User:M Waleed/sandbox

| This user loves Invincible (TV series) from the bottom of his heart |

Alt hist

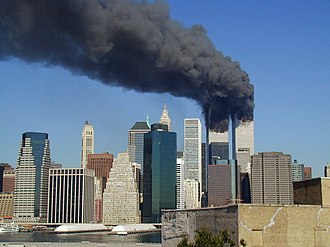

[edit]| United States invasion of Afghanistan | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War in Afghanistan (1995-1996) and war on terror | |||||||

Major American special forces operations in Afghan territory between February 1995 and March 1996 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Non-state allies: | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| 3,537–5,375 Afghan civilians killed[13] | |||||||

| Assassination of Pope John Paul II | |

|---|---|

Pope John Paul II in 1988 | |

| Location | Makati, Philippines |

| Date | 15 January 1995 |

| Target | Pope John Paul II |

Attack type | Suicide bombing |

| Deaths | 73 killed (during the suicide bombing) 1 killed (test bomb in Philippine Airlines Flight 434) |

| Injured | 127+ injured (during the suicide bombing) 10 injured (test bomb in Philippine Airlines Flight 434) |

| Perpetrators | Al-Qaeda and Jemaah Islamiyah |

| Accused | Khalid Sheikh Mohammed |

| Convicted | Ramzi Yusuf Abdul Hakim Murad Wali Khan Amin Shah |

| Operation Bojinka | |

|---|---|

| Location | Makati, Philippines (Phase I) London, United Kingdom, Paris, France and Airspace over Pacific Ocean (Phase II) Langley, New York City, Arlington, Washington, D.C., Chicago, Los Angeles, Detroit and San Francisco, U.S. (Phase III) |

| Date | January 15–22, 1995 |

| Target | Phase 1: Pope John Paul II Phase 2: 13 American airliners, four London Undergroundstrains, The Bataclan theatre, Boulevard Voltaire, Rue de Charonne, Rues Bichat and Alibert Phase 3: World Trade Center, Pentagon, United States Capitol, White House, Sears Tower, U.S. Bank Tower, Renaissance Center, Transamerica Pyramid and the CIA Headquarters |

Attack type | Islamic terrorism, suicide attack, bombing, mass murder, assassination and aircraft hijacking |

| Deaths | 13,450+ |

| Injured | 37,700-105,000+ |

| Perpetrators | Al-Qaeda and Jemaah Islamiyah, led by Osama bin Laden |

| Motive | United States foreign policy in the Middle East Anti-Christian sentiment |

| COVID-19 pandemic | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Confirmed deaths per 100,000 population

as of 20 December 2023 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Disease | Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) | ||||||

| Virus strain | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‑CoV‑2) | ||||||

| Source | Bats[14] (indirectly)[15] | ||||||

| Location | China (Minor spread Worldwide) | ||||||

| Index case | Wuhan, China 30°37′11″N 114°15′28″E / 30.61972°N 114.25778°E 1 December 2019 (5 years, 7 months and 2 days ago) | ||||||

| Dates | Assessed by WHO as pandemic: 11 March 2020 (5 years and 3 months ago)[16] | ||||||

| Confirmed cases | 775,866,783[17] (true case count is expected to be much higher)[18] | ||||||

Deaths | 7,057,132[17] (reported) 18.2–33.5 million[19] (estimated) | ||||||

| Fatality rate | As of 10 March 2023: 1.02%[20] | ||||||

Freikorps

[edit]uk:Фрайкор (добровольчий підрозділ)

It was established as a nationalist organization by a former member of the National Corps, Heorhiy Tarasenko on 21 May 2017, aiming to participate in the War in Donbass, the organization gained support "Sirko" of the Ukrainian Volunteer Corps who connected them with the fighters of the 57th Motorized Brigade. The personnel were deployed for combat on 13 July 2017 for the first time and remained deployed for 22 months seeing combat in Donetsk, Mariupol and near Kharkiv,[21] specifically seeing combat in Pisky, Pavlopil and repelling separatist assaults in Avdiivka, seeing action as part of the Joint Forces Operation.[22] Freikorps kept on closing in the "gray zone" and strengthening the front line. Initially, in 2017, together with the 57th brigade, they advanced about one kilometer forward. In 2017, the distance to the enemy positions which was initially 2-2.5 kilometers was reduced to 500-700 meters.[22] The organization increased it's strength and manpower and continued partaking in combat operations. The commander of the stronghold, to which the Freikorps was deployed in 2017 during storming of separatist positions in Donetsk, became a platoon commander of Freikorps. The Freikorps organization was registered in Kharkiv on 19 March 2018.[21] In June 2019, Freikorps together with other associations such as"Tradition and Order", Right Sector and National Corps held a demonstration during the congress of the "Trust in Affairs" party, after which they destroyed the bust of Georgy Zhukov by knocking it over and placed a Ukrainian flag at it's place.[23] In March 2021, it held patriotic education lessons at Kharkiv Gymnasium No. 43.[24]

Following the start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, it saw heavy combat. During the war, Freikorps captured a lot of heavy equipment, including MT-LBs and 152-mm self-propelled gun, but exchanged for lighter equipment like 120-mm mortar.[22] It saw heavy action especially in Kharkiv.[25] On 24 February, Freikorps took up positions on Northern Saltivka with a strength of about 20 people and handed over these positions later to Ukrainian Armed Forces and themselves took up positions on the Ring Road.[22] On 25 February, the personnel of Freikorps prepared RPGs against tank assaults and on 27 February, a column of Russian "Tigers" with the letters "Z" arrived and it's detachments went to intercept the at the 134th school.[22] First, the 92nd Brigade halted the column forcing Russians to abandon the vehicles. Freikorps' tasks included clearing the road along Shevchenko Street, a main road to North Saltivka with a major assault being expected from Saltivka. The Russians, having occupied the school no 134, blocked a main overpass making logistics nearly impossible.[22] Ultimately, Russian forces were driven out the Russian forces from the premises of School No. 134 by Freikorps and other units.[26] Then, freikorps took up defense along the Ring Road, preparing for an expected besiegement.[22] After the Russian Armed Forces were driven out of Kharkiv, the unit participated in battles for Mala Rohan, Sorokivka, Peremoha and Vesele.[22] Freikorps took part in the 2022 Kharkiv counteroffensive with the first combat being seen in Balakliia, the Freikorps entered from the western part of the city, established positions on the Balakliia River, occupied river crossings and paved the way for heavy equipment following which they established a bridgehead for other units to arrive and continued clearance operations.[22] It later also saw combat during offensive operation towards Kupyansk and Vovchansk.[22]

92nd Support Battalion

[edit]uk:92-й окремий батальйон підтримки

| 92nd Support Battalion | |

|---|---|

| 92-й окремий батальйон підтримки | |

| |

| Founded | 2024 |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Battalion |

| Role | Engineering |

| Size | ~200 |

| Part of | Support Forces Command |

| Engagements | |

The 92nd Support Battalion (MUN A4934)[27] is a battalion level military unit of the Ukrainian Support Forces, part of the Armed Forces of Ukraine. It has seen combat during the Russian invasion of Ukraine being involved in engineering, demining and CBRN warfare tasks.

History

[edit]It saw combat during the Russian invasion of Ukraine. On May 25, 2024, a soldier of the battalion (Igor Rutkovsky Ivanovich) was killed in combat in Donetsk Oblast.[28][29][30] In February 2024, it started a fundraiser campaign for a locker mobile workshop with half the finding completed by May[31] and fully in July 2024 and the vehicle was transferred to the battalion.[32]

Structure

[edit]- Management and Headquarters

- Engineering Department

- Support Department

- CBRN Defense Department[33]

- Commandant Platoon

16th Support Regiment

[edit]uk:16-й окремий полк підтримки (Україна)

| 16th Support Regiment | |

|---|---|

| 16-й окремий полк підтримки | |

| |

| Founded | 2018 |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Regiment |

| Role | Engineering |

| Part of | Operational Command South |

| Garrison/HQ | Semenivka |

| Engagements | |

The 16th Support Regiment (MUN A2558) is a regiment level military unit of the Ukrainian Support Forces, part of the Armed Forces of Ukraine's Operational Command South. It was established in 2018, but existed earlier as the engineering unit of the operational-tactical group "South". It is headquartered in Semenivka. It has seen combat during both, the War in Donbass and the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

History

[edit]It was established on the basis of the 28th Mechanized Brigade in Semenivka as part of Operational Command South. In November 2016, the operational-tactical group "South" held engineering exercises involving GMZ-3 minelayers and TDA-M smokescreen makers.[34] Further exercises in March 2017 also saw the use of RCBZ smokescreen makers.[35] In 2018, headquarters building was being constructed for the Regiment[36][37] and 4-story barracks, tankodrome, autodrome and other buildings were being constructed for the regiment.[38] The regiment also started a recruitment campaign.[39]

The regiment saw action during the War in Donbass. A serviceman of the regiment (Budnyk Oleg Vasilyevich) was killed in combat on 17 January 2019 by a landmine hitting his vehicle.[40]

Following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, it saw combat. Since November 2022, the Regiment has been conducting demining operations in the Mykolaiv Oblast and Kherson Oblast and also participated in combat operations such as the Battle of Krynky. On 28 January 2024, a soldier of the regiment (Vovk Ihor) was killed during battles in Kozachi Laheri.[41] A serviceman of the regiment (Andriy Olegovich Levytskyi) was killed in action on 24 December 2024 near Kizomys.[42][43][44][45]

Equipment

[edit]| Model | Image | Origin | Type | Number | Details |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicles | |||||

| GMZ-3 |

|

Minelayer | [34] | ||

| TDA-M |

|

Smokescreen | [34] | ||

| IMR-2 |

|

Heavy Combat engineering vehicle | [38] | ||

Commanders

[edit]- Colonel Kupchuk Oleksandr Ivanovych[46]

Structure

[edit]- Management and Headquarters

- 1st Engineering Battalion

- 2nd Engineering Battalion

- Personnel Department[47]

- Engineering Structures Department[47]

- Traffic Support Company[47]

- Commandant Platoon

Sources

[edit]- "Інженерні підрозділи ОТУ «Південь» готові до виконання завдань за призначенням". wartime.org.ua. Військова панорама. 2017-03-13. Archived from the original on 2017-09-23. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- "Українські сапери потренувалися боротися з ворожим морським десантом". 24tv.ua. 24 канал. 2016-12-05. Archived from the original on 16 January 2018. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- Підрозділи збройних сил поповнюються оновленою технікою РХБЗ Archived 6 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine

Afghan and Soviet warplanes in Pakistani airspace

[edit]Soviet Union and Democratic Republic of Afghanistan Air Force jet fighters and bombers would occasionally cross into Pakistani airspace to target Afghan refugees camps in Pakistan. To counter the Soviet jets, the United States started providing F-16 jets to Pakistan.[48] These F-16 jets lacked the capability to fire radar-guided beyond-visual range missiles, and thus they were required to get close to their opponents in order to use their AIM-9P and more advanced AIM-9L Sidewinder heat-seeking or their 20-millimeter Vulcan cannons. On 17 May 1986, two Pakistan Air Force (PAF) F-16 jets intercepted two Su-22M3K belonging to Democratic Republic of Afghanistan Air Force (DRAAF) near the Pakistani airspace.[48] Pakistani officials insisted that both the fighter jets belonging to DRAAF were shot down while Afghan officials confirmed loss of only one fighter jet. Following the engagement, there was a major decline in the number of attacks on Afghan refugees camps in Pakistan. On 16 April 1987, a group of PAF F-16s again chased down two DRAAF Su-22 and managed to shoot down one of them and capture its pilot.[48] In 1987, the Soviet Union reported that Pakistani fighter jets were roaming in Afghan airspace, harassing attempts to aerial resupply the besieged garrisons like the one in Khost. On 30 March 1987, two PAF F-16s shot down an An-26 cargo plane, killing all 39 personnel on board the aircraft. In the coming years, PAF claimed credit for shooting down several Mi-8 transport helicopters, and another An-26 which was on a reconnaissance mission in 1989.[48] Also in 1987, two PAF F-16 jets ambushed four Mig-23 which were bombing Mujahideen supply bases. In the clash, one PAF F-16 was lost after it was accidentally hit by an AIM-9 Sidewinder fired by the second PAF F-16. The PAF pilot landed in Afghanistan territory and was smuggled back to Pakistan along with wreckage of his aircraft by the Mujahideen. However, some Russian sources claim that the F-16 was shot down by a Mig-23, though the Soviet Mig-23 were not carrying air-to-air missiles.[48] On 8 August 1988, Colonel Alexander Rutskoy was leading a group of Sukhoi Su-25 fighter jets to attack a refugee camp in Miramshah, Pakistan. His fighter jet was intercepted and shot down by two PAF F-16. Colonel Alexander Rustkoy landed in Pakistani territory and was captured.[48] He was later exchanged back to the Soviet Union. A month later, around twelve Mig-23 crossed into Pakistani airspace with the aim to lure into ambush the Pakistani F-16s. Two PAF F-16s flew towards the Soviet fighter jets.[48] The Soviet radars failed to detect the low flying F-16s, and the Sidewinder fired by one of the F-16s damaged one of the Mig-23. However, the damaged Mig-23 managed to return home. Two Mig-23 engaged the two PAF F-16s. The Pakistani officials state that both the Mig-23 were shot down. However, Soviet records show that no additional aircraft were lost that day. The last aerial engagement took place on 3 November 1988, in which one Su-2M4K belonging to DRAAF was shot down by a Pakistani Air Force jet.[48] During the conflict, Pakistan Air Force F-16 had shot down ten aircraft, belonging to Soviet Union, which had intruded into Pakistani territory. However, the Soviet record only confirmed five kills (three Su-22s, one Su-25 and one An-26). Some sources show that PAF had shot down at least a dozen more aircraft during the war. However, those kills were not officially acknowledged because they took place in Afghanistan's airspace and acknowledging those kills would mean that Afghan airspace was violated by PAF.[48] In all, Pakistan Air Force F-16s had downed several MiG-23s, Su-22s, an Su-25, and an An-24 while losing only one F-16.[49]

- ^ "Uzbek Militancy in Pakistan's Tribal Region" (PDF). Institute for the Study of War. 27 January 2011. Retrieved 2023-11-30.

- ^ "Inside rebel Pakistan cleric's domain - USATODAY.com". USA Today. 2009-05-01. Archived from the original on May 1, 2009. Retrieved 2023-11-30.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Top Pakistani militant released". BBC News. 2008-04-21. Archived from the original on 2009-05-22. Retrieved 2023-11-30.

- ^ Whitlock, Craig (June 8, 2006). "Al-Zarqawi's Biography". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 20, 2012. Retrieved 2023-11-30.

- ^ Bergen, Peter. " The Osama bin Laden I Know, 2006

- ^ Malkasian 2021, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Malkasian 2021, p. 64.

- ^ a b Malkasian 2021, p. 78.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j m, p. 1.

- ^ a b c d Malkasian 2021, p. 63.

- ^ Coll 2019, p. 110.

- ^ Crawford 2011, p. 27.

- ^ Crawford 2011, p. 26.

- ^ Zoumpourlis V, Goulielmaki M, Rizos E, Baliou S, Spandidos DA (October 2020). "[Comment] The COVID‑19 pandemic as a scientific and social challenge in the 21st century". Molecular Medicine Reports. 22 (4): 3035–3048. doi:10.3892/mmr.2020.11393. PMC 7453598. PMID 32945405.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

who-origins-20210330was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

startwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Mathieu, Edouard; Ritchie, Hannah; Rodés-Guirao, Lucas; Appel, Cameron; Giattino, Charlie; Hasell, Joe; Macdonald, Bobbie; Dattani, Saloni; Beltekian, Diana; Ortiz-Ospina, Esteban; Roser, Max (2020–2024). "Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19)". Our World in Data. Retrieved 2025-04-01.

- ^ Mathieu E, Ritchie H, Rodés-Guirao L, Appel C, Giattino C, Hasell J, Macdonald B, Dattani S, Beltekian D, Ortiz-Ospina E, Roser M (5 March 2020). "Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19)". Our World in Data. Archived from the original on 24 February 2024. Retrieved 24 February 2024.

- ^ "The pandemic's true death toll". The Economist. 26 July 2023 [18 November 2021]. Archived from the original on 8 February 2024. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ^ "COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU)". ArcGIS. Johns Hopkins University. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- ^ a b Freikorps (Volunteer Unit)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j ""Ми були першими з добровольчих підрозділів, які 24 лютого прийшли на допомогу ЗСУ". Інтерв'ю з начальником штабу "Фрайкору" Богданом Войцеховським, - ФОТО". 057.ua. 24 November 2022. Archived from the original on 4 June 2024. Retrieved 7 September 2024.

- ^ "У Харкові повалили бюст Жукова, Кернес обіцяє відновити - BBC News Україна". BBC. 2 June 2019. Archived from the original on 9 January 2024. Retrieved 7 September 2024.

- ^ Tsvetkova, Sofia (3 March 2021). "У Харкові відсторонили директора школи, у якій "Фрайкор" провів урок патріотизму". Suspilne Kharkiv. Archived from the original on 9 March 2021. Retrieved 7 September 2024.

- ^ "Бійці «Фрайкору» тримають оборону Харкова!". Telegram. ФРАЙКОР ✙. 24 February 2022. Archived from the original on 2023-08-11. Retrieved 21 October 2023.

- ^ "Фрайкор разом з ЗСУ вибиває окупантів з приміщення школи!". Telegram. FRYKOR ✙. 27 February 2022. Archived from the original on 2023-08-10. Retrieved 21 October 2023.

- ^ 92nd Support Battalion

- ^ Тернопільщина втратила на фронті мужнього воїна

- ^ На Тернопільщині провели в останню дорогу двох воїнів

- ^ РУТКОВСЬКИЙ Ігор Іванович

- ^ "92-ий ОБП потребує ремонтну майстерню! Долучись". YouTube. Tviy Krok. 19 May 2024. Retrieved 20 July 2024.

- ^ Мобільна майстерня Locker для ремонту техніки для 92-го окремого батальйону підтримки

- ^ Помер під час відпустки: на Монастирищині попрощалися із захисником

- ^ a b c "На Херсонщині військові сапери вчились зупиняти ворожі танки". mil.gov.ua. Міністерство оборони України. 2016-11-27. Archived from the original on 29 November 2016. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- ^ "Інженерні підрозділи ОТУ «Південь» готові до виконання завдань за призначенням". mil.gov.ua. Міністерство оборони України. 2017-03-11. Archived from the original on 28 July 2017. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- ^ "В Мелитопольском районе создают новую воинскую часть". mv.org.ua. Місцеві вісті. 2018-01-10. Archived from the original on 12 January 2018. Retrieved 12 January 2018.

- ^ "На Мелітопольщині сформують нову військову частину". zp.depo.ua. Depo.ua. 2018-01-10. Archived from the original on 13 January 2018. Retrieved 12 January 2018.

- ^ a b "Для новой воинской части восстанавливают танкодром и автодром". mv.org.ua. Місцеві новини. 2018-02-08. Archived from the original on 8 February 2018. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- ^ "Армии нужны водители и саперы". Archived from the original on 24 February 2019. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- ^ "Відразу двох учасників бойових дій на сході України втратила Мелітопольщина". Archived from the original on 2 September 2019. Retrieved 17 September 2019. Archived 2019-09-02 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Карнаух, Наталія (3 February 2024). "На Львівщині 3 лютого попрощаються із вісьмома захисниками". Cуспільне Львів. Archived from the original on 3 February 2024. Retrieved 25 January 2025.

- ^ "На фронті загинув працівник ТРК "Люкс" Андрій Левицький". 24 Канал (in Ukrainian). 2024-12-24. Retrieved 2024-12-31.

- ^ "У Святвечір на війні загинув працівник львівської медіакомпанії". Апостроф (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 2024-12-31.

- ^ "Тернопільщина втратила Героїв Костянтина Хромова, Володимира Штокала, Андрія Левицького та Володимира Кутка - 20 хвилин". te.20minut.ua (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 2024-12-31.

- ^ "У Львові завтра попрощаються з двома захисниками". tvoemisto.tv. Retrieved 2024-12-31.

- ^ "У МЕЛІТОПОЛЬСЬКОМУ РАЙОНІ ТРИВАЄ РОЗБУДОВА ВІЙСЬКОВОЇ ЧАСТИНИ". ztv.zp.ua. Archived from the original on 25 February 2019. Retrieved 2019-02-24.

- ^ a b c Мелітопольський район зустрів головне державне свято з рекордним урожаєм зернових

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Roblin, Sebastian (16 March 2019). "Pakistan's F-16s Battled Soviet Jets – and Shot Down the Future Vice President of Russia". National Interest. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- ^ Nordeen, Lon O. (2010). Air Warfare in the Missile Age. Smithsonian Institution, 2010. p. 170. ISBN 978-1-58834-282-9. Retrieved 20 December 2019.