it, he transformed it over time into a sinecure which required little work, although it was intended as payment for the performance of certain tasks in the Doge's Palace.[34]

Growth

[edit]During this period (1516–1530), which may be called the period of his mastery and maturity, the artist moved on from his early Giorgionesque style, undertook larger, more complex subjects, and for the first time attempted a monumental style. Giorgione died in 1510 and Giovanni Bellini in 1516, while Sebastiano del Piombo had gone to Rome, leaving Titian unrivaled in the Venetian School.[35] For sixty years he was the undisputed master of Venetian painting.[36]

In 1516, he completed his masterpiece, the Assumption of the Virgin, for the high altar of the Basilica di Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari. It is still in situ, and is his largest single panel.[12] This piece of colourism, executed on a grand scale rarely before seen in Italy, created a sensation.[37] In the pictorial structure of the Assumption, the three domains of the composition are occupied by the apostles on earth, the Madonna rising in the sky, and God the Father in heaven looking over all, united to form a coherent whole, unlike the less dynamic and more fragmented renditions of earlier painters. According to Bruce Cole, Titian studied traditional renderings of the Assumption like every artist of the Renaissance. He would have been familiar with Andrea Mantegna's large fresco of the subject executed in Padua's church of the Eremitani in the 1450s, having worked in 1510 on frescoes for the Scuola del Santo in Padua. Nearby Venice on the lagoon isle of Murano there was another example of the subject, painted by Giovanni Bellini and his workshop, that Titian would have known. Although he surely held these previous works in high esteem, his approach to composing his own Assunta was individualistic and innovative.[38] [39]

The commission for the Assumption, undertaken in 1515, was soon followed by commissions for major altarpieces at Brescia and Ancona, as well as for the altar of the Pesaro family chapel in the Frari. By 1520 he must have been working on several of these works at once, including the second version of the San Nicolò altarpiece[40] now displayed in the Vatican Pinacoteca.[12]

Merchants in the Dalmatian city of Ragusa (Dubrovnik), across the Adriatic Sea from Italy, commissioned a polyptych The Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary by Titian and his workshop, now on the high altar of the cathedral in Ragusa, as well as a recently restored painting by Titian depicting St Blaise, Mary Magdalene, the Archangel Raphael and Tobias in the Dubrovnik Dominican convent.[41][42]

St Sebastian, painted on a separate panel of a polyptych, was commissioned by a papal legate to Venice, Altobello Averoldi, for the altarpiece of the Church of Santi Nazzaro e Celso in Brescia.[43] Bette Talvacchia alludes to Luba Freedman's discussion of the figure of Sebastian in terms of its reception by a contemporary "learned audience", acquainted with the literature of art, who could be said to have had some claim to connoiseurship.[44] Signed and dated 1522, according to David Rosand it was ready for viewing in 1520. Jacopo Tebaldi, an agent for Alfonso I d'Este, was present for the studio preview, and schemed to purchase it for the duke. Saint Sebastian, bound and wounded, had special status as an intercessor during periodic outbreaks of the plague, and was a very popular subject of sacred painting. Such a figure, intended for a religious context, nonetheless provided an occasion for portrayal of the male nude and could be appreciated as an independent work of art.[45]

To this period belongs a more extraordinary work, The Assassination of Saint Peter Martyr (1530), formerly in the Dominican Church of San Zanipolo, and destroyed by a fire in 1867.[46][47] Only copies and engravings of this proto-Baroque picture remain. It combined extreme violence and a landscape, mostly consisting of a great tree, that pressed into the scene and seems to accentuate the drama in a way that presages the Baroque.[48]

The artist simultaneously continued a series of small Madonnas, which he placed amid beautiful landscapes, in the manner of genre pictures or poetic pastorals. The Virgin with the Rabbit, in the Louvre, is the finished type of these pictures. Another work of the same period, also in the Louvre, is the Entombment. This was also the period of the three large and famous mythological scenes for the camerino of Alfonso d'Este in Ferrara, The Bacchanal of the Andrians and the Worship of Venus in the Museo del Prado and the Bacchus and Ariadne (1520–23) in London,[49] "perhaps the most brilliant productions of the neo-pagan culture or 'Alexandrianism' of the Renaissance, many times imitated but never surpassed even by Rubens himself."[14] Finally this was the period when Titian composed the half-length figures and busts of young women, such as Flora in the Uffizi and Woman with a Mirror (or Woman at Her Toilet) in the Louvre. There is some evidence that prostitutes were used as models by Titian and other painters of the time,[50] including some of Venice's famous courtesans.[51] In Syson's view, if this practice was generally known in 16th-century Venetian society, it might have influenced the "reactions and interpretations" by some of the paintings' owners and those who viewed them.[50]

Maturity

[edit]

During the next period (1530–1550), Titian developed the style introduced by his dramatic Death of St. Peter Martyr.

Bacchus and Ariadne (1520–1523),[52] depicts Ariadne, a Cretan princess abandoned by Theseus, whose ship is shown in the distance and who has just left her at the Greek island of Naxos, at the moment when Bacchus arrives. Bacchus, falling immediately in love with Ariadne, leaps from his chariot, drawn by two cheetahs, to be near her. In the mythical love story, Ariadne is frightened by the wine god's raucous retinue and runs away. Bacchus wins her over and they are married, following which he creates from her jewelled wedding crown the constellation of the Corona Borealis, whose stars Titian places in the upper left of the sky to symbolize their eternal love.[53] The painting belongs to a series commissioned from Bellini, Titian, and Dosso Dossi, for the Camerino d'Alabastro (Alabaster Room) in the Ducal Palace, Ferrara, by Alfonso I d'Este, Duke of Ferrara, who in 1510 tried to commission Michelangelo and Raphael for the series.[54]

In early 1508, Titian's father Gregorio had fought with the victorious forces of Bartolomeo d'Alviano at Valle against the armies of Maximilian I.[55] In 1513, Titian applied to the Council of Ten of the Republic of Venice, offering to paint a battle scene in the Sala del Consiglio Maggiore (Hall of the Great Council) of the Ducal Palace. The battle painting, which came to be known as Battle of Cadore, was commissioned in 1513 and documents in the palace archives record that Titian went to work on it immediately, but eventually his enthusiasm for the project diminished and by June 1537, it remained unfinished. A document dated 23 June 1537 records that he had been granted a broker's patent in 1513, contingent on his painting the canvas of the battle scene, and since 5 December 1516 he had been paid the revenues of that appointment. Because he had not fulfilled its terms the council demanded he return all the funds he had received for those years in which he had done no work.[30]

When Titian was threatened with withdrawal of the commission and the obligation to refund the payments he had received, a serious competitor, Pordenone, was available to replace him, one who had proved his abilities in the specialized field of painting battle scenes filled with horses and horsemen.[30] Since at least 1520 Pordenone had mounted a powerful challenge to the primacy of Titian in Venice.[56] According to Harold Wethey, the oil-on-canvas painting finally completed by Titian in 1538 covered the deteriorated fresco, Battlle of Spoleto, executed by Guariento di Arpo in the 14th century.[57] Contemporary or near contemporary sources pertaining to the canvas are contradictory and do not clarify exactly when it was painted or which particular battle it represented. Sansovino says Titian omitted the inscription placed above the former painting by Guariento of the battle of Spoleto.[30]

This major battle scene by Titian was lost—with many other major works by Venetian artists—in the 1577 fire that destroyed all the old pictures in the great chambers of the Doge's Palace (Palazzo Ducale). It depicted in life-size the moment when the Venetian general d'Alviano attacked the enemy, with horses and men crashing down into a river during a heavy rainstorm (according to Vasari).[30] It was Titian's most important attempt at a tumultuous and heroic scene of movement to rival Raphael's The Battle of Constantine at the Milvian Bridge, Michelangelo's equally ill-fated Battle of Cascina, and Leonardo da Vinci's The Battle of Anghiari (these last two unfinished). Gillet mentions a "poor, incomplete copy at the Uffizi, and a mediocre engraving by Fontana."[14] This period of Titian's work is still represented by the Presentation of the Blessed Virgin (Venice, 1539), one of his most popular canvasses, and by the Ecce Homo (Vienna, 1543). Despite its loss, the Battle of Cadore had a great influence on Bolognese art and Rubens. His Speech of the Marquis del Vasto (Madrid, 1541) was also partly destroyed by fire.[14]

Esthy Kravitz-Lurie writes that modern scholarly consensus is that the traditional identification of Alfonso d'Avalos, Marquis of Vasto, as the male protagonist in Titian's painting, Allegory of Marriage, now in the Louvre, presents problems of interpretation.[58] It is generally believed to have been finished in 1530–1535. Alfonso d'Avalos wrote a letter in November 1531 to Pietro Aretino, in which he stated that he wished to be portrayed by Titian with his wife and son. Although the letter does not prove that the artist undertook such a commission, the painting subsequently was regarded as a portrait of the military figure. The earliest identification of the painting's protagonist as the warrior d'Avalos is in an inventory of artworks belonging to the English King Charles I, completed in 1639 by Abraham van der Doort, Keeper of Charles I's art collections. As noted by Paul Johannides, van der Doort's reference can be interpreted as 'owned by' rather than as 'representing', suggesting that Alfonso might have been the commissioner of the painting rather than its male subject.[59]

Walter Friedlaender calls Titian's three paintings on the ceiling of Santa Maria della Salute "manifestations of genius unprecedented even in Titian's own work", as expressed in the impassioned power of movement in the composition and in his "daring" use of contrapposti and foreshortening. These represent Cain and Abel, the Sacrifice of Isaac, and David and Goliath. Friedlaender says these paintings, finished in 1544, were greatly influential in the development of Baroque painting, and admired because of his success in projecting powerful movement in the spaces overhead without using a complicated system of perspective. Further, this new mode introduced in the Salute paintings was an important influence on Veronese's decorations in San Sebastiano and on Rubens in his later decorations for the Church of San Carlo Borromeo[60] in Antwerp.[61] At this time also, during his visit to Rome, the artist began a series of reclining Venuses: The Venus of Urbino of the Uffizi, Venus and Love at the same museum, Venus—and the Organ-Player, Madrid, which shows the influence of contact with ancient sculpture. Giorgione had already dealt with the subject in his Dresden picture, finished by Titian.[14]

Lisa Jardine says a competitive acquisitiveness was necessary for the increased production of extravagantly expensive works of art during the Renaissance. A painter who wanted to establish his reputation was obliged to stimulate a commercial demand for his art, rather than to build it on some imagined basis of intellectual value. Titian's canvases of voluptuous naked women reclining in seductive poses were regarded as learned "visual explorations of allegories drawn from classical Latin literature" by art historians of the 19th-century. More recent scholarship has revealed contemporary correspondence indicating these works of art were created to satisfy a strong demand for erotically charged paintings of nudes in blatantly sexual poses, and meant to be hung in the bedrooms of the nobilty. When in 1542 Cardinal Alessandro Farnese saw the painting now known as The Venus of Urbino at the duke's summer palace, he made haste to commission from Titian a similar nude for himself,[62] the first in a series representing Danaë and the golden shower.[63]

The Farnese Danaë (1544–1546) is a masterful demonstration of Titian's painterly use of colour, imbuing the painting, according to Janson, with "unrivaled richness and complexity of colour". Janson contrasts Titian's embrace of the sensual and emotional appeal of colore with Michelangelo's more intellectual emphasis on disegno, or design, as seen in the detailed drawings of figures made in preparation for his painted compositions.[64] Danaë was one of several mythological paintings, or "poesie" ("poems"), as the painter called them.[65] This painting was done for Cardinal Farnese,[66] but a later variant was produced for Philip II[65] (while he was still crown prince),[67] for whom Titian painted many of his most important mythological paintings. Although Michelangelo adjudged this piece deficient from his point of view regarding the importance of preliminary drawings for a composition,[64] Titian and his studio produced several versions for other patrons.

From the beginning of his career, Titian was a virtuoso portrait-painter, demonstrated in works such as La Bella (Eleanora de Gonzaga, Duchess of Urbino, at the Palazzo Pitti). He painted the likenesses of princes, or Doges, cardinals or monks, and artists or writers. "...no other painter was so successful in extracting from each physiognomy so many traits at once characteristic and beautiful".[14] Concerning portraiture and portrait-painters, the art historian Kenneth Clark writes: "The portrait is a thorn in the side of the student of aesthetics. Having established to his satisfaction that art does not consist in imitation, he must face the fact that three of the greatest artists who ever lived, Titian, Rembrandt, and Velázquez, gave the best of their talents to painting portraits."[68]

These qualities show in the Portrait of Pope Paul III, the Portrait of Pietro Aretino, the Portrait of Isabella of Portugal, and the series of Emperor Charles V, especially the Equestrian Portrait of Charles V (1548), commissioned by the emperor to commemorate his defeat of the Schmalkaldic League at the Battle of Mühlberg.[69] It shows Charles in his battle armour carrying a lance, suggesting the appurtenances of a Roman emperor going on campaign. According to Thomas DaCosta Kaufmann, depicting Charles in contemporary armour with a lance also suggests that in the context of Mühlberg, Charles is appearing in his role as a Christian knight.[70] In 1533, after painting a portrait of the Emperor Charles V in Bologna, Titian was made a Count Palatine and Knight of the Golden Spur.[71] According to Crowe and Cavalcaselle, his children were also made nobles of the Empire.[72]

His appointment as court painter to Charles V allowed Titian to gain royal patronage and work on prestigious commissions. Considering the profoundly conservative disposition of Venetian society and politics, painters in Titian's time were relegated to the craftsmen guild of the Arte dei Depentori.[73] Although active in the local affairs of the guild,[74] Titian was far from feeling confined by the medieval corporate system of the guilds with their duties and political strictures, and enjoyed the freedom afforded by his continued residence in the Most Serene Republic. Having been court painter of Charles V since 1533, he also took commissions from the pope, and executed works for the courts of Ferrara, Mantua, and Urbino. The duties imposed on him by the imperial court in exchange for his annual pensions were comparatively light. He crossed the Alps twice to join the emperor in Germany and made a few trips to Asti, Bologna, and Milan, but otherwise his presence at court was not required, allowing him to avoid the degrading obligations of most courtiers.[75]

In the first decades of the 16th century, sophisticated patrons of art such as Isabella d'Este had begun to seek works for their collections beyond the conventional portraits, civic images, and altarpieces, and to acquire paintings by certain artists, whose productions were avidly sought by collectors. Consequently, extraordinarily talented artists including Raphael, Michelangelo, and Titian rose in social status far above that traditionally accorded painters, who previously had been regarded as tradesmen, and acquired wealth of their own.[76] As recounted by Sophie Bostock, Titian was appointed "First Painter to the Most Serene Republic of Venice" upon the death of Giovanni Bellini, and his fame throughout Europe increased accordingly. Titian, like Gentile Bellini, was one of the first artists to be granted noble status by a monarch—only the work and person of Michelangelo were held in such high esteem. In a self-portrait from the 1550s, he depicts himself clothed in the rich attire of a patrician, including the heavy gold chain bestowed on him by Charles V in 1533.[77] In 1540 he received a pension of 50 ducats from d'Avalos, marquis del Vasto.[78]

Art historian Carlo Corsato conducted research to reconstruct the sequence of events concerning Titian's pensions, and the context in which they occurred: On 15 August 1541, Charles V awarded Titian an annual stipend of 100 scudi payable at a bank in Milan. Early in 1548, Charles and Titian met at the Diet of Augsburg. During his sojourn there, Titian solidified his position as official court painter by completing six paintings, among them the Equestrian Portrait of Charles V. The meeting also afforded Titian a chance to make the emperor aware that he had not received a single payment of the stipend. On 10th July 1548 Charles V granted him a second annual pension of 100 scudi, in addition to the stipend granted in 1541. Philip II signed a royal deed on 5 July 1571 reaffirming his father's earlier concession of a stipend of 200 scudi annually to Titian. He also bestowed on the artist the right to transfer the privilege to his son Orazio following his death.[79]

Titian was adept in managing his affairs and in lending his money at interest—another source of some profit was a contract obtained in 1542 for supplying grain to Cadore when local stores were low.[80] Titian had a villa on the Manza Hill in front of the church (Chiesa dei Santi Pietro e Paolo) of Castello Roganzuolo, where he painted a triptych.[81] The so-called Titian's mill, frequently discernible in his studies, is at Collontola, near Belluno.

Titian visited Rome in 1545–1546 and was honoured with the freedom of the city.[82] He was offered the office of piombotore or keeper of the papal seal three times, the first when he became the Farneses' chosen portraitist,[83] and presumably the last time when Sebastiano del Piombo's death left the position unoccupied, but he politely refused the lucrative sinecure.[84] He was summoned to Augsburg from Venice in 1547 to paint portraits of Charles V and of other dignitaries. Titian took advantage of the opportunity to present himself as more than a portrait painter and one whose versatility as an artist could be of value to the emperor.[69]

Final years

[edit]

After his first trip to the imperial court at Augsburg, Titian's production gained new dimensions as a result of his presence there and the relationship, built on mutual trust, that he established with Charles V. Commissions from the emperor and then from his son Philip II monopolized the artist's output from the 1550s. The model of portraiture he developed for the Habsburgs became a standard for princes, nobles, and ecclesiastics in the hierarchy of power, and thus necessitated a reordering of his workshop to accommodate increased demand from a wider clientele.[85]

Consequently he began to produce variants and replicas of his works in a systematic almost assembly-line fashion, an unprecedented practice.[86][87] In his studio Titian used "specialised collaborators" who made copies of his works, which he then retouched for corrections and to impart his esprit to paintings that might be sold as originals, or to purchasers who were not necessarily averse to settling for copies. In Titian's time retouching was practiced widely by artists, especially to perfect the work done by apprentices in their workshops.[86]

Titian relentlessly revised his works, but the changes he made did not follow a linear progression. He tested the positions of different motifs such as figures and landscape elements numerous times, but new arrangements were not always adopted and those previously rejected might be taken up again.[88] When laying-in the background of a composition, the master and his workshop team typically laid in more than one iteration, which might be obliterated by others, as often happened, or revised and reworked later, even 40 or 50 years later.[89] Titian treated his underdrawings as mere suggestions, and frequently made changes to the original drawing which might not be followed in the painting's execution.[90]

For Philip II, he painted a series of large mythological paintings known as the "poesie", mostly from Ovid, which scholars regard as among his greatest works.[91] Thanks to the prudishness of Philip's successors, these were later mostly given as gifts, and only two remain in the Prado. Titian was producing religious works for Philip at the same time, some of which—the ones inside Ribeira Palace—are known to have been destroyed during the 1755 Lisbon Earthquake. The "poesie" series contained the following works:

- Danaë, sent to Philip in 1553,[92] now in the Wellington Collection, with earlier and later versions

- Venus and Adonis, of which the earliest surviving version, delivered in 1554, is in the Prado, but several versions exist

- Perseus and Andromeda (Wallace Collection, now damaged)

- Diana and Actaeon, owned jointly by the National Gallery in London and the National Gallery of Scotland in Edinburgh

- Diana and Callisto, were dispatched in 1559, owned jointly by the National Gallery and the National Gallery of Scotland

- The Rape of Europa (Boston, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum), delivered in 1562

- The Death of Actaeon, now in the National Gallery in London, begun in 1559 but worked on for many years and never completed or delivered[93]

In 1623, when Prince Charles of England was to be married to Infanta Maria Anna of Spain, "[h]er enormous dowry was to be partially paid in pictures. Prince Charles had asked for all of Titian's Poesie".[94] When Charles cancelled the wedding, "Titian's Poesie, not yet shipped, were taken out of their crates and hung back up on the walls of the Spanish royal palace".[95]

The poesie, except for The Death of Actaeon, were brought together for the first time in nearly 500 years in an exhibition in 2020 and 2021 that travelled from the National Gallery in London, to the Museo del Prado in Madrid, to the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston, where it closed on January 2, 2022.[96][97][98]

- Titian's poesie series for Philip II

Another painting that apparently remained in his studio at his death, and has been much less well known until recent decades, is the powerful, even "repellent" Flaying of Marsyas (Kroměříž, Czech Republic).[99] Another violent masterpiece is Tarquin and Lucretia (Cambridge, Fitzwilliam Museum).[100]

According to the art historian Louis Gillet:

For each of the problems which he successively undertook he furnished a new and more perfect formula. He never again equalled the emotion and tragedy of the "Crowning with Thorns" (Louvre), in the expression of the mysterious and the divine he never equalled the poetry of the "Pilgrims of Emmaus", while in superb and heroic brilliancy he never again executed anything more grand than "The Doge Grimani adoring Faith" (Venice, Doge's Palace), or the "Trinity", of Madrid. On the other hand from the standpoint of flesh tints, his most moving pictures are those of his old age, the "Dana" of Naples and of Madrid, the "Antiope" of the Louvre, the "Rape of Europa" (Boston, Gardner collection), etc. He even attempted problems of chiaroscuro in fantastic night effects ("Martyrdom of St. Laurence", Church of the Jesuits, Venice; "St. Jerome," Louvre). In the domain of the real he always remained equally strong, sure, and master of himself; his portraits of Philip II (Madrid), those of his daughter, Lavinia, and those of himself are numbered among his masterpieces.[14]

Titian married off his daughter Lavinia in 1555 with a noble dowry of 1,400 ducats[101] to Cornelio Sarcinelli, a member of the local nobility of Serravale, a town on the road between Venice and Pieve di Cadore. Lavinia bore five children whose names are known, two of them daughters, and there is some evidence she had another, older girl. The fact that Cornelio provided a dowry of 1,200 ducats for their daughter Helena gives some idea of his wealth.[102]

Around 1560,[103] Titian painted the oil on canvas Madonna and Child with Saints Luke and Catherine of Alexandria, a derivative on the motif of Madonna and Child. It is suggested that members of Titian's Venice workshop probably painted the curtain and Luke, because of the lower quality of those parts.[104]

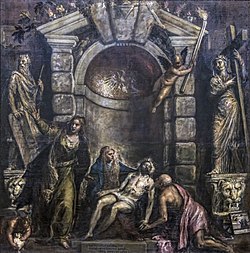

He continued to accept commissions to the end of his life. Like many of his late works, Titian's last painting, the Pietà, is a dramatic, nocturnal scene of suffering. He apparently intended it for his own tomb chapel. He had selected, as his burial place, the chapel of the Crucifix in the Basilica di Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari, the church of the Franciscan Order. In payment for a grave, he offered the Franciscans a picture of the Pietà that represented himself and his son Orazio, with a sibyl, before the Savior. He nearly finished this work, but differences arose regarding it, and he settled on being interred in his native Pieve. Yet he ended up being interred in the Frari.[105]

Death

[edit]

While the plague raged in Venice, Titian died on 27 August 1576.[106] Given the modern scholary consensus that he was born between 1488 and 1490, he would have been at least eighty-six years old, and no more than ninety.[7] Although in 1575 he had installed his last painting, the Pietà, which he designed specifically for his own burial site in the Frari, it was soon removed, and he was buried beneath the Frari's Altar of the Crucifix (Altare del Crocifisso) without the painting in place.[107] According to Nichols, the Franciscan friars of the Frari felt that the painting did not respect the 'ancient devotions' to the medieval crucifix in the Chapel of Christ, and had returned it to him. After his death, it apparently remained in his studio and eventually the painter Jacopo Palma il Giovane, a pupil in his workshop, acquired it and added a few small touches. After Palma's death in 1628, the church of Sant'Angelo acquired the canvas in 1631, where it remained until the church was destroyed in the early 18th century. The Pietà became part of the collection of the Accademia Galleries in 1814.[108] Very shortly after Titian's death, his son, assistant and sole heir Orazio, also died of the plague, greatly complicating the settlement of his estate, as he had made no will.[109]

A large monument to honor Titian at his original burial site was commissioned by the Emperor Ferdinand I of Austria in 1839. Its completion was carried on after his abdication in 1848 by his successor Franz Joseph through 1852.[110] Luigi Zandomeneghi, a student of Antonio Canova, and director of the Accademia when the commission was made in 1843, was selected to create the monument. It was built of the finest Carrara marble across the nave from his own Ca' Pesaro Madonna. His sons, Pietro and Andrea, completed the project after he died.[107]

Family and workshop

[edit]

National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh.

Titian's wife, Cecilia, was a barber's daughter from his hometown of Pieve di Cadore. As a young woman she had been his housekeeper and mistress for some five years. Cecilia had already borne Titian two sons, Pomponio and Orazio,[111] when in 1525 she fell seriously ill. Titian, wishing to legitimize the children, married her. Cecilia recovered, the marriage was a happy one, and they had another daughter who died in infancy.[112] In August 1530 Cecilia died.[113] Titian remarried, but little information is known about his second wife; she was possibly the mother of his daughter Lavinia.[114] Titian had a fourth child, Emilia, the result of an affair, possibly with a housekeeper.[115] His favourite child was Orazio, who became his assistant.

In 1531, Titian moved his two sons and infant daughter to a new house on the northern edge of Venice in Biri Grande. The casa da stazio had two floors, the lower probably used for storage, and the upper as his dwelling place. His workshop, built of masonry and wood, was separated from the rest of the house. The grounds featured a private garden where he could air-dry his paintings and hide them from observation. The house had direct access to the lagoon, allowing the paintings to be shipped easily to patrons.[116] His sister Orsa came from Pieve di Cadore to help manage the household and his business affairs.[117]

In about 1526 he had become acquainted with Pietro Aretino, the influential and audacious figure who features in the chronicles of the time.[e] Philip Cottrell considers that a crucial element in Titian's success internationally was the endorsement of the satirist Aretino, who arrived in Venice in March 1527, and rarely left the city until he died in 1556. Aretino began friendships with Titian and with the sculptor and architect Jacopo Sansovino, also new arrived from central Italy. The three were so close they were known popularly in Venice as "the triumvirate", and effectively became the centre of the city's artistic establishment, around which revolved a group of lesser artists. Aretino enlisted Titian and Sansovino to join him in pursuing the patronage of Federico II Gonzaga, Marquis of Mantua, and by the autumn of 1527 the Marquis had received a portrait of Aretino, now lost, from Titian's hand. Numerous important commissions and an introduction to the Emperor Charles V followed.[120]

The Italian painter Tintoretto was brought when he was very young to Titian's studio by his father. Tom Nichols says Tintoretto probably entered Titian's workshop during the period of 1530–1539, but only for a very brief time, and that he likely switched to another Venetian studio.[121] Ridolfi tells in his Life of Tintoretto (1642) that after being cast out of Titian's studio, the young Tintoretto realized he could "become a painter by studying the canvases of Titian and the reliefs of Michelangelo Buonarroti". To remind himself of this aspiration he wrote on the walls of his rooms a motto for his striving: "il disegno di Michelangelo e il colorito di Tiziano" ("Michelangelo's design and Titian's colour").[122][123]

Several other members of the Vecelli family tried a hand at painting. Francesco Vecellio, Titian's brother, worked as his assistant in 1511, then gave up painting for a while to become a soldier. Francesco worked for much of his career in Venice, and shared his brother's workshop in Venice until the early 1550s, often working side-by-side with him. Francesco got most of his commissions from the interior regions of Veneto, especially from Belluno and Cadore.[124] Historical documents show that these commissions were carried out at the family workshop.[125] Numerous works executed in Belluno and Cadore are attributed to Francesco, including altarpieces in the Church of Santa Maria Annunziata, Sedico, the Church of Santa Croce, Belluno (now at the Old Masters Staatliche Museum in Berlin), the Church of Madonna della Difesa, San Vito di Cadore, and the Church of Santa Maria Nascente, Pieve di Cadore.[126]

Tom Nichols describes how over time Titian's relatives such as his brother Francesco, and his younger cousins Marco and Cesare played more prominent roles in the Titian workshop at Biri Grande. Titian produced the so-called Allegory of Prudence, in the early 1570s, representing his growing desire for artistic continuity in a family succession. Nichols thinks it likely that Erwin Panofsky is correct in suggesting that the allegory depicting the heads of wolf, lion and dog represents portraits of Titian, Orazio and (possibly) Marco as the three generations of the Vecellio family workshop. This ideal image, however, required manipulation of the geneological and historical facts on Titian's part. Marco (1545–c. 1611), was not, as the image seems to imply, Orazio's son, but instead a distant second cousin who had come to Venice from Cadore about 1560, and probably played an active role in the workshop only in the last decade of Titian's life.[11] He created several productions in the ducal palace, the Meeting of Charles V and Clement VII in 1529; in San Giacomo di Rialto, an Annunciation; in Santi Giovanni e Paolo, Christ Fulminant. A son of Marco, named Tiziano (or Tizianello), painted early in the 17th century. He made a name for himself as a portraitist, but is best known for writing a biography of his relative Titian, published in 1622.[127]

Few of the pupils and assistants of Titian became well known in their own right; for some being his assistant was probably a lifetime career. Paris Bordone and Bonifazio Veronese were his assistants during some points in their careers. Giulio Clovio said Titian employed El Greco (or Dominikos Theotokopoulos) in his last years. Polidoro da Lanciano is said to have been a follower or pupil of Titian. Other followers were Nadalino da Murano,[128] Damiano Mazza,[129] and Gaspare Nervesa.[130]

Process

[edit]Tom Nichols says that the role of colore as the defining aesthetic in Venice, and the related concept that an all-encompassing 'Venetian-ness' determined artistic developments there, is sometimes exaggerated.[131] He finds that Titian's late style drew attention to the manner in which 'colouring' (colorito), rather than mere colour (colore), could shape the composition of a painting.[132] According to David Rosand, there was an aesthetically refined audience in the 16th century, consisting mainly of fellow artists, that was keenly responsive to Titian's art, and responded to the challenge presented by his expressive brushwork. In his discussion of the interpretation of Renaissance brushwork generally, Rosand writes that one point should be emphasized: the semantic distinction between colorito and colore. Colorito is "the act of colouring, the actual application of paint and manipulation of the brush", while Venetians hardly ever used the uninflectional noun colore. For him, the style of Ventian painting, il colorito alla veneziana, characterized by an open pictorial structure with its parts connected in a fabric of constructive brushstrokes, defines itself by its process.[133]

Rosand wrote of the "caressing touch" of Titian's brush—[134] in his essay, "Titian and the Critical Tradition", he says Aretino perceived that a primary fount of Titian's imitative power was the process and structure of his brushwork.[135] Sylvia Ferino-Pagden finds that his brushwork seems sometimes to have been done with a leisurely carelessness, and at other times to have been dashed off with intense energy. Titian's technique of open painting with visible traces of brushwork was revolutionary, and gave his portrayals an unprecedented sensuous effect. His later work influenced his contemporaries and the painters of following centuries up to the modern day, and set a mark to which later artists compared themselves, including even the Expressionists.[134]

Dunkerton, Spring et al, the authors of a study that appeared in a National Gallery technical bulletin, describe the various aspects of the artist's technique as revealed by technical analysis They recount that Joyce Plesters conducted an examination of Bacchus and Ariadne during its cleaning and restoration treatment in 1967–1969, following which Lorenzo Lazzarini made related studies in Venice. Plesters's and Lazzarini's investigations showed that Titian used a traditional gesso ground, occasionally modified by an imprimatura layer, that his paint medium was a drying oil, and that the paint layer composition revealed in cross-sections of paint samples can be complex, either to attain certain colour effects or as a result of the various adjustments and changes he made while applying the paint. Since these tests were carried out many more of Titian's paintings have been analysed using different technical processes and new scientific methods, especially developments in infrared technology, that disprove the long-established belief that Titian composed his works wholly in paint without first drawing his intended design.[136]

Printmaking

[edit]

Titian never attempted engraving, but he was very conscious of the importance of printmaking as a means to expand his reputation. In the period 1515–1520 he designed a number of woodcuts, including an enormous and impressive one of The Drowning of Pharaoh's Army in the Red Sea, in twelve blocks, intended as wall decoration as a substitute for paintings;[137] and collaborated with Domenico Campagnola and others,[138] who produced additional prints based on his paintings and drawings. Much later he provided drawings based on his paintings to Cornelis Cort from the Netherlands who engraved them. Martino Rota followed Cort from about 1558 to 1568.[139]

Painting materials

[edit]Titian employed an extensive array of pigments and it can be said that he availed himself of virtually all available pigments of his time.[140] In addition to the common pigments of the Renaissance period, such as ultramarine, vermilion, lead-tin yellow, ochres, and azurite, he also used the rare pigments realgar and orpiment.[141]

Titian hair

[edit]Titian hair has been used to describe red hair, almost always on women, since the 19th century. Anne Shirley, from Lucy Maud Montgomery's 1908 novel Anne of Green Gables, is described as having Titian hair when 15:

Well, we heard him say—didn't we, Jane?—'Who is that girl on the platform with the splendid Titian hair? She has a face I should like to paint.' There now, Anne. But what does Titian hair mean?" "Being interpreted it means plain red, I guess," laughed Anne. "Titian was a very famous artist who liked to paint red-haired women."

Present day

[edit]

The art historian Peter Humfrey says some three hundred items are catalogued in his book Titian: The Complete Paintings, but that if all the paintings issued from the artist's workshop had been included, that number might have been doubled.[143] According to Joanna Woods-Marsden, Humfrey's list of 300 pictures includes twenty lost works whose appearance was recorded in paintings or print, for a total of 280 surviving works. His catalogue supplants the catalogue raisonne published by Harold Wethey in 1969. She points out that assembling such a catalogue presents complications for the cataloguer, but a list of Titian's corpus, as Humfrey notes, is made more difficult by the fact that Titian relied heavily on workshop assistants, with lesser standards.[144]

Two of Titian's works in private hands were put up for sale in 2008. One of these, Diana and Actaeon, was purchased by the National Gallery in London and the National Galleries of Scotland on 2 February 2009 for £50 million.[145] The galleries had until 31 December 2008 to make the purchase before the work would be offered to private collectors, but the deadline was extended. The sale created controversy with politicians who argued that the money could have been spent more wisely during a deepening recession. The Scottish Government offered £12.5 million and £10 million came from the National Heritage Memorial Fund. The rest of the money came from the National Gallery and from private donations. The other painting, Diana and Callisto, was bought jointly by the National Gallery and National Galleries of Scotland in 2012.[146]

Gallery of works

[edit]-

Portrait of a Lady ('La Schiavona') 1510-12

-

Noli me tangere, 1511–15, National Gallery London

-

Portrait of Jacopo Sannazaro, 1514–18, Royal Collection, UK

-

Man with a glove, c. 1520, Louvre, Paris

-

David and Goliath, 1542–44, Santa Maria della Salute, Venice

-

Saint Jerome in Penitence, c. 1552

-

Altarpiece of James the Greater, 1558, San Lio church, Venice

-

The Entombment, c. 1572, Prado Museum, Madrid

-

The Flaying of Marsyas, 1570s

-

Portrait of Federico II Gonzaga, c. 1529. Museo del Prado, Madrid.

-

Pesaro altarpiece, 1521–26, Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari, Venice

Notes

[edit]- ^ See below; c. 1488/1490 is generally accepted[why?] despite claims in his lifetime that he was older, Getty Union Artist Name List and Metropolitan Museum of Art timeline, retrieved 11 February 2009 both use c. 1488. See discussion of the issue below and at When Was Titian Born?, which sets out the evidence, and supports 1477. Gould (pp. 264–66) also sets out much of the evidence without coming to a conclusion. Charles Hope in Jaffé, 2003 (p. 11) also discusses the issue, favouring a date "in or just before 1490" as opposed to the much earlier dates, as does Penny (p. 201) "probably in 1490 or a little earlier".

- ^ Though the modern Republic of Italy had yet to be established, the Latin equivalent of the term Italian had been in use for natives of the region since antiquity.[2]

- ^ The contours in early works may be described as "crisp and clear", while of his late methods it was said that "he painted more with his fingers than his brushes." Dunkerton, Jill, et al., Dürer to Veronese: Sixteenth-Century Painting in the National Gallery, pp. 281–286. Yale University, National Gallery Publications, 1999. ISBN 0-300-07220-1

- ^ The website of Accademia attributes this work to Sebastiano del Piombo, while noting alternative attributions to "Giorgione and Titian in his early period",[19] and the Italian General Catalogue of Cultural Property mentions Titian and Sebastiano del Piombo, simply attributing the work to the Venetian school.[18]

- ^ "The relationship between the writer and the painter became particularly close over the almost thirty years Aretino spent in Venice."[118] Aretino became "the closest companion of Titian's life, his most sensitive critic, as well as his adviser, agent, publicist, debt collector, scribe, and hanger-on."[119]

References

[edit]- ^ "Titian (ca. 1485/90?–1576)". Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Metropolitan Museum of Art. October 2003. Retrieved 30 January 2011.

- ^ Pliny the Younger, Letters 9.23.

- ^ Wolf, Norbert (2006). I, Titian. New York and London: Prestel. ISBN 9783791333847.

- ^ Fossi, Gloria, Italian Art: Painting, Sculpture, Architecture from the Origins to the Present Day, p. 194. Giunti, 2000. ISBN 88-09-01771-4

- ^ Wethey, Harold Edwin (1969). The Paintings of Titian: The Religious Paintings. Vol. 1. Phaidon. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-7148-1393-6.

- ^ Cecil Gould, The Sixteenth Century Italian Schools, National Gallery Catalogues, p. 265, London, 1975, ISBN 0-947645-22-5

- ^ a b Cole, Bruce (2018) [1999]. Titian And Venetian Painting, 1450-1590. Routledge. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-429-96418-3.

- ^ Sohm, Philip Lindsay (2007). The Artist Grows Old: The Aging of Art and Artists in Italy, 1500-1800. Yale University Press. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-300-12123-0.

- ^ Hope, Charles (2008). "Titian's Family and the Dispersal of his Estate". In Ferino-Pagden, Sylvia; Scire, Giovanna Nepi (eds.). Late Titian and the Sensuality of Painting. Rizzoli International Publications. p. 29. ISBN 978-88-317-9412-1.

- ^ Joannides, Paul (2001). Titian to 1518: The Assumption of Genius. Yale University Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-300-08721-5.

- ^ a b Nichols, Tom (1 January 2013). "The Master as Monument: Titian and His Images". Artibus et Historiae: An Art Anthology: 225–229.

- ^ a b c Joannides, Paul (2001). Titian to 1518: The Assumption of Genius. Yale University Press. pp. 10–11. ISBN 978-0-300-08721-5.

- ^ Cole, Bruce (2018) [1999]. Titian And Venetian Painting, 1450-1590. Routledge. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-429-96418-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gillet, Louis (1912). "Titian". In Herbermann, Charles George (ed.). The Catholic Encyclopedia: An International Work of Reference on the Constitution, Doctrine, Discipline, and History of the Catholic Church. Vol. 14. Robert Appleton Company. pp. 744–745.

- ^ Freedberg, Sydney Joseph (1993). Painting in Italy, 1500-1600. Yale University Press. p. 345. ISBN 978-0-300-05587-0.

- ^ Joannides, Paul (2001). Titian to 1518: The Assumption of Genius. Yale University Press. p. 127. ISBN 978-0-300-08721-5.

- ^ Jaffé No. 1, pp. 74–75 image

- ^ a b "visitazione (dipinto) - ambito veneziano" [visitation (painting) - Venetian school]. Catalogo generale dei Beni Culturali (in Italian). Ministero della Cultura. 1998. Retrieved 23 May 2025.

- ^ "The Visitation". Gallerie dell'Accademia di Venezia, Official Website. Gallerie dell'Accademia. Retrieved 23 May 2025.

- ^ Joannides, Paul (2001). Titian to 1518: The Assumption of Genius. Yale University Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-300-08721-5.

- ^ "Portrait of Gerolamo (?) Barbarigo, about 1510, Titian". National Gallery. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ^ Williams, Hilary (2009). Rembrandt on Paper. Getty Publications. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-89236-973-7.

- ^ Romano, Dennis (2023). Venice: The Remarkable History of the Lagoon City. Oxford University Press. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-19-085998-5.

- ^ Joannides, Paul (2001). Titian to 1518: The Assumption of Genius. Yale University Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-300-08721-5.

- ^ Gould, Cecil (2016). Titian: (Grove Art Essentials). Oxford University Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-19-029796-1.

- ^ Brown, David Alan; Ferino-Pagden, Sylvia; Anderson, Jaynie; Howard, Deborah (2006). "Venetian Painting and the Invention of Art". Bellini, Giorgione, Titian, and the Renaissance of Venetian Painting. Yale University Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-300-11677-9.

- ^ Charles Hope, in Jaffé, 2003, pp. 11–14

- ^ Nichols, Tom (2013). Titian: And the End of the Venetian Renaissance. Reaktion Books. p. 149. ISBN 978-1-78023-227-0.

- ^ "New findings in Titian's Fresco technique at the Scuola del Santo in Padua", The Art Bulletin, March 1999, Volume LXXXI Number 1, Author Sergio Rossetti Morosini

- ^ a b c d e Tietze-Conrat, E. (September 1945). "Titian's "Battle of Cadore"". The Art Bulletin. 27 (3): 205–208. doi:10.2307/3047014. JSTOR 3047014.

- ^ Nichols 2013 p. 30

- ^ Brown, Patricia Fortini (1988). Venetian Narrative Painting in the Age of Carpaccio. Yale University Press. pp. 275–276 notes 14a–24. ISBN 978-0-300-04743-1.

- ^ Joannides 2001 p. 164

- ^ Joannides 2001 p. 164

- ^ Cole, Bruce (2010). "Titian: An Introduction". In Bondanella, Julia Conway; Bondanella, Peter; Cole, Bruce; Shiffman, Jody Robin (eds.). The Life of Titian. Penn State Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-271-04053-0.

- ^ "Titian | National Gallery of Art". www.nga.gov. 7 May 2025. Retrieved 26 May 2025.

- ^ Charles Hope, in Jaffé, 2003, p. 14

- ^ Cole, Bruce (2018) [1999]. Titian And Venetian Painting, 1450-1590. Routledge. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-429-96418-3.

- ^ Charles Hope, in Jaffé, 2003, pp. 16–17

- ^ Humfrey, Peter; Sherman, Allison (2015). "The Lost Church of San Niccolò ai Frari (San Nicoletto) in Venice and its Painted Decoration". Artibus et Historiae (72). ProQuest 1764327119.

- ^ Ruso, Anita (26 April 2018). "The community of Ragusa (Dubrovnik) in Genua and their chapel of Saint Blaise in Santa Maria di Castello". Il Capitale Culturale. Studies on the Value of Cultural Heritage. 2 (7): 72. doi:10.13138/2039-2362/1848.

- ^ Trška, Tanja (2023). "Pierantonio Palmerini's Altarpiece for the Church of St Saviour in Dubrovnik". Dubrovnik Annals. 27: 21, note 51. doi:10.13138/2039-2362/1848.

- ^ Freedman, Luba (January–June 1998). ""Saint Sebastian in Veneto Painting: The 'Signals' Addressed to 'Learned' Spectators" (PDF). Venezio Cinquecento: Studi di storia dell'arte e della cultura. 8 (15). Rome: 11, 13, 15.

- ^ Talvacchia, Bette (2010). "The Double Life of St. Sebastian in Renaissance Art". In Hairston, Julia L.; Stephens, Walter (eds.). The Body in Early Modern Italy. JHU Press. p. 364, note 2. ISBN 978-0-8018-9414-5.

- ^ Rosand, David (1994). "Titian's Saint Sebastians". Artibus et Historiae. 15 (30): 27, 29. doi:10.2307/1483471. JSTOR 1483471.

- ^ Getty Museum Staff (1988). "Acquisitions/1987". The J. Paul Getty Museum Journal. 16. Getty Publications. ISBN 978-0-89236-143-4.

- ^ Brown, Katherine T. (2024). Arboreal Symbolism in European Art, 1300–1800. Taylor & Francis. p. 89. ISBN 978-1-040-09848-6.

- ^ Charles Hope, in Jaffé, p. 17 Engraving of the painting

- ^ Jaffé, 2003, pp. 100–111

- ^ a b Syson, Luke (2008). "Belle: Picturing Beautiful Women". Art and Love in Renaissance Italy | Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 247. ISBN 978-1-58839-300-5.

- ^ Pericolo, Lorenzo (2009). "Love in the Mirror: A Comparative Reading of Titian's Woman at Her Toilet and Caravaggio's Conversion of Mary Magdalene". I Tatti Studies in the Italian Renaissance. 12: 175–177. doi:10.1086/its.12.27809574. ISSN 0393-5949. JSTOR 27809574. Retrieved 28 May 2025.

- ^ "Titian | Bacchus and Ariadne | NG35 | National Gallery, London". www.nationalgallery.org.uk. The National Gallery. 2025. Retrieved 28 May 2025.

- ^ Colantuono, Anthony (2017). "The Libido in Springtime: Titian's Bacchus and Ariadne". "Titian, Colonna and the Renaissance Science of Procreation ": Equicola's Seasons of Desire. Routledge. pp. 75–76. ISBN 978-1-351-53902-9.

- ^ Scott, David A. (2016). Art: Authenticity, Restoration, Forgery. Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press. p. 338. ISBN 978-1-938770-41-8.

- ^ Loh 2019, p. 36

- ^ Rearick, W. R. (1991). "Titian Drawings: A Progress Report". Artibus et Historiae. 12 (23): 29. doi:10.2307/1483364. JSTOR 1483364.

- ^ Wethey, Harold Edwin (1969). The Paintings of Titian: The Religious Paintings. Vol. 1. Phaidon. pp. 48–49. ISBN 978-0-7148-1393-6.

- ^ Kravitz-Lurie, Esthy (2022). "'Un disio sol d'eterna gloria e fama': A Literary Approach to Titian's Allegory". In Unger, Daniel M. (ed.). Titian's Allegory of Marriage: New Approaches. Amsterdam University Press. pp. 55–56. doi:10.5117/9789463729536_ch05. ISBN 978-90-485-5216-0.

- ^ Unger, Daniel M. (2022). "Introduction: Poetic License". In Unger, Daniel M. (ed.). Titian's Allegory of Marriage: New Approaches. Amsterdam University Press. pp. 18–19.

- ^ Friedlaender, Walter (March 1965). "Titian and Pordenone". The Art Bulletin. 47 (1): 118–119. doi:10.2307/3048237. JSTOR 3048237.

- ^ "Drawing by Peter Paul Rubens". britishmuseum.org/. The British Museum. 2025. Retrieved 26 May 2025.

- ^ Jardine, Lisa (1998). Worldly Goods: A New History of the Renaissance. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-393-31866-1.

- ^ Loh, Maria H. (2007). Titian Remade: Repetition and the Transformation of Early Modern Italian Art. Getty Publications. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-89236-873-0.

- ^ a b Janson, Horst Woldemar; Janson, Anthony F. (2004). History of Art: The Western Tradition. Prentice Hall. pp. 42–43. ISBN 978-0-13-182895-7.

- ^ a b Huse, Norbert; Wolters, Wolfgang (1990). The Art of Renaissance Venice: Architecture, Sculpture, and Painting, 1460-1590. University of Chicago Press. pp. 327–328. ISBN 978-0-226-36109-3.

- ^ Campbell, Stephen J. (2019). The Endless Periphery: Toward a Geopolitics of Art in Lorenzo Lotto's Italy. University of Chicago Press. p. 250. ISBN 978-0-226-48159-3.

- ^ de Armas, Frederick (2013). "The Artful Gamblers". In Barnard, Mary E.; de Armas, Frederick A. (eds.). Objects of Culture in the Literature of Imperial Spain. University of Toronto Press. p. 74. ISBN 978-1-4426-4512-7.

- ^ Clarke, Kenneth (1970). Masterpieces of Fifty Centuries | Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York, NY: Dutton. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-525-03950-1.

- ^ a b Falomir, Miguel (1 September 2023). "Titian, Philip II, and the Poesie : The Artist, the Patron, the Paintings". I Tatti Studies in the Italian Renaissance. 26 (2): 179–201. doi:10.1086/726847.

- ^ Kaufmann, Thomas DaCosta (April 2012). "Representation, Replication, Reproduction: The Legacy of Charles V in Sculpted Rulers' Portraits of the Sixteenth and Early Seventeenth Century". Austrian History Yearbook. 43: 4. doi:10.1017/S0067237811000555.

- ^ Cole, Bruce (2018) [1999]. Titian And Venetian Painting, 1450-1590. Routledge. p. 100. ISBN 978-0-429-96418-3.

- ^ Crowe, J. A. (Joseph Archer); Cavalcaselle, G. B. (Giovanni Battista) (1877). Titian: His Life and Times. With Some Account of His Family. Vol. 1. London : J. Murray.

His children are raised to the rank of Nobles of the Empire, with all the honours appertaining to families with four generations of ancestors.

- ^ Buonanno, Lorenzo G. (2022). The Performance of Sculpture in Renaissance Venice. Routledge. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-000-54049-9.

- ^ Nichols, Tom (2013). Titian: And the End of the Venetian Renaissance. Reaktion Books. p. 55. ISBN 978-1-78023-227-0.

- ^ Puttfarken, Thomas (2005). Titian & Tragic Painting: Aristotle's Poetics and the Rise of the Modern Artist. Yale University Press. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-300-11000-5.

- ^ Cole, Bruce (1999). Titian and Venetian painting, 1450-1590. Icon Editions. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-06-430905-9.

- ^ Bostock, Sophie (2012). "The Portrait of the Artist as an Old Man-with Emphasis on Titian". In Classen, Albrecht (ed.). Old Age in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance: Interdisciplinary Approaches to a Neglected Topic. Walter de Gruyter. p. 525. ISBN 978-3-11-092599-9.

- ^ Watts, Karen (2022). "The Arms and Armour of Titian's Allegory of Marriage". Titian's Allegory of Marriage: New Approaches. Amsterdam University Press. p. 100. ISBN 978-90-485-5216-0.

- ^ Corsato, Carlo (1 January 2016). "Titian's Pensions and the Rediscovery of the Original Royal Privilege of 1571". Studi Tizianeschi. IX: 99–100.

- ^ Crowe, J. A. (Joseph Archer); Cavalcaselle, G. B. (Giovanni Battista) (1877). Titian: His Life and Times: With Some Account of His Family. Vol. 2. London : J. Murray. p. 74.

- ^ Lonzi, Letizia (2017). Sulle tracce dei Vecellio. La famiglia, la bottega, gli affari, i contesti; e la storiografia cadorina (PDF). p. 113 note 354.

La località Col di Manza, dove Tiziano possedeva una casa, si trovava invece sotto la Podesteria di Ceneda.

- ^ Clark, Kenneth (2023). The Nude: A Study in Ideal Form. Princeton University Press. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-691-25289-6.

- ^ Calvillo, Elena (2013). "Authoritative Copies and Divine Originals: Lucretian Metaphor, Painting on Stone, and the Problem of Originality in Michelangelo's Rome". Renaissance Quarterly. 66 (2): 492. doi:10.1086/671584.

- ^ Calvillo, Elena (2018). "'Un paragone con oro su': Material Innovation, Invention and Sebastiano del Piombo's Papal Portraiture". Almost Eternal: Painting on Stone and Material Innovation in Early Modern Europe. BRILL. pp. 116–118. ISBN 978-90-04-36149-2.

- ^ Tagliaferro, Giorgio (2008). "In the Workshop With Titian". In Ferino-Pagden, Sylvia; Scire, Giovanna Nepi (eds.). Late Titian and the Sensuality of Painting. Rizzoli International Publications. p. 71. ISBN 978-88-317-9412-1.

- ^ a b Tagliaferro, Giorgio (2007). "Introduction: the Composition of Themes and Variations by Titian and His Workshop" (PDF). In Humfrey, Peter (ed.). Titian: Themes and Variations. pp. 12–14.

- ^ Cole, Bruce (1995). "Titian and the Idea of Originality". Georgia Museum of Art | The Craft of Art: Originality and Industry in the Italian Renaissance and Baroque Workshop. University of Georgia Press. p. 92. ISBN 978-0-8203-1648-2.

- ^ "Tagliaferro2007 p. 25"

- ^ Joannides, Paul (2016). "An Attempt to Situate Titian's Paintings of the Penitent Magdalen in Some Kind of Order". Artibus et Historiae (73). Cracow: 177.

- ^ Dunkerton, Jill; Spring, Marika; Billinge, Rachel; Kalinina, Kamilla; Morrison, Rachel; Macaro, Gabriella; Peggie, David; Roy, Ashok (2013). Roy, Ashok (ed.). "Titian's Painting Technique before 1540" (PDF). National Gallery Technical Bulletin. 34. Yale University Press: 19.

- ^ Penny, 204

- ^ Museo del Prado, Catálogo de las pinturas, 1996, p. 402, Ministerio de Educación y Cultura, Madrid, ISBN 84-87317-53-7

- ^ Penny, 249–50

- ^ Hughes-Hallett, Lucy (2024). The Scapegoat: The Brilliant Brief Life of the Duke of Buckingham. HarperCollins Publisher, p. 326.

- ^ Hughes-Hallett, Lucy (2024), pp. 328-329.

- ^ "Separated For Centuries, Titian's 'Poesie' Reunite At The Gardner Museum In A Powerful Exhibition". WBUR. 16 August 2021.

- ^ Cotter, Holland (12 August 2021). "Can We Ever Look at Titian's Paintings the Same Way Again?". The New York Times.

- ^ "Titian Comes Together"

- ^ Robertson, Giles (1983). Martineau, Jane; Hope, Charles (eds.). The Genius of Venice 1500-1600. London : Royal Academy of Arts, in association with Weidenfeld and Nicolson. pp. 231–233. ISBN 978-0-297-78322-0.

- ^ Jaffé, Michael, 1983, pp. 229–230

- ^ Rosand, David (1982). "Titian and the Critical Tradition". In Rosand, David (ed.). Titian, His World and His Legacy. New York : Columbia University Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-231-05300-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link) - ^ Hope, Charles (2008). "Titian's Family and the Dispersal of his Estate". In Ferino-Pagden, Sylvia; Scire, Giovanna Nepi (eds.). Late Titian and the Sensuality of Painting. Rizzoli International Publications. pp. 30–32. ISBN 978-88-317-9412-1.

- ^ "Titian Madonna and Child sells for record $16.9m". BBC News Online. 28 January 2011. Retrieved 30 January 2011.

- ^ "Art and the Bible". Artbible.info. Retrieved 30 January 2011.

- ^ Rossetti 1911, p. 1024.

- ^ Kennedy, Ian G. (2006). Titian, Circa 1490-1576. Taschen. p. 95. ISBN 978-3-8228-4912-5.

- ^ a b De La Rosa, Juan Eugenio (2011). "In Paint, Stone, and Memory: The Tomb of Titian and the Habsburg Dynasty". Athanor. 29: 69. ISSN 0732-1619.

- ^ Rosand Library Staff (2025). "Titian's Pietà and Frame in the Gallerie dell'Accademia". Save Venice. Rosand Library. Retrieved 31 May 2025.

- ^ Hale 2012, 722-723

- ^ Catra, Elena (2017). "Il cenotafio ad Antonio Canova (1822-1827) e il Monumento a Tiziano Vecellio". In Catra, Elena; Collavizza, Isabella; Pajusco, Vittorio (eds.). Canova, Titian and the Church of Frari in Venice in the 19th century (PDF) (in Italian). ZeL edizioni. p. 22. ISBN 978-88-87186-04-8.

- ^ Loh, Maria H. (2019). Titian's Touch: Art, Magic and Philosophy. Reaktion Books. pp. 18–19. ISBN 978-1-78914-109-2.

- ^ Hale 2012, 215

- ^ Loh 2019, p.123

- ^ Hale 2012, 249

- ^ Hale 2012, 486

- ^ Matino, Gabriele (6 March 2020). ""Et de presente habita ser vetor scarpaza depentor": new documents on Carpaccio's house and workshop at San Maurizio". Colnaghi Studies Journal, 06 March 2020 (PDF). London: Colnaghi Foundation. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-91622-941-9.

- ^ Loh 2019, p. 123

- ^ Salomon, Xavier F. (20 September 2019). "'An important work by Titian has been hiding in plain sight'". Apollo Magazine. Archived from the original on 21 September 2019. Retrieved 31 May 2025.

- ^ Hale 2012, 229

- ^ Cottrell, Philip (6 August 2021). "Aretino and the Painters of Venice". In Marco, Faini; Ugolini, Paola (eds.). A Companion to Pietro Aretino. The Renaissance Society of America, Volume: 18. p. 140. doi:10.1163/9789004465190_008. ISBN 978-90-04-34805-9.

- ^ Nichols, Tom (1999). Tintoretto: Tradition and Identity. Reaktion Books. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-86189-120-4.

- ^ Vellodi, Kamini (June 2015). "Tintoretto's Time" (PDF). Art History. 38 (3): 7 (420). doi:10.1111/1467-8365.12131.

- ^ Ilchman, Frederick (28 August 2018). "The triumph of Tintoretto". Apollo Magazine.

- ^ Freedberg, Sydney Joseph (1993). Painting in Italy, 1500-1600. Yale University Press. pp. 345–346. ISBN 978-0-300-05587-0.

- ^ Rosand Library Staff (2025). "Francesco Vecellio and Titian's Madonna and Child with Angels in the Church of Santa Maria Annunziata, Sedico". Save Venice. Rosand Library. Retrieved 31 May 2025.

- ^ D'Incà, Elia; Matino, Gabriele (2011). "Regesto per Francesco Vecellio" (PDF). Studi Tizianeschi. VI–VII. Università di Verona: 22.

- ^ "ULAN Full Record Display (Getty Research)". www.getty.edu. Getty Conservation Research Foundation Museum. 2025. Retrieved 1 June 2025.

- ^ [Le maraviglie dell'arte: ovvero Le vite degli illustri pittori], Volume 1, by Carlo Ridolfi, Giuseppe Vedova, page 288.

- ^ Ridolfi and Vedova, page 289.

- ^ Boni, Filippo de' (1840). Biografia degli Artisti, Emporeo biografico metodico, volume unico. Venice: Co' Tipi di Gondolieri. p. 703.

- ^ Nichols, Tom (2012). Renaissance Art in Venice: From Tradition to Individualism. Quercus Publishing. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-78627-116-7.

- ^ Nichols 2012, p. 179

- ^ Rosand, David (1981). "Titian and the Eloquence of the Brush". Artibus et Historiae. 2 (3): 85–86. doi:10.2307/1483103. JSTOR 1483103.

- ^ a b Ferino-Pagden, Sylvia (2008). Ferino-Pagden, Sylvia; Nepi Sciré, Giovanna (eds.). Late Titian and the Sensuality of Painting. Rizzoli International Publications, Incorporated. p. 15. ISBN 978-88-317-9412-1.

- ^ Rosand, David (1982). "Titian and the Critical Tradition". In Rosand, David (ed.). Titian, His World and His Legacy. New York : Columbia University Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-231-05300-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link) - ^ Dunkerton, Jill; Spring, Marika; Billinge, Rachel; Kalinina, Kamilla; Morrison, Rachel; Macaro, Gabriella; Peggie, David; Roy, Ashok (2013). Roy, Ashok (ed.). "Titian's Painting Technique before 1540" (PDF). National Gallery Technical Bulletin. 34. Yale University Press: 4–5.

- ^ Schmidt, Suzanne Karr. "Printed Bodies and the Materiality of Early Modern Prints," Archived 24 October 2020 at the Wayback Machine Art in Print Vol. 1 No. 1 (May–June 2011), p. 26.

- ^ Riggs, Arthur Stanley (1946). Titian the Magnificent and the Venice of His Day. Bobbs-Merrill Company. p. 96.

With the Paduan religious frescoes we encounter the name of Domenico Campagnola as Titian's assistant and associate. Very bad draughtsman, weak on composition, but seemingly a good copyist and lively imitator far more than an original painter, he was the steady collaborator of Titian in all his Paduan work...

- ^ Landau, 304–305, and in catalogue entries following. Much more detailed consideration is given at various points in: David Landau & Peter Parshall, The Renaissance Print, Yale, 1996, ISBN 0-300-06883-2

- ^ Jill Dunkerton and Marika Spring, with contributions from Rachel Billinge, Kamilla Kalinina, Rachel Morrison, Gabriella Macaro, David Peggie and Ashok Roy, Titian's Painting Technique to c. 1540, National Gallery Technical Bulletin, volume 34, 2013, pp. 4–31. Catalog I and II.

- ^ Pigments used by Titian, ColourLex

- ^ Scientific images of this painting are available, with explanations, on the website of the French Centre for Research and Restoration of the Museums of France).

- ^ Humfrey, Peter (2007). Titian: The Complete Paintings. [Ghent, Belgium] : New York, NY: Ludion ; Distributed in North America by Harry N. Abrams. p. 12. ISBN 9789055446889.

- ^ Woods-Marsden, Joanna (2009). "Titian: The Complete Paintings, Review". Renaissance Quarterly. 62 (1): 242–244. doi:10.1086/598479.

- ^ Carrell, Severin (2 February 2009). "Titian's Diana and Actaeon saved for the nation". The Guardian.

- ^ National Gallery Staff. "Titian | Diana and Callisto | NG6616 | National Gallery, London". www.nationalgallery.org.uk. The National Gallery. Archived from the original on 25 April 2025. Retrieved 2 June 2025.

Works cited

[edit]- Cole, Bruce (2018) [1999]. Titian And Venetian Painting, 1450-1590. Routledge. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-429-96418-3.

- Gould, Cecil, The Sixteenth Century Italian Schools, National Gallery Catalogues, London, 1975, ISBN 0-947645-22-5

- Hale, Sheila (2012). Titian : His Life. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-059876-1.

- Hope, Charles (2003). Jaffé, David (ed.). Titian: Catalogue published to accompany an exhibition at the National Gallery, London, 19 February–18 May 2003. London: National Gallery [u.a.] ISBN 1-85709-903-6.

- Landau, David, in Jane Martineau and Charles Hope (eds.), The Genius of Venice, 1500–1600, Royal Academy of Arts, London, 1983, ISBN 0810909855, ISBN 0297783238

- Penny, Nicholas, National Gallery Catalogues (new series): The Sixteenth Century Italian Paintings, Volume II, Venice 1540–1600, 2008, National Gallery Publications Ltd, ISBN 1-85709-913-3

- Ridolfi, Carlo (1594–1658), The Life of Titian, translated by Julia Conaway Bondanella and Peter E. Bondanella, Penn State Press, 1996, ISBN 0-271-01627-2, ISBN 978-0-271-01627-6

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Rossetti, William Michael (1911). "Titian". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 1023–1026.

Further reading

[edit]- Dalvit, Giulio and Peyton, Elizabeth, Titian's Man in a Red Hat, The Frick Collection, 2022, ISBN 978-1-913875-30-5

- Gayford, Martin, Venice: City of Pictures, London and New York: Thames & Hudson, 2024 (esp. ch. 5, "'Night and Day with Brush in Hand': Titian in the 1520s", and ch. 8, "'A New Path to Make Myself Famous': Titian in Old Age").

- Hall, James. The Self-portrait: A Cultural History. London: Thames & Hudson, 2014. ISBN 978-0-5002-3910-0

- Hope, Charles, Titian, New York: Harper & Row, 1980.

- Hudson, Mark, Titian: The Last Days, New York: Walker and Company, 2009. ISBN 978-0-8027-1076-5

- Loh, Maria H., Titian's Touch: Art, Magic and Philosophy, London: Reaktion Books, 2019, ISBN 978-1789140828, ISBN 178914082X

- Panofsky, Erwin (1969). Problems in Titian, Mostly Iconographic. New York University Press. ISBN 0714813257.

- Nichols, Tom, Titian and the End of the Venetian Renaissance, London: Reaktion Books, 2013. ISBN 978 1 78023 186 0

- Prose, Francine and Salomon, Xavier F., Titian's Pietro Aretino, The Frick Collection, 2020, ISBN 978-1-911-282-71-6

- Rossetti, William Michael (1888). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. XXIII (9th ed.). pp. 413–417.

External links

[edit]- 139 artworks by or after Titian at the Art UK site

- A closer Look at the Madonna of the Rabbit multimedia feature, Musée du Louvre official site (English version)

- The Titian Foundation Images of 168 paintings by the artist.

- Titian's paintings

- Tiziano Vecellio at Web Gallery of Art

- Christies' sale blurb for the recently restored 'Mother and Child'

- Bell, Malcolm The early work of Titian, at Internet Archive

- Titian at Panopticon Virtual Art Gallery

- How to Paint Like Titian James Fenton essay on Titian from The New York Review of Books

- Tiziano Vecellio - one of the greatest artists of all time

- Interactive high resolution scientific imagery of Titian's Portrait of a Woman with a Mirror from the C2RMF

- Titian: general resources, his paintings, and pigments used, ColourLex

- Teresa Lignelli, "Archbishop Filippo Archinto by Titian (cat. 204)," in The John G. Johnson Collection: A History and Selected Works, a Philadelphia Museum of Art free digital publication

- Titian's Filppo Archinto at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- The poesie exhibition at the National Gallery in London (16 March 2020 – 17 January 2021), the Museo del Prado in Madrid (2 March 2021 – 4 July 2021), and the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston (12 August 2021 – 2 January 2022)

- Titian

- 1480s births

- 1576 deaths

- 15th-century Italian painters

- 15th-century Venetian people

- 16th-century deaths from plague (disease)

- 16th-century Italian painters

- 16th-century Venetian people

- Burials at Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari

- Catholic painters

- Infectious disease deaths in Italy

- Italian male painters

- Italian Roman Catholics

- Italian Renaissance painters

- Painters from the Republic of Venice

- People from Pieve di Cadore

- Republic of Venice artists