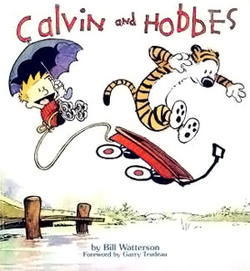

Calvin and Hobbes

| Calvin and Hobbes | |

|---|---|

Calvin and Hobbes took many wagon rides over the years—this one showed up on the cover | |

| Author(s) | Bill Watterson |

| Current status/schedule | Cancelled |

| Launch date | November 18, 1985 |

| End date | December 31, 1995 |

| Syndicate(s) | Universal Press Syndicate |

| Genre(s) | Humor |

Calvin and Hobbes was a daily comic strip written and illustrated by Bill Watterson, following the humorous antics of Calvin, an imaginative six-year old boy and Hobbes, his energetic and sardonic — albeit stuffed — tiger. The strip was syndicated from November 18, 1985 to December 31, 1995. At its height, Calvin and Hobbes was carried by over 2,400 newspapers worldwide. To date, more than 30 million copies of 18 Calvin and Hobbes books have been printed,[1] and popular culture is still replete with references to the strip.

The strip is vaguely set in the contemporary Midwestern United States, on the outskirts of suburbia, a location probably inspired by Watterson's home town of Chagrin Falls, Ohio. Calvin and Hobbes themselves appear in most of the strips, though several have focused instead upon Calvin's family. The broad themes of the strip deal with Calvin's flights of fantasy, his friendship with Hobbes, his misadventures, his views on a diverse range of political and cultural issues and his relationships and interactions with his parents, classmates, educators, and other members of society. A number af Calvin's adventures include polling his dad as a political figure. The dual nature of Hobbes is also a recurring motif; Calvin sees Hobbes as alive, while other characters see him as a stuffed animal, a point discussed more fully in Hobbes' main article. Unlike political strips such as Garry Trudeau's Doonesbury, the series does not mention specific political figures, but does examine broad issues like environmentalism and the flaws of opinion polls.[2]

Because of Watterson's strong anti-merchandising sentiments[3] and his reluctance to return to the spotlight, almost no legitimate Calvin and Hobbes licensed merchandise exists outside of the book collections. Some officially approved items were created for marketing purposes and are now sought by collectors.[4] Two notable exceptions to the licensing embargo were the publication of two 16-month wall calendars and the textbook Teaching with Calvin and Hobbes.[5]

However, the strip's immense popularity has led to the appearance of various "bootleg" items, including T-shirts, keychains, bumper stickers, and window decals, sometimes including obscene language or references contradicting or parodying the whimsical spirit of Watterson's work.

History

Calvin and Hobbes was first conceived when Watterson, having worked in an advertising job he detested,[6] began devoting his spare time to cartooning, his true love. He explored various strip ideas but all were rejected by the syndicates to which he sent them. However, he did receive a positive response on one strip, which featured a side character named Marvin (the main character's little brother) who had a stuffed tiger. Told that these characters were the strongest, Watterson began a new strip centered around them.[7] The syndicate (United Features Syndicate) which gave him this advice actually rejected the new strip, and Watterson endured a few more rejections before Universal Press Syndicate decided to take it.[8][3]

The first strip was published on November 18, 1985 and the series quickly became a hit. Within a year of syndication, the strip was published in roughly 250 newspapers. By April 1 1987, only sixteen months after the strip began, Watterson and his work were featured in an article by the Los Angeles Times, one of America's major newspapers.[3] Calvin and Hobbes twice earned Watterson the Reuben Award from the National Cartoonists Society, in the Outstanding Cartoonist of the Year category, first in 1986 and again in 1988. (He was nominated again in 1992.) Also, the Society awarded him the Humor Comic Strip Award for 1988.[9]

Before long, the strip was in wide circulation outside the United States; for more information on publication in various countries and languages, see Calvin and Hobbes in translation.

Watterson took two extended breaks from writing new strips — from May 1991 to February 1992, and from April through December of 1994.

In 1995, Watterson sent a letter via his syndicate to all editors whose newspapers carried his strip. It contained the following:

- I will be stopping Calvin and Hobbes at the end of the year. This was not a recent or an easy decision, and I leave with some sadness. My interests have shifted however, and I believe I've done what I can do within the constraints of daily deadlines and small panels. I am eager to work at a more thoughtful pace, with fewer artistic compromises. I have not yet decided on future projects, but my relationship with Universal Press Syndicate will continue.

- That so many newspapers would carry Calvin and Hobbes is an honor I'll long be proud of, and I've greatly appreciated your support and indulgence over the last decade. Drawing this comic strip has been a privilege and a pleasure, and I thank you for giving me the opportunity.

The 3,160th and final strip ran on Sunday, December 31, 1995.[10] It depicted Calvin and Hobbes outside in freshly-fallen snow, reveling in the wonder and excitement of the winter scene. "It's a magical world, Hobbes ol' buddy!" The last panel shows Calvin and Hobbes zooming off on their sled as Calvin exclaims. "Let's go exploring!" [11]

Syndication and Watterson's artistic standards

From the outset, Watterson found himself at odds with the syndicate, which urged him to begin merchandising the characters and touring the country to promote the first collections of comic strips; Watterson refused. To him, the integrity of the strip and its artist would be undermined by commercialization, which he saw as a major negative influence in the world of cartoon art.[12]

Watterson also grew increasingly frustrated by the gradual shrinking of available space for comics in the newspapers. He lamented that without space for anything more than simple dialogue or spare artwork, comics as an art form were becoming dilute, bland, and unoriginal.[13][12] Watterson strove for a full-page version of his strip (as opposed to the few cells allocated for most strips). He longed for the artistic freedom allotted to classic strips such as Little Nemo and Krazy Kat, and he gave a sample of what could be accomplished with such liberty in the opening pages of the Sunday strip compilation, The Calvin and Hobbes Lazy Sunday Book.[14]

During Watterson's first sabbatical from the strip, Universal Press Syndicate continued to charge newspapers full price to re-run old Calvin and Hobbes strips. Few editors approved of the move, but the strip was so popular that they had little choice but to continue to run it for fear that competing newspapers might pick it up and draw its fans away. Then, upon Watterson's return, Universal Press announced that Watterson had decided to sell his Sunday strip as an unbreakable half of a newspaper or tabloid page. Many editors and even a few cartoonists, such as Bil Keane (The Family Circus), criticized him for what they perceived as arrogance and an unwillingness to abide by the normal practices of the cartoon business—a charge that Watterson ignored. Watterson had negotiated the deal to allow himself more creative freedom in the Sunday comics. Prior to the switch, he had to have a certain number of panels with little freedom as to layout (due to the fact that in different newspapers the strip would appear at a different width); afterwards, he was free to go with whatever graphic layout he wanted, however unorthodox. His frustration with the standard space division requirements is evident in strips before the change; for example, a 1988 Sunday strip published before the deal is one large panel, but with all the action and dialogue in the bottom part of the panel so editors could crop the top part if they wanted to fit the strip into a smaller space. Watterson's explanation for the switch:

- I took a sabbatical after resolving a long and emotionally draining fight to prevent Calvin and Hobbes from being merchandised. Looking for a way to rekindle my enthusiasm for the duration of a new contract term, I proposed a redesigned Sunday format that would permit more panel flexibility. To my surprise and delight, Universal responded with an offer to market the strip as an unbreakable half page (more space than I'd dared to ask for), despite the expected resistance of editors.

- To this day, my syndicate assures me that some editors liked the new format, appreciated the difference, and were happy to run the larger strip, but I think it's fair to say that this was not the most common reaction. The syndicate had warned me to prepare for numerous cancellations of the Sunday feature, but after a few weeks of dealing with howling, purple-faced editors, the syndicate suggested that papers could reduce the strip to the size tabloid newspapers used for their smaller sheets of paper. … I focused on the bright side: I had complete freedom of design and there were virtually no cancellations.

- For all the yelling and screaming by outraged editors, I remain convinced that the larger Sunday strip gave newspapers a better product and made the comics section more fun for readers. Comics are a visual medium. A strip with a lot of drawing can be exciting and add some variety. Proud as I am that I was able to draw a larger strip, I don't expect to see it happen again any time soon. In the newspaper business, space is money, and I suspect most editors would still say that the difference is not worth the cost. Sadly, the situation is a vicious circle: because there's no room for better artwork, the comics are simply drawn; because they're simply drawn, why should they have more room?[15]

Despite the change, Calvin and Hobbes remained extremely popular and thus Watterson was able to expand his style and technique for the more spacious Sunday strips without losing carriers.

Since ending the strip, Watterson has kept aloof from the public eye and has given no indication of resuming the strip, creating new works based on the characters, or embarking on other projects. He refuses to sign autographs or license his characters, staying true to his stated principles. In previous years, he was known to sneak autographed copies of his books onto the shelves of a family-owned bookstore near his home in Chagrin Falls, Ohio. However, after discovering that some people were selling the autographed books on eBay for high prices, he ended this practice as well.

Merchandising

Bill Watterson is notable for his insistence that cartoon strips should stand on their own as an art form, and he has resisted the use of Calvin and Hobbes in merchandising of any sort.[8] This insistence stuck despite what was probably a cost of millions of dollars per year in additional personal income. Watterson explains in a 2005 press release:

- Actually, I wasn't against all merchandising when I started the strip, but each product I considered seemed to violate the spirit of the strip, contradict its message, and take me away from the work I loved. If my syndicate had let it go at that, the decision would have taken maybe 30 seconds of my life.[16]

Watterson did ponder animating Calvin and Hobbes, and has expressed admiration for the art form. In a 1989 interview in The Comics Journal, Watterson states:

- If you look at the old cartoons by Tex Avery and Chuck Jones, you'll see that there are a lot of things single drawings just can't do. Animators can get away with incredible distortion and exaggeration [...] because the animator can control the length of time you see something. The bizarre exaggeration barely has time to register, and the viewer doesn’t ponder the incredible license he's witnessed.

- In a comic strip, you just show the highlights of action — you can't show the buildup and release... or at least not without slowing down the pace of everything to the point where it's like looking at individual frames of a movie, in which case you've probably lost the effect you were trying to achieve. In a comic strip, you can suggest motion and time, but it's very crude compared to what an animator can do. I have a real awe for good animation.[12]

After this he was asked if it was "a little scary to think of hearing Calvin's voice." He responded that it was "very scary," and although he loved the visual possibilities animation had, the thought of casting voice actors to play his characters was something he felt uncomfortable doing. Plus, he wasn't sure he wanted to work with an animation team, as he'd done all previous work by himself. Ultimately, Calvin and Hobbes was never made into an animated series.

Except for the books, two 16-month calendars (1988–1989 and 1989–1990), and a children's textbook, virtually all Calvin and Hobbes merchandise, including T-shirts as well as the ubiquitous stickers for automobile rear windows which depict Calvin urinating on a company's or sports team's name or logo, is unauthorized. After threat of a lawsuit alleging infringement of copyright and trademark, some of the sticker makers replaced Calvin with a different boy, while other makers ignored the issue. Watterson wryly commented "I clearly miscalculated how popular it would be to show Calvin urinating on a Ford logo."[16] Some legitimate special items were produced, such as promotional packages to sell the strip to newspapers, but these were never sold outright.

Style and influences

Calvin and Hobbes strips are characterized by sparse but careful draftsmanship, intelligent humor, poignant observations, witty social and political commentary, and well-developed characters that are full of personality. Precedents to Calvin's fantasy world can be found in Charles M. Schulz's Peanuts, Percy Crosby's Skippy, Berkeley Breathed's Bloom County, and George Herriman's Krazy Kat, while Watterson's use of comics as sociopolitical commentary reaches back to Walt Kelly's Pogo. Schulz and Kelly in particular influenced Watterson's outlook on comics during his formative years.[8]

Notable elements of Watterson's artistic style are his characters' diverse and often exaggerated expressions (particularly those of Calvin), elaborate and bizarre backgrounds for Calvin's flights of imagination, well-captured kinetics, and frequent visual jokes and metaphors. In the later years of the strip, with more space available for his use, Watterson experimented more freely with different panel layouts, stories without dialogue, and greater use of whitespace. He also made a point of not showing certain things explicitly: the "Noodle Incident" and the children's book Hamster Huey and the Gooey Kablooie were left to the reader's imagination, where Watterson was sure they would be "more outrageous" than he could portray.[17]

Watterson's technique started with minimal pencil sketches (though the larger Sunday strips often required more elaborate work); he then would use a small sable brush and India ink to complete most of the remaining drawing. He was careful in his use of color, often spending a great deal of time in choosing the right colors to employ for the weekly Sunday strip.

Art and academia

Watterson has used the strip to criticize the artistic world, principally through Calvin's unconventional creations of snowmen. When Miss Wormwood complains that he is wasting class time drawing incomprehensible things (a Stegosaurus in a rocket ship, in fact), Calvin proclaims himself "on the cutting edge of the avant-garde". He begins exploring the medium of snow when a warm day melts his snowman. His next sculpture "speaks to the horror of our own mortality, inviting the viewer to contemplate the evanescense of life", much in the vein of Ecclesiastes. Over the years, Calvin's creative instincts diversify into sidewalk drawings ("suburban postmodernism").

Watterson also directed criticism toward the academic world. Calvin writes a "revisionist autobiography", giving himself a flame thrower. Another time, he carefully crafts an "artist's statement", knowing that such essays convey more messages than artworks themselves ever do ("You misspelled Weltanschauung," Hobbes blandly notes). He indulges in what Watterson calls "pop psychobabble" to justify his destructive rampages and shift blame to his parents, citing "toxic codependency." Once, he pens a book report entitled, "The dynamics of interbeing and monological imperatives in Dick and Jane: a study in psychic transrelational gender modes." Displaying his creation to Hobbes, he remarks, "Academia, here I come!" Watterson explains that he adapted this jargon (and similar examples from several other strips) from an actual book of art criticism.[17]

Overall, Watterson's satirical essays serve to attack both sides, criticizing both the commercial mainstream and the artists who are supposed to be "outside" it. Walking contemplatively through the woods, not long after he began drawing his "Dinosaurs in Rocket Ships Series", Calvin tells Hobbes,

- The hard part for us avant-garde post-modern artists is deciding whether or not to embrace commercialism. Do we allow our work to be hyped and exploited by a market that's simply hungry for the next new thing? Do we participate in a system that turns high art into low art so it's better suited for mass consumption?

- Of course, when an artist goes commercial, he makes a mockery of his status as an outsider and free thinker. He buys into the crass and shallow values art should transcend. He trades the integrity of his art for riches and fame.

- Oh, what the heck. I'll do it.

Such sentiments echo Watterson's own struggles with his Syndicate over merchandising issues.

Distorted reality

On several occasions, Watterson began a strip with a distorted view of reality: inverted colors, all objects turning "neo-Cubist", or the world turning to black-and-white without outlines, for example. Only Calvin and Hobbes are able to perceive these changes, which the reader can interpret as their way of seeing certain situations, issues and subjects which he has difficulty understanding or accepting.

In the Tenth Anniversary Book, Watterson acknowledges that most of these strips were metaphors for his own conflicts, typically against his syndicate's desire to produce Calvin and Hobbes merchandise. Accused of only seeing issues in "black and white" (Calvin's reply of "Sometimes that's the way things are!" was directly taken from his response to this accusation)—e.g., crass commercialism versus artistic integrity, with nothing in between—Watterson chose to illustrate the situation literally, dropping Calvin into a world where everything had lost shades of grey. Conversely, the "neo-Cubist" strip emerged from the way Watterson found himself "paralyzed by being able to see all sides of an issue".

Passage of time

When the strips were originally published, Calvin's settings were seasonally appropriate for the Northern hemisphere. Calvin would be seen building snowmen or sledding during the wintertime, and outside activities such as water balloon fights would replace school during the summer. Christmas and Halloween strips were run during those approximate times of year.

Although Watterson depicts several years' worth of holidays, school years, summer vacations, and camping trips, Calvin is never shown to age nor have any birthday celebrations (the only birthday shown was that of Susie Derkins). This is fairly common among comic strips; consider the children in Charles Schulz's Peanuts, most of whom existed without aging for decades. Likewise, the characters in George Herriman's Krazy Kat celebrate the New Year but never grow old, and young characters like Ignatz Mouse's offspring never seem to grow up. Since this is such a common phenomenon, readers are likely to suspend disbelief, as most of them do about Calvin's precocious vocabulary, accepting that he "was never a literal six-year-old".[17]

Social criticisms

In addition to his criticisms of art and academia, Watterson often used the strip to comment on American culture and society. As the strip avoids reference to actual people or events, Watterson's commentary is necessarily generalized. He expresses frustration with public decadence and apathy, with commercialism, and the pandering nature of the mass media. Calvin is often seen "glued" to the television, while his father speaks with the voice of the author, struggling to impart his values on Calvin.

Hobbes also speaks on Calvin's unwholesome habits, but from a more cynical perspective; he is more likely to make a wry observation than actually intervene. Sometimes he merely looks on as Calvin inadvertently makes the point himself. In one instance, Calvin tells Hobbes about a story in which machines turn humans into zombie slaves. He then exclaims, "My TV show is on!" and sprints from the room in a panic to watch it.

Contrariwise, at times Calvin is the one doing the criticizing of culture. For example, when Calvin and Hobbes stumble onto a heap of litter, they get angered at the people who pollute the world. Calvin had once said, in response to man's exploitation and destruction of nature, "I think the surest sign that intelligent life exists elsewhere in the universe is that none of it has tried to contact us," and "I wonder if you can refuse to inherit the world."

Calvin is also slightly misanthropic, given how some of the people in the world (particularly at school) cruelly treat him. Calvin admires how Hobbes isn't human, a sentiment which Hobbes shares.

The main characters

Calvin

Named after 16th century theologian John Calvin (founder of Calvinism and a strong believer in predestination), Calvin is an impulsive, imaginative, energetic, curious, intelligent, and often selfish six-year-old, whose last name the strip never gives. Despite his low grades, Calvin has a wide vocabulary range that rivals that of an adult as well as an emerging philosophical mind. "You know how Einstein got bad grades as a kid?" he says. "Well, mine are even worse!" He commonly wears his distinctive striped shirt. Watterson has described Calvin thus:

- "Calvin is pretty easy to do because he is outgoing and rambunctious and there's not much of a filter between his brain and his mouth."[18]

- "I guess he's a little too intelligent for his age. The thing that I really enjoy about him is that he has no sense of restraint, he doesn't have the experience yet to know the things that you shouldn't do."

- "The socialization that we all go through to become adults teaches you not to say certain things because you later suffer the consequences. Calvin doesn't know that rule of thumb yet."[12]

Calvinistic predestination as a philosophical position basically entails the idea that the human action affecting a person's ultimate salvation or damnation is predestined. Calvin's consistent gripe is that the troublesome acts he commits are outside of his control: he is simply a product of his environment, a victim of circumstances. He does frequently escape from his environment into elaborate fantasy worlds of his own creation; one of the strip's recurring devices is the humorous juxtaposition of Calvin's fantastic perception with the quotidian viewpoint of other characters. On many occasions, Calvin sees himself in one of his many alternate guises: as the superhero Stupendous Man, the astronaut and explorer Spaceman Spiff, the private eye Tracer Bullet, and many others (see Calvin's alter egos).

Hobbes

Hobbes is Calvin's stuffed tiger who, from Calvin's perspective, is as alive and real as anyone in the strip. He is named after 17th century philosopher Thomas Hobbes, who had what Watterson described as "a dim view of human nature." Hobbes is much more rational and aware of consequences than Calvin, but seldom interferes with Calvin's troublemaking beyond a few oblique warnings — after all, Calvin will be the one to get in trouble for it, not Hobbes. Hobbes also has the habit of regularly stalking and pouncing on Calvin, most often when Calvin returns home from school.

From Calvin's point of view, Hobbes is an anthropomorphic tiger, much larger than Calvin and full of his own attitudes and ideas. But when the perspective shifts to any other character, readers see merely a little stuffed tiger. This is, of course, an odd dichotomy, and Watterson explains it thus:

- When Hobbes is a stuffed toy in one panel and alive in the next, I'm juxtaposing the "grown-up" version of reality with Calvin's version, and inviting the reader to decide which is truer.[8]

Although the first strips clearly show Calvin capturing Hobbes by means of a snare (with tuna fish as the bait), a later comic (1 August 1989) seems to imply that Hobbes is, in fact, older than Calvin, and has been around his whole life. Watterson eventually decided that it was not important to establish how Calvin and Hobbes had first met.[17]

Supporting characters

Calvin's family

Calvin's mother and father are for the most part typical Middle American middle-class parents; like many other characters in the strip, their relatively down-to-earth and sensible attitudes serve primarily as a foil for Calvin's outlandish behavior. Both parents go through the entire strip unnamed, except as "Mom" and "Dad", or such pet names as "hon" and "dear." Watterson has never given Calvin's parents names "because as far as the strip is concerned, they are important only as Calvin's mom and dad." This ended up being somewhat problematic when Calvin's Uncle Max was in the strip for a week and couldn't refer to the parents by name, and was one of the main reasons that Max never again appeared.

Susie Derkins

Susie Derkins, the only character with both first and last names, is a classmate of Calvin who lives in his neighborhood. She first appeared early in the strip as a new student in Calvin's class. In contrast with Calvin, she is polite and diligent in her studies, and her imagination usually seems mild-mannered and civilized, consisting of stereotypical young girl games such as playing house or having tea parties with her stuffed animals. "Derkins" was the nickname of Watterson's wife's family beagle, and he liked the name so much he named this character after it. As much as either of them hate to admit, Calvin and Susie have quite a bit in common. (Susie is shown on occasion with a stuffed rabbit dubbed "Mr. Bun," and Calvin always has Hobbes.)

Watterson admits that Calvin and Susie have a bit of a nascent crush on each other (Said by Calvin, "It's shameless the way we flirt."), and that Susie is inspired by the type of women Watterson himself finds attractive (which has led to speculation that Susie is based on Watterson's wife). Her relationship with Calvin, though, is frequently conflicted, and never really becomes sorted out, and the closest things are times when Calvin sends dead flowers and hate-mail as Valentine's Day gifts for his own enjoyment. (She feels he likes her enough to send her that gift, and he rejoices in her noticing.)

On occasion, Hobbes takes action to attract Susie's romantic attention, often with success, and much to Calvin's chagrin. Although on the surface these scenarios take the form of Hobbes teasing Calvin and showing off his charms, they may be Calvin's way to disguise his own crush on Susie, by pretending that it is Hobbes' crush instead.

Miss Wormwood

Miss Wormwood is Calvin's world-weary teacher, named after the apprentice devil in C.S. Lewis's The Screwtape Letters. She perpetually wears polka-dotted dresses, and is another character who serves as a foil to Calvin's mischief. Calvin, when in his Spaceman Spiff persona, sees Miss Wormwood as a slimy, often dictatorial alien. She is waiting to retire, takes a lot of medication, and is apparently a heavy smoker and drinker.

Although there is a definite progression of time in the Calvin and Hobbes universe, mainly exhibited by the changing seasons, Calvin (and Susie) returns to Ms. Wormwood's first-grade class every fall.

Rosalyn

Rosalyn is a teen-age high-school senior and Calvin's official babysitter whenever Calvin's parents need a night out. She is the only babysitter able to tolerate Calvin's antics, which she uses to demand raises and advances from Calvin's desperate parents. She is also, according to Watterson, the only person Calvin truly fears—certainly she is his equal in cunning, and doesn't hesitate to play as dirty as he does. Despite being Calvin's nemesis, she is surprisingly good at playing Calvinball. Originally created as a nameless, one-shot character with no plans to appear again, Watterson decided he wanted to retain her unique ability to intimidate Calvin, which, ultimately, led to many more appearances.

Moe

Moe is the archetypical bully character in Calvin & Hobbes, ("a six-year-old who shaves") who is always shoving Calvin against walls, demanding his lunch money and calling him "Twinky." Moe is the only regular character who speaks in an unusual font: his (frequently monosyllabic) dialogue is shown in crude, lower-case letters. Watterson describes Moe as "every jerk I've ever known." And while Moe is not smart, he is, as Calvin puts it, streetwise. That means he knows what street he lives on.

Recurring subject matter

There are several repeating themes in the work, a few involving Calvin's real life, and many stemming from his incredible imagination. Some of the latter are clearly flights of fancy, while others, like Hobbes, are of an apparently dual nature and don't quite work when presumed real or unreal.

Mealtimes

Lunchtime and dinnertime find Calvin eager to share his thoughts about the food he (or anyone else) is eating. Those eating with him are generally repulsed by his colorful descriptions of the cuisine, which is one of the reasons his parents seldom take him to restaurants. During dinnertime at home, Calvin's meals are often depicted as unidentifiable blobs of green goo. Calvin is often repulsed, though his mother (or father) occasionally coaxes him to eat his dinner by informing him that they are in fact serving some outlandish or stomach-turning dish — e.g., toxic waste (which Calvin's father informs him will "turn you into a mutant if you eat it"), stewed monkey heads, spider pie ("You can pick out the legs and give them to your dad if they're too hairy for you" his mom quips), soup with maggots in it — which Calvin then eats with relish, (but rejects some meal which he classifies as "toad stroganoff") though his other parent usually no longer has an appetite. On occasion, once his parents are out of the room, his meals even become animate (sometimes growing a mouth and speaking), usually resulting in an epic fight with said food that leaves a large mess that strains his mother's patience.

One dinnertime, Calvin's meal actually performed Hamlet's "To be, or not to be" soliloquy in an overly histrionic style (at one point grabbing Calvin's fork and jamming it into itself during the speech about suicide). After the soliloquy, the meal returned to its inanimate blob-like state. After a brief pause (during which Calvin blinks several times), the same meal then suddenly began to sing "Feelings," prompting Calvin to eat it so quickly that his mom thought he liked it.

He also gives interesting commentary on his food during lunchtime at school, infuriating Susie. In one case these descriptions — specifically referring to the contents of Calvin's school lunch as "a thermos full of phlegm" — provoked a newspaper to cancel the strip. One time during lunchtime at school, Calvin sits down next to Susie and said, "Mmm mmm, lunchtime! And today's lunch is extra special! Ever since the weather got warm I've been swatting flies and saving them in a jar. I finally got enough flies to mash them into a gooey paste with a spoon." Calvin then takes out his sandwich and holds it up to Susie, grinning and saying, "I call it 'bug butter.' Care for a taste?" Susie, exasperated, leans her head on one hand and asks, "Tell me, Calvin, do you have any friends at all?"

Bathtime

To Calvin, bathtime is somewhat of a paradox: Trying to get Calvin into the bath on a nightly basis is a nearly impossible task for his mother, however, once in the water, Calvin often makes an imaginative game of it. He may envision himself as an underwater explorer (like Jacques Cousteau), an exotic or deadly sea creature (an octopus, shark, or Godzilla), or merely a diver enjoying a leisurely descent along a reef. Imitating a deadly creature is often a foil to his mother's attempts to instill a value of cleanliness in Calvin: while a shark, he may leap out of the water and snap viciously at his mother, (whose furious answer is "For someone who doesn't like baths, you aren't making this any easier!"). At other times, Calvin's behavior in the bath is merely implied, for instance when a naked and wet Calvin streaks past his father and moments later his mother appears, her clothes also soaking wet. He also has climbed out of his bath and walked down the stairs, claiming to be a 'nude descending a staircase'. Calvin has also tried alternative methods of bathing, such as standing in the toilet bowl and pulling the handle (this method proved to be a time-saver).

The Monsters Under the Bed

At night, Calvin is constantly terrorized by Monster/nightmare creatures apparently living under his bed. Only Calvin and Hobbes are aware of them (there are occasions on which they attempt to bribe Hobbes into handing Calvin over, often with food). There appears to be no continuing theme to their appearance except that they are very intimidating, but none too bright ("all teeth and digestive tract, no brains"), and they probably want to "squeeze" Calvin. The monsters are not always frightening: upon occasion, when frightened by something even scarier than monsters, Calvin and Hobbes turns on the lights and kills the monsters.

G.R.O.S.S.

G.R.O.S.S. is Calvin's anti-girl club, somewhat reminiscent of a South American-style banana republic. The name is an acronym that stands for Get Rid Of Slimy girlS (Calvin admits "slimy girls" is a bit redundant, as of course all girls are slimy, "but otherwise it doesn't spell anything"). Based in a treehouse (with occasional emergency meetings inside a cardboard box), the main objective of G.R.O.S.S. is to exclude girls, chiefly Calvin's neighbor Susie Derkins. Calvin and Hobbes are its only members, and wear newspaper chapeaux during meetings. Calvin and Hobbes spend most of their time in the club reworking its constitution and arguing about their bureaucratic roles and titles. Because the club exists specifically to harass girls, they sometimes plan missions to do so. After a mission they award themselves medals and promotions, regardless of their success. Calvin is G.R.O.S.S.'s "Supreme Dictator for Life", and Hobbes is "President and First Tiger." They also dub themselves different various ranks for the appropriate situation (and frequently switch roles between their respective ranks/characters in a situation). Their anthem is generally unknown, but begins: "Oh Gross, Best Club in the Cosmos". [19]

Cardboard boxes

Over the years Calvin has had quite a few adventures involving corrugated cardboard boxes, which he adapts for many different uses. His inventions include a Transmogrifier, a flying time machine and a duplicator.

Building a transmogrifier is accomplished by turning a cardboard box upside-down, attaching an arrow to the side and writing a list of choices on the box. Upon turning the arrow to a particular choice and pushing a button, the transmogrifier instantaneously rearranges the subject's "chemical configuration" (accompanied by a loud zap). Calvin makes his first foray into the world of transmogrification when he temporarily turns himself into a tiger, but he finds the experience disappointing. Calvin re-uses some of this technology when he cleverly converts an ordinary water gun into a portable transmogrifier gun, a device which saves his life when he finds himself falling from high altitude. (Although he yells "I'm safe!" and is consequently turned into a safe, he rectifies this mistake by turning himself into a light particle and "zips home instantaneously".)

A Duplicator is crafted by turning the box on its side. Whatever is put in the box will be duplicated with a boink sound (hence the book title, Scientific Progress Goes Boink). Calvin envisions having a small team of duplicate Calvins whom he could send off to school, so he could go about his own business during school days. However, the new Calvins prove to be exact replicas, with the same reluctance to go to school, and thus become difficult to control. Calvin later adds an "Ethicator" switch to his duplicator, allowing a duplicate to be designated "good" or "evil," since he believes that a duplicate of his well-buried "good side" could cause no harm. This experiment is successful at first, with the "good" duplicate willingly doing Calvin's homework and going to school. The "good" duplicate crosses the line when he starts courting Susie, and Calvin eventually destroys it.

The time machine is built by flipping the transmogrifier back so that the opening faced upwards again. One uses it by donning a pair of goggles (in order to "contend with vortexes and light speeds") and climbing into the vehicle. Facing the front makes the machine go forward in time, and facing backwards makes it travel into the past. Calvin and Hobbes discover these time travel mechanics when they attempt to go into the future in order to bring back a few futuristic inventions and patent them in the present, securing a fortune for themselves. However, they face the wrong way and end up in the Jurassic period, bringing them face-to-face with a very large dinosaur. In another storyline Calvin tries to solve his homework by traveling to the future, planning to pick the finished work up from his future self, "8:30 Calvin". Not surprisingly, Calvin's plan fails to work as he intended. In the end, Hobbes (with the "8:30 Hobbes"'s help) ends up writing about a kid that tries to solve his homework by planning to pick the finished work up from his future self.

Briefly, the cardboard box is used for Calvin's costume of "The World's Most Powerful Computer," in which Calvin walks around with the box over his head and a mechanical face sketched onto the surface of the box. This is only used two times throughout the entire strip.

Calvin's last cardboard box invention is the Cerebral Brain Enhance-o-tron, which combined with a colander creates a "thinking cap," a garment which enhances his mental prowess (inadvertently causing his head to swell in addition). Upon activation, this machine goes brzap. Like his other inventions, the Cerebral Enhance-o-tron fails to change his life; even with his "cerebral augmentation," he is unable to write a school report up to Miss Wormwood's standards.

Most of the other characters do not see his inventions as "real." For example, when Calvin transmogrifies himself into an owl or a tiger, his parents do not observe the transformation; only he and Hobbes see the change, and when they traveled back in time to photograph dinosaurs, Calvin's dad told Calvin that the dinosaurs in the photos looked too "plastic". However, they do seem to see Calvin's duplicates as Calvin's mom recalls sending Calvin out of the kitchen, to his room (to which the Calvin she saw replied "I'm not Calvin, I'm his duplicate!") even though Calvin was outside at the time. This is a similar dilemma to that of Hobbes' existence (see the Hobbes article).

Wagon and sled

Calvin and Hobbes frequently ride downhill in a wagon, sled, or toboggan (depending on the season) and ponder the meaning of life, death, God, and a variety of other weighty subjects as they hurtle downhill. The wagon and sled were conceived because of Bill Watterson's aversion to "talking heads" comic strips, as a way of making them visually exciting. The course of the vehicle and the obstacles that the characters negotiate as they travel also frequently serve as metaphors for and parallel to the subject of conversation (life becomes a blur, Calvin says as he speeds along), and the rides almost always end in a spectacular crash.

The wagon temporarily served as a spacecraft when Calvin and Hobbes realized that the human race was laying waste to Earth by polluting it. They decided to go live on Mars, but returned soon after when they realized that the native Martians (or, "weirdos from another planet") were terrified of Earthlings. This may have been a case of rumor preceding them; the prospect of terrestrial life polluting Mars as well as Earth was a bleak one. Although this particular wagon ride did not end in a crash, it once again served as an outlet for a subject matter of importance.

Snowballs and snowmen

During winter, Calvin often engages in snowball fights (which he almost always loses), usually throwing them at Susie but always resulting in Calvin getting buried in the snow as retaliation. He sometimes teams up with Hobbes for snowball fights, but Calvin can't seem to resist also sneaking up on Hobbes, who always seems to get the drop on him instead.

Calvin also builds snowmen; but these are usually grotesque, monstrous deformed creatures (e.g., two-headed snowmen, a snow monster with tentacles devouring a bunch of snowmen, a snowman who grabs another snowman's head and uses it as a bowling ball, a snowman who scoops snow cones out of the back of a dead snowman, snowmen getting hanged, a buried giant snow monster destroying other snow men or holding their heads in its hands, and a prostrate snowman seemingly beneath the parked family car, surrounded by a host of worried "snow-onlookers", etc.) In one storyline, Calvin builds a snowman and brings it to life using the power "invested in him by the mighty and awful snow demons". The snowman immediately turns evil (reminiscent of the film Frankenstein) and becomes a "deranged mutant killer monster snow goon" by giving itself two heads and three arms. The snow goon then makes copies of itself which Calvin eventually defeats. However, Calvin was caught by his parents and had to explain why he was outside when he should've been asleep (which wasn't successful).

Calvin, unlike Hobbes, thinks of snowmen as a fine art. Bill Watterson has said that this is to parody art's "pretentious blowhards".[17] Once, out of ideas, Calvin signed the snow-covered landscape with a stick and declared all the world's snow as his own work of art, offering to sell it to Hobbes for a million dollars. Hobbes mellowly responds, "Sorry, it doesn't match my furniture," and walks away, leaving Calvin to contemplate, "The problem with being avant-garde is knowing who's putting on who."

Dinosaurs

Calvin enjoys dinosaurs very much; they are perhaps the only subject which he regularly studies of his own free will. Carnivorous dinosaurs also frequently serve as Calvin's alter-egos; for instance, he will often imagine himself as a Tyrannosaurus rex on the hunt, usually with Susie Derkins as the "peaceful" herbivore. Another strip features Tyrannosaurus Rex's flying F-14 jets pursuing peaceful herbivores. Once Calvin was an Allosaurus, and Moe was an Ultrasaurus. Moe was at the drinking fountain and Calvin wanted to push him off, but the Allosaurus was of course no match for the Ultrasaurus; when he tried to attack it, he quickly shied off. Another Sunday strip involved Calvin, a Tyrannosaurus, attacking Susie, a Hadrosaurus, with a snowball. The Tyrannosaurus was quickly chased away, prompting Calvin to throw away his dinosaur books. Calvin once claimed he had discovered a new species of theropod, a Calvinosaurus, a predator so large that it "could devour a whole sauropod with one bite." When the film Jurassic Park came out in 1993, Bill Watterson reduced the portrayals of dinosaurs in his strips because he did not want Calvin's dinosaurs to seem "bland" in comparison to the movie.

Calvinball

Calvinball is a game played almost exclusively by Calvin and Hobbes as a rebellion against organized team sports (like baseball), although the babysitter Rosalyn plays on one occasion. Calvinball is played with whatever implements are available, often a volleyball (called the "Calvinball" itself) and a pair of wickets, and the rules are invented as the game goes along. The two consistent rules are 1.) that the rules can never be the same twice (which in itself is a self-denying paradox), and 2.) that everyone who plays Calvinball must wear a mask. Either player may change any rule at any time (with the exception of those rules stated above). Scoring is also entirely arbitrary: Hobbes has reported scores of "Q to 12" and "oogy to boogy." Calvinball is essentially a game of wits and creativity, rather than purely physical feats, and in this Hobbes is typically more successful than Calvin himself.

The reader first encounters the game after Calvin's horrible experience with school baseball. He registers to play baseball in order to avoid being teased by the other boys. While daydreaming in the outfield, he misses the switch and ends up making an out against his own team. His classmates mock him and, when he decides to walk away, his coach calls him a "quitter." That Saturday, Calvin and Hobbes play Calvinball for apparently the first time, a game far removed from any organized sport. Even Calvin and Hobbes's own attempts to play organized sports between themselves usually deteriorate into Calvinball, as they end up inventing increasingly bizarre rules that cause whatever sport they were initially playing to spiral out of control.

In the Tenth Anniversary Book, Watterson states that the greatest number of questions he receives concern Calvinball and how to play it. He then answers the question once and for all: "People have asked how to play Calvinball. It's simple: You make up the rules as you go along."

School and homework

Calvin hates school and its attendant early-morning risings, irate teachers, homework, and fellow students. Often his mother has to force the unwilling Calvin to catch the school bus. Occasionally he manages to avoid the bus, and his mother has to chase him down and force him to board or drive him to school. Calvin often waits for the bus with Hobbes and explains why an intelligent boy like himself does not need school. While at school, he commonly visualizes the building as a hostile planet and his teacher and principal as vicious aliens. Calvin usually lacks the company of Hobbes at school. Sometimes Hobbes does his homework and reading while Calvin watches TV or reads comic books. In general, Calvin is depicted as a lazy student who is unable to concentrate in class, has difficulty interacting with other students, and struggles with homework. On occasion, he gets good marks and positive feedback for work, but these are usually short-lived victories.

Also on occasion, Calvin's inability to concentrate in class is compromised by inserting the class subject into his daydream, causing him to get the right answer. This includes spelling "disaster" while crash-landing on an alien world and blurting out the right answer at a completely random moment (from his point of view). Calvin also attempts to escape his classroom rather often, these endeavors are sometimes successful, but most often futile.

It should be noted that his dislike of school does not necessarily mean that Calvin is unintelligent; the strip often depicts him as being very smart, in fact, with unusual knowledge of philosophy and odd vocabulary. Rather, Calvin seems to dislike school because of its rules and forced learning of things which he is not necessarily interested in. In one strip, Calvin's father asks why he doesn't try harder at school, considering how much he loves to learn about subjects like dinosaurs; Calvin simply replies that they don't learn about dinosaurs in school. His inability to concentrate is portrayed as more due to his active imagination than to any mental handicap. In one Sunday edition, he is called to the board to do an addition problem, but instead delivers an epic poem in several stanzas that detail his kidnapping by aliens who have "mechanic'ly removed" all his mathematical knowledge via a "brain-draining operation". One stanza:

- Even then I tried to fight:

- And though my enemies were many

- I poked them in their compound eyes

- And pulled on their antennae.

The Noodle Incident

The Noodle Incident was an event alluded to in many Calvin and Hobbes strips. Although the event was never shown "on camera" and the characters never discussed the exact details, the many references made to it reveal some information. For one, we can be sure that it happened in school, as Calvin was worried about whether Miss Wormwood had told his mom about it. Watterson frequently alluded to the Noodle Incident in comics around Christmas time. Hobbes typically mentions the incident when Calvin talks about Santa Claus's view of his behavior. When asked about the incident Calvin would usually answer, very loudly and defensively, "No one can prove I did that!!" Calvin claims he was framed for whatever the incident actually was.

In The Calvin and Hobbes Tenth Aniversary Book, Watterson said that the Noodle Incident was a theme, much like Calvin's favorite bedtime story Hamster Huey and the Gooey Kablooie, that he preferred to leave to the reader's imagination.

Calvin and Hobbes books

- For the complete list of books, see List of Calvin and Hobbes books.

There are eighteen Calvin and Hobbes books, published from 1987 to 2005. These include eleven collections, which form a complete archive of the newspaper strips, except for a single daily strip from November 28, 1985. (The collections do contain a strip for this date, but it is not the same strip that appeared in some newspapers. The alternate strip, a joke about Hobbes taking a bath in the washing machine, has circulated around the Internet.) "Treasuries" usually combine the two preceding collections with bonus material, and include color reprints of Sunday comics.

A complete collection of Calvin and Hobbes strips, in three hardcover volumes, with a total 1440 pages, was released on October 4, 2005, by Andrews McMeel Publishing. It also includes color prints of the art used on paperback covers, the Treasuries' extra illustrated stories and poems, and a new introduction by Bill Watterson, who is now happily teaching himself to paint. It is notable, however, that the alternate 1985 strip is still omitted, and two other strips (January 7, 1987, and November 25, 1988) have altered dialogue.

To celebrate the release, Calvin and Hobbes reruns were made available to newspapers from Sunday, September 4, 2005, through Saturday, December 31, 2005, and Bill Watterson answered a select dozen questions submitted by readers.[20][21] Like current contemporary strips, weekday Calvin and Hobbes strips now appear in color print when available, instead of black and white as in their first run.

Early books were printed in smaller format in black and white that were later reproduced in twos in color in the "Treasuries" (Essential, Authoritative, and Indispensable) — except for the contents of Attack of the Deranged Mutant Killer Monster Snow Goons. Those Sunday strips were never reprinted in color until the Complete collection was finally published in 2005. Every book since Snow Goons has been printed in a larger format with Sundays in color and weekday and Saturday strips larger than they appeared in most newspapers.

Remaining books do contain some additional content; for instance, The Calvin and Hobbes Lazy Sunday Book contains a long watercolor Spaceman Spiff epic not seen elsewhere until Complete, and The Calvin and Hobbes Tenth Anniversary Book contains much original commentary from Watterson. Calvin and Hobbes: Sunday Pages 1985-1995 contains 36 Sunday strips in color alongside Watterson's original sketches, prepared for an exhibition at The Ohio State University Cartoon Research Library.

An officially licensed children's textbook entitled Teaching with Calvin and Hobbes was published as part of a limited single print-run in 1993.[5] The book includes various Calvin and Hobbes strips together with lessons and questions to follow, such as "What do you think the principal meant when he said they had quite a file on Calvin?" (p108).

References

- ^ "Andrews McMeel Press Release". Retrieved 2006-05-03.

- ^ David Astor (November 4, 1989). "Watterson and Walker Differ On Comics: "Calvin and Hobbes" creator criticizes today's cartooning while "Beetle Bailey"/"Hi and Lois" creator defends it at meeting". Editor and Publisher. p. 78.

- ^ a b c Paul Dean (May 26, 1987). "Calvin and Hobbes Creator Draws On the Simple Life". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "A Concise Guide To All Legitimate (and some not-so-legitimate) Merchandise". Retrieved 2006-03-16.

- ^ a b Holmen, Linda (1993). Teaching with Calvin and Hobbes. Playground. ISBN 1878849158.

- ^ Watterson, Bill (1990). "Some thoughts on the real world by one who glimpsed it and fled". Retrieved 2006-03-16.

- ^ Neely Tucker (4 October 2005). "The Tiger Strikes Again". Washington Post. p. C01.

- ^ a b c d Andrew Christie (January 1987). "An Interview With Bill Watterson : The creator of Calvin and Hobbes on cartooning, syndicates, Garfield, Charles Schulz, and editors". Honk magazine.

- ^ "NCS Reuben Award winners (1975-present)". National Cartoonists Society. Retrieved July 12.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "Andrews McMeel Press Release". Retrieved 2006-05-03.

- ^ "Newspaper cutout of the last Calvin and Hobbes strip". Retrieved 2006-03-19.

- ^ a b c d

Richard Samuel West (February 1989). "Interview: Bill Watterson". Comics Journal (127).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ David Astor (December 3, 1988). "Watterson Knocks the Shrinking of Comics". Editor and Publisher. p. 40.

- ^ Watterson, Bill (1989). "The Cheapening of Comics". PlanetCartoonist. Retrieved 2006-03-16.

- ^ Watterson, Bill (2001). Calvin and Hobbes: Sunday Pages 1985-1995. p. 15. ISBN 0740721356.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b "Fans From Around the World Interview Bill Watterson". Andrews McMeel. 2005. Retrieved 2006-03-16.

- ^ a b c d e Watterson, Bill (1995). The Calvin and Hobbes Tenth Anniversary Book. Andrews McMeel. ISBN 0-836-20438-7.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Williams, Gene (1987). Watterson: Calvin's other alter ego.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Watterson, Bill (1993). The Days are Just Packed. Andrews McMeel. ISBN 0-836-21769-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Calvin and Hobbes - We're Back!". Universal Press Syndicate. September 4, 2005. Retrieved 2006-03-17.

- ^ David Astor (May 20, 2005). "Calvin and Hobbes Returning to Newspapers — Sort Of". Editor and Publisher.

External links

Official websites

- "Official Calvin and Hobbes site". Retrieved 2006-06-02.

- "Publisher Andrews McMeel's official Calvin and Hobbes site". Retrieved 2006-03-17.

Fan websites

- Calvin and Hobbes Hideout URL accessed March 31, 2006

- Simply Calvin and Hobbes URL accessed March 18, 2006

- Calvin and Hobbes: Magic on Paper URL accessed March 29, 2006

- The Calvin and Hobbes Album URL accessed June 3, 2006

- Michael's Calvin and Hobbes Site URL accessed June 3, 2006

Articles/Misc.

- Chris Suellentrop (November 7, 2005). "The last great newspaper comic strip". Slate magazine.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - "Missing! Calvin and Hobbes creator Bill Watterson". Cleveland Scene. November 26, 2003.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Neely Tucker (October 4, 2005). "The Tiger Strikes Again". The Washington Post.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - "Radio show in which fans of the comic strip express their views about the ending of Calvin and Hobbes" (mp3). CBC Canada. 1995.

- Template:Dmoz

- Galvin P. Chow (March 11, 2001). "Metaphilm article relating Fight Club to Calvin and Hobbes". Metaphilm.com.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)